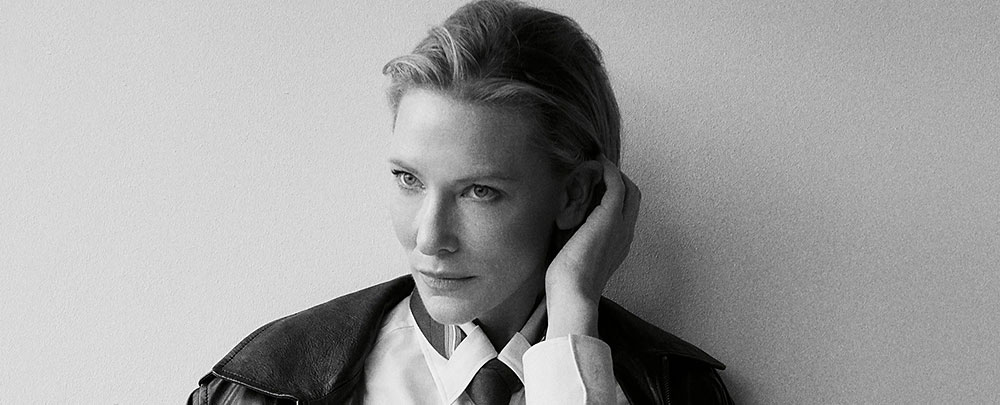

Cate Blanchett is on the cover of the new T Magazine’s issue! The magazine will be on sale from August 23rd!

On Edge

Cate Blanchett is known for playing women who are just barely holding it together. In life, she’s firmly in control.It was Cate Blanchett’s second time climbing the Sydney Harbour Bridge. She couldn’t really say why she wanted to do it, or what it is about heights that appeals to her. She has no interest in skydiving or bungee jumping or parachuting. She’s not especially sporty or athletic. It’s not thrills she likes; it’s control. She once drove her children to the edge of Mount Yasur, an active volcano on the island of Tanna.

“It was fantastic to be able to say, I’m deciding to do this,” she said. “I’m deciding the level of safety for my children without someone telling me what to do.”

She was wearing a baggy blue and gray flight suit — baggy enough to slip over a pair of loose leather pants and leave room to spare. It wasn’t that she looked good in the suit so much as she made the suit irrelevant. A strap hanging off the belt connected to a cable that ran inside the thousand feet of stairs, catwalks and steel beams of the bridge.

“I love to climb high things,” she said. We were standing on the midpoint of the exterior archway, with a sniper’s vantage on the opera house. She wanted to go even higher, up a short ladder that led to a rotating red light, but Nick, the climb guide, said it wasn’t allowed.

Nick had seen a fur seal in the harbor on his morning run, and Blanchett wanted to know all about it: how big it was, and if it was furry. She had questions about Shark Island. She pointed to Cockatoo Island. “It was a prison for convicts and then it was a reform school for wayward girls, so you can imagine what goes on there.” She pointed and pointed — to ports, to mountains, to secluded spots of green. To mangrove beaches where you can wander and never meet another soul. “People go to the usual places,” she lamented. Then she laughed and her voice dropped into sarcasm. “Like this, for instance. It’s the insider’s Sydney you’re experiencing today.”

Blanchett had descended to the interior archway and was deploring the gentrification of Brooklyn when a line of identically blue and gray flight-suited figures above began clamoring for attention. They were leaning over the bars, whooping and clapping.

“They’re waving at you,” I said.

“I don’t know,” she said.

“It’s like when you’re on a boat,” Nick said helpfully.

Blanchett agreed that this situation was like when you’re on a boat. She half-waved at the admirers, a motion at once friendly and plausibly deniable, and continued the descent. She paused on a slip of the bridge that sits between two sets of train tracks to remember when Kevin Spacey pushed somebody — she couldn’t remember who — in front of a train on “House of Cards.” She wished that a train would pass us — better, that two trains would pass us, in opposite directions, at the same time.

“What if it went, ‘Choom! Choom!’?” she said. “We could have the double action!”

Then she laughed. “Oh my god, I’m getting hysterical.” Through the open steps the water of the harbor glittered green and jewel-like below.

“Transport!” she yelled giddily and threw her arms in the air. A train sped by, granting half her wish. “It’s amazing.”

The vibrations from the train faded into the noise of automobile traffic as we proceeded single-file toward the climb base. Blanchett was shouting about Chekhov. She especially likes the way he does silences. Chekhov’s silences, she said, are like the moments at a dinner party when everyone stops talking — “stupid silences,” the Hungarian director Tamas Ascher calls them. It’s not that people are thinking of something to say, or motivated by some particular desire. They’re just — there. Just — between.

Blanchett, who is 46, is currently starring in her husband Andrew Upton’s adaptation of Chekhov’s “The Present” at the Sydney Theatre Company. She and Upton moved home to Australia in 2008 to take over the company as co-artistic directors. (Her first-ever professional acting job was at the Sydney Theatre, as an understudy in Caryl Churchill’s “Top Girls.”) They live with their four children — biological sons Roman, Dash and Iggy, and newly adopted baby Edith, from America — in a suburb of Sydney. Blanchett officially stepped down as co-director of the theater in 2013, but Upton will run the company through the end of the year, and in practice she remains involved; as she put it, “We do everything together.”

