Hi, Cate Blanchett fans!

TÁR’s premiere is upon us but before that Cate Blanchett has appeared on three different covers for Vanity Fair, while this is not the first time she has appeared on multiple covers for the same issue, this is the first time where it is multiple covers for three different countries (France, Italy, and Spain) released at the same time. Vanity Fair France, Italy, and Spain September 2022 issue go on sale today, August 31st. Check out the interview and photos below.

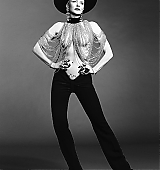

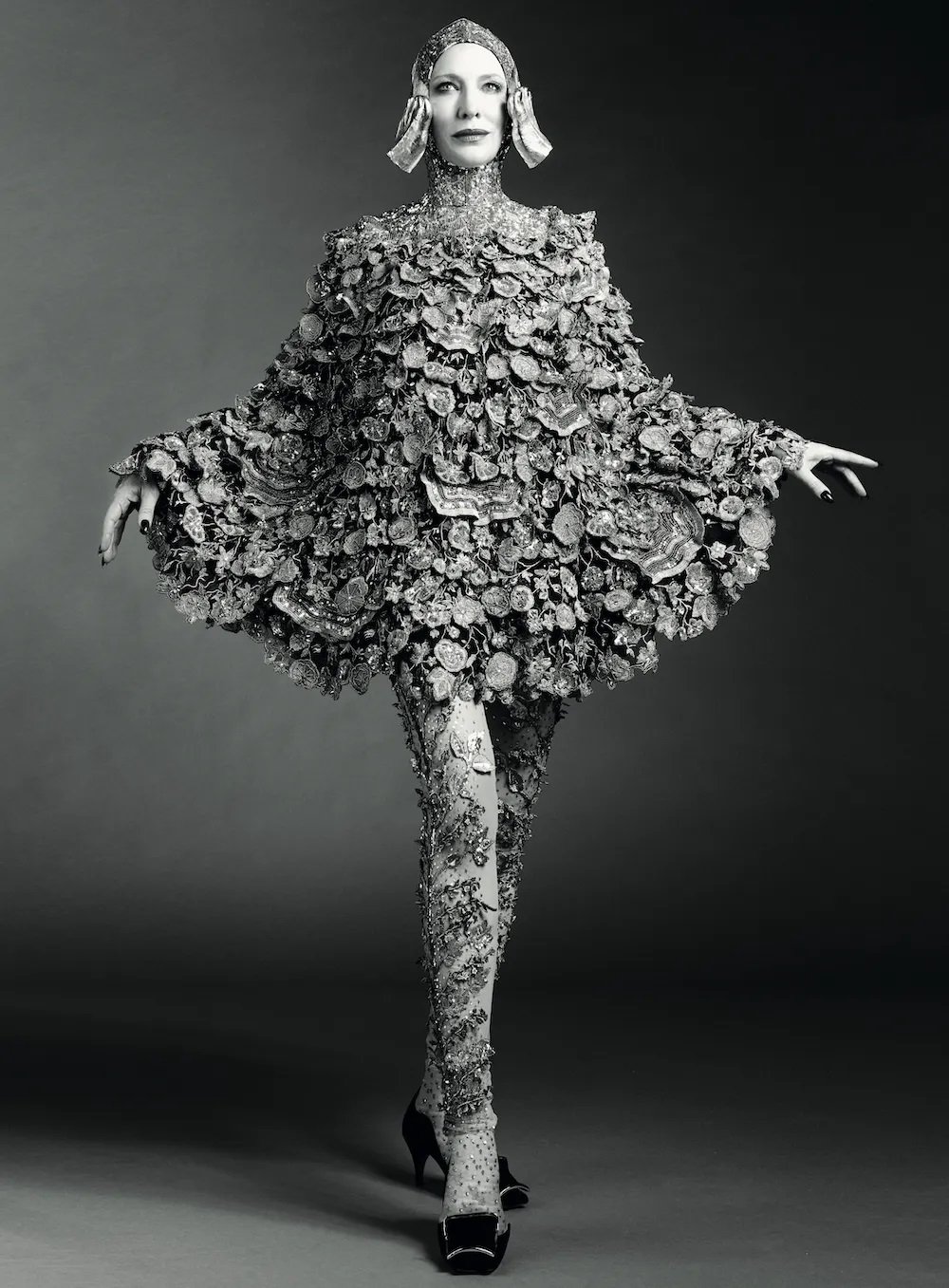

Vanity Fair France — We made this singular choice for the cover of this September Issue, with this portrait of Cate Blanchett photographed by the duo Luigi and Iango. The session took place in London at the beginning of the summer and each edition of Vanity Fair in Europe could choose its image of the Australian star for the front page. We let you imagine the debates within our editorial staff, on the framing, the intensity of the gaze and the chroma. Is black and white the subtraction of life and color? Or the multiplication of contrasts and emotion? We leave you to judge.

