Hi, everyone!

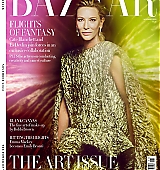

We have compiled the interviews that Cate Blanchett did the past few days as part of promo tour for TÁR. We also found the recorded Q&A from Screen Actors Guild (SAG) screening that happened last Sunday. There are also magazine scans from Harper’s Bazaar UK where Cate is the cover for the November 2022 issue, and Gramophone where she wrote a piece and shared her musical passion. Cate, with Todd Field, also visited the Criterion Closet the other day.

Series 2 of Climate of Change with Cate Blanchett and Danny Kennedy has just been released today. You can click on the link below to listen.

Photos and videos from the NYFF premiere and other appearances will be added on the site in a couple of days so stayed tune for more updates.

Beware of spoilers!

An amazing visit with Cate Blanchett and Todd Field, whose new film TÁR just had its @thenyff premiere before opening theatrically in New York and Los Angeles this weekend! Stay tuned for more from their visit…?? pic.twitter.com/JtZtJWq8GN

— Criterion Collection (@Criterion) October 5, 2022

Cate Blanchett and Todd Field at the Criterion closet

Climate of Change with Cate Blanchett and Danny Kennedy

Climate of Change is back for a second series!

Cate Blanchett & @dannyksfun have teamed up again to bring us positive stories about people tackling climate change.

Listen now: https://t.co/GRe2qTHEi1 pic.twitter.com/cW7wdyGuRZ

— Audible UK ? (@audibleuk) October 6, 2022

Cate Blanchett celebrates our natural world

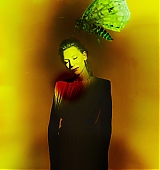

Wearing a shimmering brocade gown and platform heels, a glacially imposing Cate Blanchett carefully picks her way onto the Bazaar cover set, which is taking place in a cavernous studio in north London. Behind her on a screen, a line drawing of a lunar underwing moth, projected to vast size, springs into sudden life. Blanchett shuts her eyes and undulates on the spot, her body seeming to morph into the moth’s, her arms swaying with the slow beat of its wings, their markings embellishing her dazzling dress. For a moment, superstar and artwork become one, captured in the snap of the shutter, as the insect itself might once have been caught and trapped under glass.

“You know, it took me a long time to feel comfortable being captured in a still image, but there was a kinetic quality to what we were doing that I loved,” Blanchett says.

That moment in the studio is the culmination of a project to create a special shoot for Bazaar’s 10th Art Issue, bringing together the actress and the artist Es Devlin, whose magical set designs, fusing sculpture and light, have animated fashion shows, theatrical performances, and concert tours for stars such as Adele and Beyonce?. “I think Es’s understanding of space is extraordinary,” says Blanchett admiringly. “The inside of her mind is so animating – you feel so alive in her presence, and the way she can turn a line of intellectual inquiry into something incredibly beautiful…”

The pair have more in common than a profound understanding of staging and how to make a visual impact. They are both passionate about environmental issues, hence their mutual keenness to collaborate; Devlin will show at COP27 this year, and her latest piece, Come Home Again, commissioned by Cartier and unveiled outside Tate Modern in September, celebrated London’s 243 most endangered species – birds, insects, animals, fish, plants and fungi. Each creature has been carefully drawn by hand, then enlarged, illuminated and mounted within a scaled-down, bisected replica of St Paul’s Cathedral. Every evening for 10 days, a different choir performed a version of evensong inside the artwork, their voices mingling with those of the birds and insects depicted.

“The first step towards these species remaining with us is for us to care about them,” Devlin tells me. “I sometimes spent 18 hours a day drawing them. It’s about paying attention, just observing, and being engaged in quite an intense way with these non-human Londoners.” She has brought a selection of her exquisite line drawings to our shoot, which a team of assistants are pinning up on the walls; there is also a huge model of a human hand, out of which birds and insects are springing (it’s a nod to the scene in Luis Bun?uel and Salvador Dali?’s surreal film Un Chien Andalou in which ants emerge from a human palm, but is celebratory rather than nightmarish, Devlin explains.) “These creatures need to have not only a place in conservation plans, but a place in our imagination.”

