Happy Sunday, everyone!

A new interview with Cate has been released. This is a Google translated interview from Spanish to English.

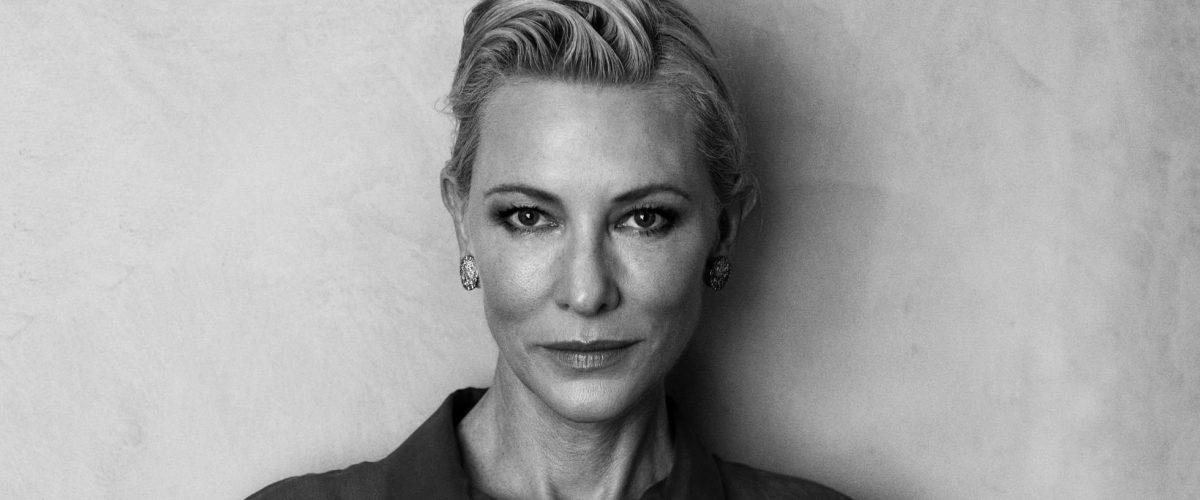

Cate Blanchett: “I spend most of my time being someone else. I want to spend more time being myself.”

Other than her two Oscars, Cate has added in recent weeks from Europe the first International Goya and a César for her entire career. Actress, producer, and farmer, the versatile Australian performer, also an ambassador for Armani fragrances, she confesses that with age she feels more limitations when it comes to acting. She laments that she is sometimes still the only woman on a shoot and she fears that the platforms will become monopolies.

Cate Blanchett (Melbourne, 52 years old) thinks there are too many awards. And she knows what she’s talking about. Because she has almost all of them: two Oscars, three Baftas, three Golden Globes and three from the Screen Actors Guild. As if they weren’t enough, she has now embarked on the conquest of Europe. She has just received an Honorary César in Paris and a month ago she picked up the International Goya from Pedro Almodóvar, with whom she is going to shoot the first film in English by the Spanish director, A Manual for Cleaning Women. She welcomes us in Valencia, hours before hugging him and thanking him for a recognition that serves to strengthen ties with the Latin film industry. She wears trainers and a metallic pink suit by Giorgio Armani, the firm whose line of fragrances is an ambassador. Under the jacket, the skin, and around her neck, several golden chains with padlocks and snake heads that she plays with as she speaks. After premiering Nightmare Alley last February under the direction of Guillermo del Toro and dazzling the world with her false teeth in Don’t Look Up, she says she wants to spend more time playing herself. Normal: the character is exciting.

In an interview Julia Roberts did for Interview Magazine, you said that as you gets older, you find acting more and more humiliating.

It gets more difficult. Why? I think that when you work in the artistic field — also if you are, for example, a writer—, this field becomes more and more entangled in your life. I spend most of my time being someone else, and I think I want to spend more time being myself. Also, as an actor you are very exposed. I do not know how to explain it. Six years ago [photographer and artist] Cindy Sherman started using digital effects to create her works [in which she often appears]. And people threw their hands in their heads because she had always used prosthetics and had worked her body as if it were a malleable object. She simply explained that she had reached an age where she was less malleable. And that she had to resort to digital technology to maintain the same skill.

Is it the same as an actor?

You feel a bit the same, that your palette is getting smaller and smaller. But the truth is that I am not very interested in digital advances. What I like are magic tricks, I still scream when someone does one in front of me. Because with magic you become an accomplice: you know you are being deceived, but in the digital universe you don’t know what is real and what isn’t. It’s like when you see Gary Oldman without prosthetics or digital treatment, the interpretation of him is something that he builds from the inside and you believe it. He is really inspiring. I’ve worked with digital retouching on The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and, yes, it can be liberating, but in the end, as you get older, you face more and more of your limitations, and that’s humbling.

Is the film industry easier for women now than when you started?

If we keep talking about it, the problem still exists. But we have to keep talking and working on it until it is no longer a topic of conversation. Sometimes I keep walking on set and there are 30 men and I’m the only woman, and I think, “This is so out of sync with what’s going on in society. How is it possible for us to connect with the audience like this?” When you’re in a predominantly male or white work environment, it feels old-fashioned and you feel like it’s also starting to be irrelevant. I think there has been a big change. But you have to stand firm and understand that changes are very fragile, as is democracy. So you have to persevere.

You were artistic director of the Sydney Theater Company. Has that experience influenced your way of understanding her work as an actress?

We were not only artistic directors [and her husband, screenwriter and playwright Andrew Upton], but also CEO, so we were responsible for the financial and creative health of the company. And many times these two aspects are conceived as mutually exclusive. But they don’t have to be: throughout my career I’ve worked with producers who are amazing at keeping finances in order while also helping with creative decisions.

Is that producer profile in danger of extinction?