Vanity Fair Italy — Three different covers, an international diva and a couple of the most important photographers in the world. To celebrate the Venice Film Festival, Vanity Fair arrives on newsstands with a triple European special edition dedicated to Cate Blanchett, the artist who presents the film Tár in competition at the Venetian festival.

The actress was photographed exclusively by Luigi & Iango, a duo of star photographers with whom the magazine has started a collaboration that will see new and surprising chapters over the next year.

Vanity Fair Spain — The Australian actress returns to the big screen as the protagonist of Tár, the new film by Todd Field. Regarding her presentation at the Venice Film Festival, Antonella Bussi talks via video call with Cate Blanchett about this film in which she gives life to an orchestra conductor and where, among others, topics such as the culture of cancellation and the use of power.

In Tár, Todd Field’s latest film, actress Cate Blanchett plays an orchestra conductor, a role for which she had to become familiar with a job traditionally attributed to men. It is one of the most anticipated projects among those that will be presented these days at the Venice Film Festival, and it deals with issues such as the fear of the passage of time, the abuse of power or the cancellation policy. Many times we have needed female examples that make us believe that evolution is possible, that male hegemony is a questionable totem. “In principle, the conductor should have been a man, in which case perhaps we would talk about it in another way. But the fact that she is a woman takes us into a space from which we can look at the issue more impartially,” the Australian tells us in our cover interview. Art has to be years ahead of society for us to visualize goals and imagine other possible futures. And for that we need the cinema, we need the stars that inspire us, we need Blanchett, sure of herself and sure of working with Field. There is always something exciting about mythical and unprolific authors. Every time they open their mouths we are sure that they will say important things.

If in September 2020, the first year of the pandemic, Cate Blanchett (Ivanhoe, Australia, 1969) presided over the Venice Film Festival jury with her resilient spirit, now, two years later, the actress returns to the Lido to compete in an edition that promises to be full of great stories and illustrious names. In the long afternoon video call that we share, Blanchett tells us about the topics that Tár addresses, the film in which she is the absolute protagonist. I log in ahead of time and am surprised to see that she’s already there. The black screen is named after Cate Upton. It is the surname of her husband, Andrew, the Australian playwright and filmmaker with whom she has been married for 25 years. She wears her hair up, glasses, a beige linen suit, and no makeup. Her voice sounds powerful: “I was looking at email,” she clarifies with her kitchen as a backdrop.

Tár is the long-awaited film by Todd Field, who returns to directing 15 years after his success with Little Children. Lydia Tár, the character played by Blanchett, is a conductor in full professional swing, but also a woman whose shadows are accentuated by the world in which she moves.

— Tár is a brave film. What was it that convinced you to play the lead?

— Look, first of all, it’s already rare for Todd to make a movie. So I wasted no time when he called me on the phone to tell me “I have a script”. And in general, I tend to be slow. I have a thousand things to think about and it takes me two weeks to read a script, but I devoured this one in 24 hours. It was very visceral. I felt that it was about something that affected my body and my spirit. That, coupled with the desire to work with Todd, was decisive in convincing me.

—How does one prepare to play a conductor?

— I asked a friend who is and I realized that it is a bit like being the center of the stage: if you do not have the perception of space, if you do not occupy it, the public does not follow you, does not know where to look or takes you seriously.

I have to be honest: on the one hand I was terrified like never before in my life. There was the pandemic, I had also lived through it, so the musicians had not played important works for a long time and, as if that were not enough, when I raised my arm to mark the rhythm I did it a little out of time. But then I realized that they needed me and I desperately needed them, and somehow the music would flow. I learned the gestures and I am unable to express how wonderful it is to feel how the music flows. It is an engaging experience!

—Indeed, it must be incredible that so many people depend on your gestures.

— All the conductors I have consulted have told me that you have to dominate the podium, you cannot show weakness. It’s a trick, like those of theater actors. You have to pretend that you know what you’re doing even if that’s not the case, it’s a question of leadership. In Australia, I participated in a leadership program and we wonder what it will be like to lead in 20, 30, 50 years. My suspicion is that being a leader will have to include the ability to say “I don’t know” or “I don’t know yet.” Have doubts and admit them. But nowadays the model is different: if you are a leader you have to say “I know, so follow me”. It’s a problem, but that’s the way things are today.

—Lydia, the protagonist, seems to experience in first person all those great issues that today divide public opinion. The first of them, that of age and the passage of time…

— Lydia is turning 50, a special moment in anyone’s life. At that point, you are aware of everything you have already done and wonder how much time you have left and what to do with it. You are at the peak of your life and your career. But what happens when you start to descend from the mountain? We always talk about success, but the path to get there is, without a doubt, much easier than that of relegation, that of failure. That is the theme of the film.