This is a sentiment with which Blanchett would doubtless agree. Last year, she starred with Leonardo DiCaprio in Don’t Look Up, the Netflix climate-change satire, and she recently launched her own podcast, A Climate of Change, with her friend Danny Kennedy, an environmental expert. Among the impressive roster of guests who have so far joined her are Prince William, the Prince of Wales, talking about his Earthshot Prize, and Don’t Look Up’s director, Adam McKay. Blanchett also recruited Kennedy to transform the eco-credentials of the Sydney Theatre Company when she and her husband Andrew Upton, the playwright, took over as joint artistic directors in 2008, installing solar panels and rainwater-collection tanks and ensuring that all of the sets were as green as possible.

“Often, the language around climate change is about sacrifice,” she says. “But when you go out to the theatre – or to a movie, or an art gallery – and you have an extraordinary time, and you laugh, and you cry, and you’re entertained, and you eat wonderful food, and then you think: ‘Oh my goodness, my carbon footprint was pretty close to neutral,’ that’s beautiful. If you grapple with these things creatively, you can have beautiful but practical solutions that actually benefit us all. It’s not a sacrifice – it’s an opportunity.”

It’s complicated to find time to speak to her after the photo-shoot, due to her punishing travelling schedule. At 53, Blanchett is more in demand than ever. She has numerous varied projects in the pipeline, from the sublime (Todd Field’s psychodrama Ta?r, in which she turns in a breathtaking performance as a renowned conductor) to the ridiculous (playing an inept Lancashire hairdresser in a mockumentary called Two Hairdressers in Bagglyport, in which she’s unrecognisable beneath a wig and false teeth). There’s also Borderlands, a sci-fi action film; Disclaimer, a thriller television series; and she’s shortly heading back to Australia to play a ‘renegade nun’ in The New Boy.

We finally manage to schedule a Zoom call at 7am, two weeks after the shoot. Blanchett dials in from a hotel suite in Venice, where she’s been attending the Film Festival. The night before, she had been partying at the Ta?r premie?re in black-velvet Schiaparelli trimmed with flowers; now, having overslept, she’s halfway through packing to fly to Telluride, in Colorado.

So, she’s heavy-eyed behind her big tortoiseshell specs, and throughout the conversation, her computer beeps constantly with incoming WhatsApp messages from the school mums, interspersed with alerts that Blanchett has set herself. “This is what my life is like,” she says, laughing at what she calls her ‘early-onset dementia’. “I set alarms all the time. It’s the only way I can remember to do things.” It is a brief but eye-opening glimpse into the intensity of her schedule, and it makes me feel rather sorry for her.

She wouldn’t have it any other way, however. “When I was young, I thought acting was something you did for fun,” she says, recalling how she and her sister would play dressing-up games as children. “Maybe I still think that? It wasn’t about building a career; it was doing these random things.”

“Being an actor has staved off the inevitable decision about what I have to do with my life, because I’ve empathetically stepped into various different experiences, whether they’re fantastical or based in the real world,” she says. “I think I’m probably quite shy, and I find that the best way to get to know people is through making things together. It’s a way of having very active, visceral, engaging conversations with people. It keeps me social.”

Blanchett may possibly be socially timid, but she is professionally courageous – hence the dizzying variety of the projects she’s undertaking. “If I pick up a script, and I can imagine myself [acting] it, I should put it down and let someone else do it,” she says. “Because I think the process of making it and, therefore, ultimately, probably, the experience of watching it will be thin. It’s much more exciting to be outside of your comfort zone.”

There is no doubt that her latest role pushes all her boundaries. Blanchett plays Lydia Ta?r, a gay, internationally renowned conductor of a German orchestra who gets caught up in a #MeToo scandal. The challenging film tackles the thorny issues of cancel culture, social-media manipulation and identity politics, while leaving the viewer free to make their own judgement on the justice (or otherwise) of Ta?r’s eventual fate. The script was written specially for Blanchett by Field, the acclaimed director of In the Bedroom and Little Children, and marks his return to the big screen after 15 years.