Back at the base, Blanchett signed photos for the Sydney Harbour Bridge Climb’s celebrity wall and we walked to a nearby restaurant for dumplings and salad. She sat with her back to the window and removed the sunglasses that had obscured half her face all morning. A fine wrinkle cut a shallow line into the side of her jaw, which somehow made her look younger.

She explained that running the theater company had been transformative. It wasn’t only that she shepherded productions she was proud of, including “The Secret River,” based on a novel about Australia’s racial history; “The Long Way Home,” which was performed by servicemen returned from Iraq and Afghanistan; and Botho Strauss’s forgotten “Gross und Klein,” which afforded her the “personally liberating” experience of working with director Benedict Andrews. She also became an advocate for the theater community as a whole. She had to think bigger than just her own company: A healthy “theatrical ecology” means that lots of companies are thriving and everyone’s audiences are growing. This required her to take the microphone, come out of her shell a bit.

“I learned to not feel responsible to other people’s perceptions of who you are,” she said. “I suppose I’ve gone through a process of maturation, in a way, because running the company is a public position.”

I said that I would have thought that being a Hollywood actress would have felt like a public position. Blanchett has appeared in 48 feature films. My in-flight entertainment system had offered seven of them.

She frowned, and her eyes clouded. She did not like the phrase “Hollywood actress.” “That’s what they say about you when they want to insult you,” she said.

She ignores the trappings of celebrity as best she can, and advises younger actresses not to go on social media, which “creates a culture of self-consciousness.” She is drawn to figures who “have utterly shedded self-consciousness but are completely masters of their technique, like Louise Bourgeois and Georgia O’Keeffe. They’ve got that raw, wrought intelligence.” She also admires Pina Bausch. “If I had my time over, I would have loved to have been in her company,” she said. “She was an incredible, incredible creature — fierce.”

She ran her hand across her hair smoothly, turning in profile with her chin slightly angled down. It’s a gesture she makes repeatedly in “Blue Jasmine” — a moment of putting yourself back together, preparing to meet another.

Consider how many of Blanchett’s most notable characters have struggled with these very issues — the burdens of recognition and fame, or the shame of being watched or hunted. Bob Dylan, Katharine Hepburn, Jasmine, Queen Elizabeth, even the art teacher who sleeps with the high school student in “Notes on a Scandal” — they are all tortured by their awareness of other people’s perceptions, and, in the process, lose their composure. Blanchett is especially good at performing this state of just-barely-holding-it-together, that veneer that cracks to reveal an unhinged or demented person inside. Yet her performances grant refinement to the most degraded or distressing situations. She telegraphs something regal and elite; even when her characters are not financially well-to-do, they are never “ordinary.”

This winter she will add another elegant woman under surveillance to her repertoire of roles, playing the title part in Todd Haynes’s beautiful new film “Carol.” (She is also starring in “Truth,” as the CBS producer who approved the “Sixty Minutes” investigation into George W. Bush’s National Guard service.) “Carol” is adapted from “The Price of Salt,” the 1952 Patricia Highsmith novel widely regarded as the first lesbian novel with a happy ending (i.e., nobody dies). The plot concerns an affair between young, unsophisticated ingénue Therese (Rooney Mara) and Carol, a glamorous older woman. Readers of the novel will know the famous road trip sequence — it’s said that Nabokov copied it for “Lolita” — in which the lovers are pursued by a private detective hired by Carol’s ex-husband to build a child custody case against her.

Blanchett has admired Haynes since they first worked together on “I’m Not There.” She compares him to Klausner, a character in the Roald Dahl story “The Sound Machine,” who can hear the clouds moving in the sky and the grass screaming under the blades of a lawnmower. “Todd is a good person, and a wild person, and a responsible person,” she said. “You could probably tell him anything.”

As for Highsmith, she first discovered her novels in the late 1990s, when she was cast in “The Talented Mr. Ripley.”

“She writes so fearlessly — and often ambiguously, but often ferociously — about human relationships and the human heart,” Blanchett said. “I always have this terrible sense of foreboding, like a thrilling sense of foreboding, like something terrible is going to unfold. Like you never feel safe.”

The key to suspense, of course, is control. The knowledge that someone is in control makes danger pleasurable. So much of Blanchett’s life and work revolves around a very careful calibration of control and chaos. Control is what makes ferocity effective rather than only cruel. Control is what makes it fun to visit a volcano. As for her occasional, well-documented eruptions — her facetious comment to a reporter who queried her sexuality, her punch-drunk interview on a “Cinderella” junket in the spring — they would mean something different were it not for their divergence from her usual poise.

The conversation returned to the peculiar problem of theater acting: how to be in and out of the flow of the moment, how to practice and prepare and bind together all the “Eureka moments” that recapture the spark of a first reading. The way she explained it, when a scene is working, the actors are equally aware of the person unwrapping a snack in row G and the other bodies on the stage.

She hates monologue. For her, everything interesting is in collaboration. “That’s the dangerous side,” she said. “You really don’t know where you’re going to go.”

via T Magazine

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?)

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?) The Seagull (2025)

The Seagull (2025) Bozo Over Roses (2025)

Bozo Over Roses (2025) Black Bag (2025)

Black Bag (2025)  Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)

Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)  Disclaimer (2024)

Disclaimer (2024)  Rumours (2024)

Rumours (2024)  Borderlands (2024)

Borderlands (2024)  The New Boy (2023)

The New Boy (2023)