Yes, unfortunately, because it is something I aspire to. It’s not all about being in front of the camera. I don’t feel obligated. No longer. I’ve already done it. I’ve bored the audience enough already. I do not need it. No more.

Throughout your career you have played everything from action characters to femme fatales, through comedic roles or even men, such as Bob Dylan. How do you choose your characters? Is there any kind of woman you would never play?

Many decisions are based on instinct and timing. I have a wonderful and great life, with a lot of commitments and things that interest me, starting with my farm, with my sheep, my pigs, my cows, and with my children, of course. So sometimes not all projects fit into my schedule. But nothing happens. There is no need to bleed for it. You have to let them go. It’s one of the best things the film industry has taught me.

The fact that?

You make a film and you let it go because after your work comes post-production work and finally, if you’re lucky, it reaches the public. And by that time you will have already done one or two other things. And that film happens to become a kind of second cousin. And then, hopefully, you can see it again with fresh eyes and appreciate it.

What do you expect now from A Manual for Cleaning Women, your project with Almodóvar?

We had talked many times about working together, but it was never the right time. He is a man of incredible taste and insight. He is very precise and, like his films, very free. We are very aligned and excited about the project. I love it because he works with his heart and with his hands. And with his head, of course. He is a person very connected with what happens in the world, but at the same time someone who follows his own path. So I think this project will be unique. His work has a clearly Spanish framework, but it has always transcended and has been recognized internationally because it connects very well with American concerns: the family, being outside the majority culture, being an outcast. I think it’s going to be a fascinating journey in search of that hybrid between the American and the Latin experience.

You have a master’s degree in that Latino perspective. You have worked with Alejandro Cuarón, Guillermo del Toro and now Almodóvar. Is there something that differentiates Latino directors from the rest?

They all have incredible hearts and a certain brutality, but not in the bad sense of the word. I mean they don’t run away from things that others prefer not to name. And they are profoundly plastic artists. His intellectual pursuits are very sumptuous to digest visually. Latino and Australian directors have a very special, unique vision of the world, and that is why they have more and more weight in the US film industry.

I said before that Almodóvar was a very precise director. Is he the kind of director you like to work with, someone who gives a lot of directions and controls every detail?

I think the project is what dictates how you have to work. For me, the perfect thing is to have a clear line of communication with the director based on trust, because there are moments in the shoot when you have to say that something is rubbish, and you have to know that it comes and is said from respect. Rehearsals and filming are not always friendly. They are not disrespectful, but sometimes you have to fight a thing to the bottom and it’s not comfortable.

Woody Allen even told you on the first day of shooting Blue Jasmine that the take was horrible, and so were you.

But in the end I realized that the location was wrong, the camera was wrong… so we changed everything. And then the scene was cut, it was never in the final footage. You can’t take it personally, you have to listen to it and think that it’s teamwork, that sometimes a director can say something challenging but it doesn’t necessarily have to be about you, but about the product.

How do you feel that the film and fiction industry has changed in recent years with the emergence of platforms and the rise of series? Are you interested in that new channel?

Well, I did Mrs. America (Hulu) with a group of fabulous women. And there are a couple of projects in development that look very good. But in the end, what interests me are really lasting experiences, although only time can tell which ones will be. On the one hand, streaming platforms represent a wonderful opportunity for the audience and also for a lot of people in the industry who have stayed afloat for these two years thanks to them. But this model cannot go forward without being examined.

What is the perceived risk?

It is necessary to analyze the potential monopolies that are emerging from this format, and that are not good for anyone. They are not good creatively and neither for the public. And, of course, they have never been good for the industry. We do not want to replicate the old studio system in a more radical and irrevocable way. I am worried about this. Very worried.

Do you think this system of monopolies is accelerating?

Yes, and I think the public can perceive it. Because everything looks alike. The offer is uniform. There is nothing special anymore. However, going to the movies is still an event.

But after the pandemic, due to fear or routine, cinemas continue to lose viewers, at least that is what is happening in Spain.

Yes, and also in the United States there are a lot of small theaters that have been acquired by the platforms to project their content. But there are still places like a small theater in Pittsburgh called Row House and that has only 50 seats where retrospectives of Tarkovsky, of Wes Anderson are shown… I am confident in that differential value that the cinema can continue to offer and that people appreciate you can still be interested.

The pandemic has changed our consumption patterns, but also other industry tools such as awards and red carpets. Do they still make sense?

I think there are too many prizes. They all look the same and people are tired. But this was already happening before the pandemic. So I think we have to be critical. We have a very good opportunity to change things: to ask ourselves what we want to do, what we want it to look like and, above all, if bigger is always synonymous with better. And I’m not just talking about red carpets, but events in general. We don’t want to go back to that old narrative. I personally don’t want to go back to the good old days because I think they weren’t really that good.

But in the end the old physical events have their magic. Even Giorgio Armani, the first designer to suspend a show due to COVID, has returned to the physical catwalk with guests.

It is a live event. That is why the performing arts are so special. When you walk into a room and you can see the fabrics, hear the music, you are there. You remember. But I think the key is the same in fashion as it is in film. Mr. Armani is always aware of every detail. Even at his age, he is a tireless worker and his control over the quality of the products is incredible. He thinks the more you do, the less special he is. And this happens in all industries, including the film industry.

Source: EL PAÍS

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?)

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?) The Seagull (2025)

The Seagull (2025) Bozo Over Roses (2025)

Bozo Over Roses (2025) Black Bag (2025)

Black Bag (2025)  Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)

Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)  Disclaimer (2024)

Disclaimer (2024)  Rumours (2024)

Rumours (2024)  Borderlands (2024)

Borderlands (2024)  The New Boy (2023)

The New Boy (2023)