“I don’t think I’ve had as visceral a first read of a script since I read Oleanna and threw it across the room,” says Blanchett, who took the lead in the Sydney Theatre Company’s production of David Mamet’s distinctly Marmite play in 1993. “When I read Ta?r, I had a similar response – what is this? I had no idea how to approach it. I said to Todd, ‘This is slightly overwhelming!’ And he said, ‘Well, you can only eat an elephant one spoonful at a time…'”

Ta?r’s downfall is precipitated in part when she clashes publicly with a student who refuses to perform Bach because of the composer’s treatment of his family. I suspect Blanchett would take Ta?r’s side in this particular argument, having herself faced questions about her decision to work with Woody Allen on Blue Jasmine (in which she turned in another scintillating performance).

“People often talk about left and right, up and down, right and wrong, good and bad. I don’t think in those terms,” she says. “Art exists in the grey area. I don’t know the answer to this question, but it’s a conversation that we must have, as artists, as humans, as a society. How do you remain in a robust and brutal relationship with the thing that you are making? You have to have a powerful inner critic, and sometimes that can come out. I have been spoken to in ways that now I could probably go to HR and complain about, but those conversations that were had with me early on in my career made me a better actor. It’s important we speak honestly with one another.”

She always looks for the flaws first, she says, when thinking herself into a character. “There’s an exercise you do at drama school, where you write down everything a character says about themselves; and then you write down what every other character says about them. Somewhere between those often contrapuntal, contradictory things lies some version of the truth. One of the phrases I just cannot say is ‘my truth’,” she goes on, suddenly outraged. “I mean, the truth is the truth, isn’t it? I think language is so important. ‘My perspective’ is one thing, but ‘my truth’? I don’t know what that is!”

Among her greatest challenges was being at ease conducting Mahler’s Fifth Symphony with a full orchestra, to whom she had to speak fluent German. As well as watching footage of Herbert von Karajan, Simon Rattle, Gustavo Dudamel and other great baton-wielders, she spoke to Simone Young, the chief conductor of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. “What women wear on the podium, how they stand – before you lift a finger, it’s a political act, and you have to spend 70 per cent of your energy pushing that aside, simply so you can be a musician,” she says. “The focus you need is twice what a male conductor needs, even now. So my friend said, just plant yourself there. I had to pull on my power pants, put myself on the podium, claim the right to rehearse, and not worry what they thought of me.”

Dauntingly, the Dresden Philharmonic’s programme schedule meant she had to conduct them on her first days of filming. (She had previously agreed with Field that she could ease herself in gently for the first week.) “I said to myself, maybe there’s a gift in that. It meant that I went completely inside Ta?r’s physicality, and what she was born to do, and I did that first, so I knew what was at stake and what she was going to lose.”

Because of the pandemic, the orchestra hadn’t rehearsed major works together for 18 months, instead performing socially distanced chamber pieces. Consequently, when Blanchett gave the downbeat, the musicians came in all over the place. “It was a blessing,” she says, with a chuckle. “We all laughed.” (Messing up early on is a trick she learned while understudying the Australian stage actress Kerry Walker, who told her: “On the first day of rehearsal, I fuck up so badly. Then they’ll think, ‘Oh my God, she doesn’t know what she’s doing,’ and they start to direct me.”) Frankly, however, Blanchett rarely, if ever, missteps; her performance in Ta?r has already landed her the Venice Film Festival’s Best Actress award and she’s now hotly tipped for another Oscar.

When I catch up with her for a final time, she’s back at home in the English countryside and looking considerably more relaxed, her reddish-gold hair swept up in a messy knot, shirt sleeves rolled up to the elbows. Her family and domestic life must be a welcome antidote to the intensity of her career. She and Upton have four children, ranging in age from 20-year-old Dashiell, who’s studying film at university in the US, to Edith, still at primary school. “They enjoy a sense of anonymity here, which I’m grateful for,” she says.

I was once lucky enough to be invited to lunch with her there, and found the house large but not intimidatingly grand, the children forthcoming and friendly, and the atmosphere rather Larkin-esque, with home-made cakes on the kitchen table and pigs and bees in the rambling garden.