— Another issue raised by the film is the use of power by those who occupy a dominant position. Lydia, for example, uses her charisma to obtain sexual favors, to not always be correct or honest…

— Certainly. And clearly that is unacceptable. The power system can lead anyone to separate from herself. In principle, the conductor should have been a man, in which case we might talk about the subject in another way. But the fact that she is a woman brings us to a space from which we can analyze the matter more impartially. The world of classical music is one of masters, comparisons to composers of the past, and greatness that raises the question of what is allowed in the pursuit of excellence. The question is simple: “What are we allowed once we occupy a position of power? To what extent might the prodigies you meet have been corrupted by it? The film deliberately avoids giving an answer and perhaps doesn’t want to give one either, because questions are always more powerful than any answer. At this historical moment it is interesting to first understand what is happening, without judging. The power of art lies precisely in that: in helping us understand what is in front of us and only then allowing us to judge it.

—Lydia has a partner and an adopted daughter whom she loves and professes great tenderness. In it there is family intimacy but also an opposite desire, that of escaping.

— She is restless because sometimes, when things are going well for you, you feel the need to break them. For artists, creating something often means making something else die. Of course, that’s not what I do, but I get it.

—The film also addresses the issue of cancel culture, of suppression in the name of political correctness. What do you think about that?

— Making movies, music, theater or art is not a political act. What can become so is the way it is spread, digested and processed, but its production itself is not. In my opinion, the reflection that must be done is another: what do we study? I am in favor of studying how things happen in a historical context and asking questions. For example: how did women think at a certain time? Certain ideas today may seem dangerous, but erasing them and not talking about them can exacerbate the danger, because then we would be condemned to repeat the same mistakes. There must be confrontation and at the same time we must confront the systems that perpetuate abuse and prejudice. Only through these actions can progress be built.

—How much of Cate is there in the character of Lydia?

— Lydia’s character made me think a lot about what is allowed and considered acceptable in the pursuit of excellence. I recently spoke with an actress friend about how important Stella Adler, a great acting teacher, was for her career. However, today Stella would be “cancelled” and her methods would be considered excessively brutal. I think that in art a certain brutality is necessary, because if you want to stand out you must have a judge within you, be hard on yourself, have a strong critical sense of what you do. Who cares what others think, it is to their interior that any writer, actor, musician or painter must be accountable, to the point of always demanding more. But this way of generating excellence that we have used for decades no longer works because kindness is now required.

— But then what is the price of excellence?

— I do not know. And I don’t think I’m great. Excellence is my mistress, I court her every day, but she is very elusive!

— More than a lover, perhaps a companion.

— I hope so. However, excellence is different from success. I know many artists who have not received the recognition they deserve. That is the cruelty and riskiness of my profession. And then the obsession with legacy comes into play, as it does with my character. We see this in the Elon Musks of the world, capable of doing anything in order to leave a mark. There is a great human cost, as well as personal and artistic, in that. But what we leave to those who come after is totally out of our control and it is arrogant to think otherwise. You can only decide what you will leave to your children.

—Is it so difficult to know how to manage success?

—Someone told me at the beginning of my career that success reveals who you are, and I think it’s true because it exposes you a lot. But failure is an exceptional teacher.

— How do you survive failure?

— You can always be reborn, right? As long as you’re strong enough. T.S. Eliot said: “In my end is my beginning.” And there is always a new chapter, which sometimes requires a fall to exist. But humility is needed, another undervalued virtue. That’s why for me the film has an optimistic ending, despite everything.

— You’re going to Venice to attend the Venice Film Festival, a big event that we hope will encourage people to return to the cinemas.

— It will be great to go to Venice and, of course, I hope that the festival will help to fill the cinemas. It has been and continues to be a difficult time for everyone. One of little leadership and great economic instability. Women are always the first affected, they lose their rights and control over their bodies. This instability amplifies our desire to get together, listen to music, go out. And to go to the movies, where you find stories that also help to delve into yourself, into the person you are. With the pandemic we have had a great collective experience and we must realize that we are all in this together and we have to be humble.

—You speak of humility, but yours is a truly extraordinary life…

— I’ll tell you one thing: this summer there has been an incredible heat wave in Europe and we Australians are obsessed with water and how to conserve it. Five years ago we wanted to buy several large warehouses for our house in England and people thought we were crazy because it always rains here. But there had already been a drought in Sussex and now we are in this heat. Today I have been watering my raspberries at five in the morning using the water from the tank so as not to waste the main one. If we run out of water, no matter who you are or where you are, we are out of it. We are all connected and we have to be humble.

Sources: VF France, VF Italy, VF Spain, French Interview, Italian Interview, Spanish Interview

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?)

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?) Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)

Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)  Black Bag (2025)

Black Bag (2025)  The Seagull (2025)

The Seagull (2025) Bozo Over Roses (2025)

Bozo Over Roses (2025) Disclaimer (2024)

Disclaimer (2024)  Rumours (2024)

Rumours (2024)  Borderlands (2024)

Borderlands (2024)  The New Boy (2023)

The New Boy (2023)