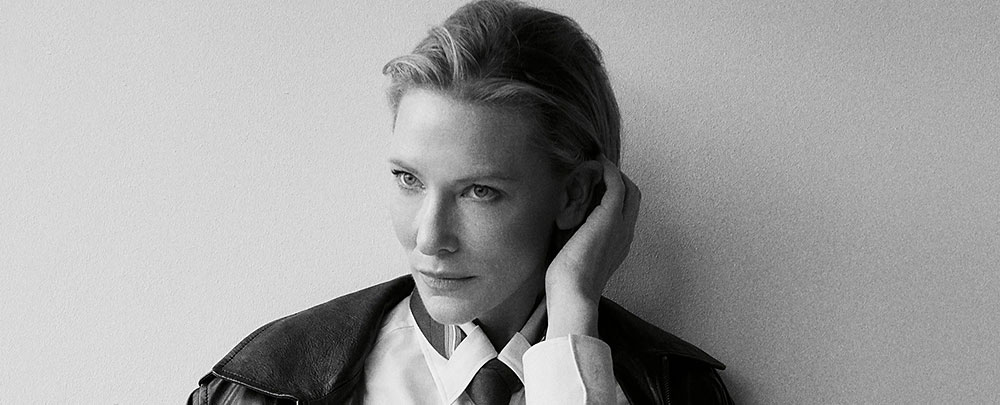

A new interview with the Huffington Post!

When offered 10 minutes of face time with Cate Blanchett, one must decide which of the many possible questions are worthy of asking. So I did, of course, but shortly before it was my turn to sit down with her, a publicist informed me that, sorry, the junket was running behind and we’d only have five minutes to talk. Then I felt frazzled because I didn’t cull my questions to just a few moments’ worth, and I really wanted to talk to her about how that morning I’d seen a great movie she wasn’t even in, because she knows the director and lead star. Things got even more complicated when the publicist tried to cut us off after less than three minutes. But God save the queen, because Blanchett begged for a few more with me so we could actually get to a meaningful place in the conversation.

In actuality, there’s no better time to have a few minutes with Cate Blanchett. As her narrative within the current Oscar race goes, the two-time winner will compete against herself in the Best Actress derby. She could be nominated for “Truth,” in which she plays Mary Mapes, the venerated “60 Minutes” producer responsible for the widely criticized 2004 Bush report that led to Dan Rather’s (Robert Redford) downfall. Or she could be nominated for “Carol,” the festival favorite about a young retail clerk (Rooney Mara) who falls for an older, married woman in 1950s New York. She won’t get both nods, however, because performers cannot occupy two slots in the same Oscar category. (“I just hope they can both find their audience,” she demurred when Indiewire’s Kate Erbland asked about her dual awards odds.) During my hurried few minutes with Blanchett, I wanted to touch on both roles, in case I don’t get to talk to her again when “Carol” opens next month. But first, about that movie she wasn’t in …

It’s funny that I’m talking to you today because I just saw “Brooklyn” this morning.

Oh, isn’t it extraordinary? I just finished working with John Crowley — he directed a play I was in.

And I know he was supposed to direct “Carol” at one point, too.

Yeah, he was the one who brought the script to me initially and then he wasn’t available. Then Todd Haynes did it, which was extraordinary. But he’s a wonderful director. “Brooklyn” is beautiful. It’s one of those really slow-burn films, and when you hear the bones of the story, you think, “OK, yeah, sure.” But then what he and Saoirse Ronan and the rest of the cast did — that extraordinary boy, is it Emory?

Emory Cohen, the one who plays her boyfriend?

Yes! Extraordinary. But it’s so painful. I watched it with my husband and it reminds you of that first moment where you ever fell in love and the fact that some people have fortunate lives and some people have unfortunate lives, and about guilt and responsibility. I loved it. And Saoirse is extraordinary. She’s extroarindary. But Todd has made a beautiful film with “Carol.”

In thinking about “Truth,” what changed in your perception of Mary Mapes between reading the script and meeting her?

You know, I knew nothing about Mary. I had obviously seen the Abu Ghraib story and then found out that she’s produced the Bush Guard story, which I thought was a very interesting counterpoint to all of that John Kerry Swift Boat stuff that was going on, except that one story floated and one story sank. But I didn’t know anything about the personal and professional fallout from the story, so the script was revelatory to me in that way. Of course, I started looking her up and trying to find anything about her on the Internet because she was behind the camera, and I saw a lot of interviews she’d given post the story breaking. She was clearly in lockdown and when I met her I found it very difficult to reconcile that Mary to this incredibly vivacious, vital, vibrant, hilarious, front-footed go-getter. I thought somewhere between the two lies Mary. But she was very generous, very self-deprecating, very wry and very, very passionate and full of heart.

[At this point, the publicist attempted to usher me out. “Can we have two more minutes?” Blanchett pleaded. “Because otherwise we haven’t even said anything about the film. Two more minutes!”]

How easy is it to transition from the outsized emotions your characters showcase in “Truth” and “Cinderella” to the quiet subtlety of “Carol”?

I think the demands of “Carol” come from Carol being such an enigmatic character. The novel is told completely from [her romantic interest’s] perspective, so Carol is a subjective creation. As we fall in love with people, it’s always from a subjective point of view. You know, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. I thought what Phyllis Nagy did with the script so beautifully is she realized a three-dimensionality and an objectivity to Carol, and that’s what Todd did with the filmmaking. The challenge was to play someone who was real and three-dimensional but continually enigmatic and full of ambiguity. Her sexuality had no name and Carol didn’t fit into a particular subculture, so that visual niche expression of that was not an easy thing to find.

That comes across in how stilted a lot of their interactions are. The magic is in how the look at each other. Their feelings were so foreign that they didn’t even know how to communicate, really.

Well, it doesn’t have a name.

In both movies, you have moving telephone scenes. In “Truth,” it’s with Mary’s very difficult father, and in “Carol,” it’s during the vital stages of Carol’s new romance, which is complicated by the fact that she has a husband at home.

Oh, yes! I hadn’t thought about that. Well, I suppose both films deal with people who are outsiders, in very, very different terrain. I hadn’t thought about this, actually, but Mary was an outsider — she lived in Texas, which she describes as the intergalactic capital of “shit happens.” But she’s an outsider because most of that journalism she was dealing with on “60 Minutes” was based on the East Coast and she was silenced by CBS. She was told not to speak to any press, so she was isolated. And Carol, because of her situation and the very subtle but absolute contract that is made between she and Harge [her husband], is completely cut off — not only from Therese, but sort of from her own emotion. So I think the telephone becomes a conduit for both of those characters.

When you’re filming those scenes, how easy is it to process not hearing the voice on the receiving end?

Well, Rooney is amazingly generous, as is Bob Redford, as is Dennis Quaid. When Dennis was doing his shots at night in the Dallas bureau, I just said to the first AD, “Call me. I’ll be at home with the kids.” So I said, “Sorry! Shut up, I’m going to the dining room,” and I would be there on the call. It’s really important not to act into a void, so Rooney would be there on the end of the call for me, as I was there on the end of the call for her.

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?)

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?) The Seagull (2025)

The Seagull (2025) Bozo Over Roses (2025)

Bozo Over Roses (2025) Black Bag (2025)

Black Bag (2025)  Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)

Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)  Disclaimer (2024)

Disclaimer (2024)  Rumours (2024)

Rumours (2024)  Borderlands (2024)

Borderlands (2024)  The New Boy (2023)

The New Boy (2023)