During lockdown, the Uptons bought a mini electric jeep to amuse the children; when I ask how Blanchett relaxes, she laughs about driving it around the garden with the dogs in the back. The previous afternoon – “I’m going to sound like Felicity Kendal,” she warns – she had donned a linen apron and wandered up to her greenhouse to decant honey, pick apples and cut sunflowers, and was almost late for the school run as a result. “I completely lost track of time,” she says. “It’s a humbling experience, trying and failing to grow things! But then, when you get seven strawberries, suddenly everyone’s so excited, and you’re like, who wants half a strawberry?” She pushes her hair back from her forehead and grins at me, touchingly enthusiastic. I reflect that it is this ability to wholeheartedly inhabit every role she takes on – whether that’s screen icon, earth mother, complex fictional character or even a moth in a work of art – that makes Blanchett by far the most compelling actress of our age.

TÁR Interviews and Q&A

You can listen to the WNYC Radio interview with Cate and Todd Field:

Now in studio at @wnyc: Cate Blanchett and Todd Field, here to talk about @tarmovie with @alisonstewart. pic.twitter.com/eVb4z2j4FH

— Kate Hinds (@katehinds) October 4, 2022

Acclaimed Australian actor Cate Blanchett says the themes of her new drama ‘TÁR’ galvanized its cast and crew, making the film shoot ‘the most stimulating’ she had ever been on https://t.co/O196s2wm9K pic.twitter.com/6nuoVzGu6T

— Reuters (@Reuters) October 5, 2022

Cate Blanchett Calls Playing an Orchestra Conductor in Tár “the Most Transformative Moment of My Life”

Fresh off of winning the best-actress prize at the Venice Film Festival last month for playing a fictional world-renowned conductor and composer in the psychological drama Tár, Cate Blanchett says her latest movie felt the most “urgent” to make in her storied career. The film, written and directed by Todd Field, explores contemporary themes that have made headlines in recent years, including the #MeToo scandal, the abuse of power, and cancel culture.

“There are a lot of explosive things that come up in this film and societal hot-topic issues that made this cinematic endeavor feel urgent and undeniable to make,” Blanchett said at the film’s New York Film Festival premiere screening Monday night. “Todd Field’s screenplay raises monumental, dangerous questions that the world is dealing with as of this moment. The film can be quite uncomfortable. It can be politicized and disseminated, and some may even feel disgusted by the characters, but at its core this is a nuanced, intimate, human story of a woman that synthesizes many things. It can be said it’s an examination of power, but for me, I want audiences to make their own interpretations and inspire lively debate.”

Blanchett stars as Lydia Tár, the first woman conductor at the helm of the Berlin Philharmonic, the major German orchestra that is considered to be the world’s greatest. Her great talent on the orchestra podium and her keen musical scoring have earned her EGOT status, among other accolades, and made her a master class guest lecturer at Juilliard, with a memoir on the way. She is at the pinnacle of her career and wields great cultural power. She begins to crack when the family of a female former student accuses her of sexual misconduct, threatening to derail her career and success.

Like Lydia Tár, Blanchett, a two-time Oscar winner, is at the height of a long and distinguished career. As with Blue Jasmine, Elizabeth, The Aviator, and more, she’s once again earning rave reviews and strong awards buzz for her performance in Tár, which hits theaters on October 7. When asked how she handles fame, Blanchett admitted that “it’s not easy” being in the spotlight.

“It’s taken me a long time to deal with fame. I come from the theater. I never expected to have a film career,” said Blanchett. “It’s uncomfortable to be looked at. It really is. But it’s such a privilege and a pleasure to have had all the opportunities I’ve had in my career.”

To portray a highly lauded orchestra conductor, Blanchett studied the technique of holding and moving the baton, which is called stick technique, by collaborating with the Dresdner Philharmonie, a German symphony orchestra based in Dresden. She acted as the lead conductor by rehearsing Mahler’s Symphony No. 5, the same piece her character grapples with in the film, alongside the orchestra. The Australian star admitted the experience was a daunting task.

“To beat with one hand and shape the sound with the other hand was difficult. It’s such a mix of different skills and emotions,” said Blanchett. “But I must say it was the most transformative moment of my life. There’s this intense feeling of an electric charge, giving the downbeat and hearing this big sound coming back at you. It’s something that I’ve never experienced before. In that space, standing at the podium, you really do feel like you’re the king or queen of the world.”

Cate Blanchett Says ‘TAR’ Is “About The Corruptive Nature Of Power”

“I think the film is also about many things, but it is a medication on the corruptive nature of power,” Blanchett says. “I think, in the same way that the mobile phone influenced the way narrative unfolded, we haven’t even processed the ramifications of the #MeToo movement, Black Lives Matter, and the pandemic. We are altered by these things, positively and negatively. Already, the #MeToo movement is talked about in pejorative, negative terms, as much as had a profoundly positive effect in awakening people’s consciences. But we’re changed by it. And so, any film that is alive now will have reverberations with those things that have happened to us as a species. This film is no different. But it’s not about that. You know what I mean? But of course, it’s a texture and influences the atmosphere in the film.”

Over the course of our conversation, Blanchett discusses her inspiration for Lydia, how she learned to conduct a major orchestra, whether her mother is a fan of her character in this particular film, and, much, much more.

The Playlist: Thank you so much for taking the time. I know it’s been a long day for you of doing press, so I do appreciate this.

Cate Blanchett: No, no, no. I can’t tell you. It’s been such a pleasure to sort of begin to talk about the film. Any film that I’ve ever been involved in to somehow define. It’s so elusive and about so many things, so yeah. It’s been actually really helpful to try to understand the beast.

TP: The film tells us so much about Lydia, but in many others ways, it doesn’t tell us a lot about her, at least parts of her life. I don’t want to spoil anything for people who are reading those before they saw the film, but we obviously learn things about her that we might not have initially suspected.

CB: Yes.

TP: Were there things that Todd told you about her backstory specifically or did he sort of just give you the script and let you fill in the blanks yourself?

CB: Well, like when you read any great screenplay, it asks so many questions, and so much of the information is there, not necessarily readily accessible on the first read. But as you begin to mine the script, a lot of that material is there. And so, Todd didn’t tell me much. Initially, our conversations were intensely practical, because before I could get to even first base with playing the role, there was so much groundwork that I had to do in order to be able to play the scenes, in order to even approach who she was, just technical stuff, in terms of languages, and I don’t just mean German. The musical language and reigniting my ability to read a score and revisiting piano, and then, of course, the art of conducting, which I had to put my toe in that very deep and complicated water. So, it was very practical at first.

And then once we got closer to time, I started asking a lot of questions. This is where he’s such a great director is he was more interested in me finding my own way to it. He didn’t want to give me a ready easy answer. And in my time with any great acting teacher that I’ve worked with or any great sort of public intellectual or academic, they always ask you a question which provokes another question within you. So he would throw ideas into the mix as we were shooting, things that didn’t necessarily end up in the final edit of the film, but made the back story for Lydia so alive. And I think, I hope, for an audience, that’s what makes her such a rich character. So he was really judicious about what he said. He was sort of waiting for me to unearth those jewels if you know what I mean.

TP: Absolutely.

It was one of the most intense and kind of landscape-changing, groundbreaking, whatever the description is, collaborations that I’ve ever had. It was so dynamic and alive.

TP: I caught a recent interview you conducted where you thought that the idea of learning how an actor learns how to conduct or whatever is sort of boring, and you were wondering why people would be so curious.

CB: No, no, no. I didn’t mean that at all.

TP: Oh.

CB: I don’t want the audience to see my homework. You know what I mean? You want them to be transported and to believe absolutely that this person is one of the world’s greatest conductors. So I had to do that homework, but I don’t want the audience to be taken out of the movie thinking about that stuff. Do you know what I mean? That’s what I mean. I don’t want to break the spell of anything that Todd has created by over-describing the process.

TP: Which I totally respect and understand. It actually goes to my question. You have these scenes where you are conducting symphonies and rehearsals and it starts and it stops as any rehearsal would. And I know that you worked with conductor Natalie Murray Beale, but what was the mechanism to make that work on set? Clearly, you did not want even a casual classical music fan would go, “Oh, that would never happen like that.”

CB: Exactly. It’s not a film about conducting. You have to know that conducting is as natural and essential to Lydia Tar as breathing is. I was fortunate. I was working in Budapest and I was taught piano by an incredible concert pianist, and I learned a lot about the process of conducting from her. And Ilya Musin, who’s one of the great conducting teachers, it’s amazing what you can find in YouTube, particularly during a pandemic when you couldn’t meet face to face. I watched his master classes over and over and over again to understand the concept of what the right hand did and the left hand did. The woman who was teaching me German teaches German to opera singers, Francisco Roth, and so she was really across the musical language and the relationship of the conductor to the orchestra. And so, I had all these amazing people, various different points of insight, and also then, for me, having gone to a lot of classes of music concert myself and having heard the music, I then watched every single conductor I could get my hands on from different generations, from different cultures in different sized orchestras, their different way in to see. I realized very quickly that their form of communication was entirely idiosyncratic, and then there are textures in the film which aren’t, as I said, in there.

I imagine that she was the child of deaf parents, so how does sign language influence the way she conducted and her relationship to sound? She has an acute sensitivity to sound. But it wasn’t until I did all that homework, it wasn’t until I stood up in front of the Dresdner Philharmonie who were profoundly generous with … Even with the entire cast and crew. When you raise your hand, you get the downbeat, and the sound starts, and you find your own way with them. So, they had to act. It was outside their comfort zone, and I had to conduct them, which was also outside of my comfort zone. And so, somewhere, like any conductor in any orchestra, somewhere between us, the music happened. And of course, there was a lot of groundwork that needed to be done in terms of selecting [the music]. Todd had written these rehearsal scenes, but then Natalie and I went through them all and said, “Well, what about this piece? This piece with 19 bars would be great and there’s a dynamic counterpart to the previous six bars that we’ve done in rehearsal.” So then, we suggested those pieces to Todd and he edited them, and then I just listened to them on repeat, on repeat, on repeat. And of course, listened to all symphonies to see how this one differed or echoed, and read a lot about Mahler, because trying to delve into the process that great conductors do, which is to give a context and a take on the music.

TP: Thematically the film is tackling a number of subjects, but it really touches on the recent trends of the #MeToo movement and cancel culture. Did your own opinions on those topics influence your portrayal of Lydia, or is it more Todd’s voice in that regard?

CB: It’s many things. There’s a line in the script where it says right at the beginning that, “Lydia Tar is many things,” and that she’s had a varied career. I think the film is about also many things, but it is a meditation on the corruptive nature of power. I think, in the same way, that the mobile phone influenced the way narrative unfolded, we haven’t even processed the ramifications of the #MeToo movement, Black Lives Matter, and the pandemic. We are altered by these things, positively and negatively. Already, the #MeToo movement is talked about in pejorative, negative terms, as much as had a profoundly positive effect in awakening people’s consciences. But we’re changed by it. And so, any film that is alive now will have reverberations with those things that have happened to us as a species. This film is no different. But it’s not about that. You know what I mean? But of course, it’s a texture and influences the atmosphere in the film.

TP: Many actors will say that no matter what your character does or has done, you have to believe in them or at least try to understand what they’re thinking so that you can play them. Did you inherently think that Lydia was a good person, or do you feel like everything she has done has been for her own benefit?

CB: I don’t think about things in terms of good and bad. My mother had said to her friend, because my mom has seen the film, she warned her friend, “You won’t like her.” But I think it’s more accurate to say that you may not want to like her because Lydia does things that we could all possibly do ourselves when no one is watching, and she’s very charismatic. The personalities of conductors often cement their reputations. She’s also enigmatic. She’s also human. And so, it wasn’t about me thinking she was good or bad, but I did understand her. The “liking” her or thinking she was good never came into it for me because I find that quite a general way to look at someone or a situation. I like this. I hate that. I understand the sacrifices and the compromises that she had to make to get where she got, and also I understood how brutal and how disciplined she had had to be with herself, and also often with other people because when she felt that they were holding back because of fear.

I think that the tragic thing is that once she’s got into a position of power, once anyone gets close to power, just how seductive it is and how difficult it is not to be changed by it, and how desperately one can want to hold on to it. Peter Brooks says this fantastic thing, that, “You’ve got to hold on tightly and let go lightly.” But that’s really difficult. Look at all of our politicians. Once they’re in power, they spend most of their time trying to hold on to it as a flame, and we’re moths, and it takes an inordinate inner strength and an incredible spirit to let go of power. So, I think I was trying to understand that situation.

TP: Does it bother you if people ask you if you based Lydia on anyone you know?

CB: No. No. No one person in particular. I looked at the tortured nature of Carlos Kleiber. One of my favorite conductors is Bernard Haitink. I’m absolutely inspired every single day by Nathalie Stutzmann, who’s been a contralto who’s now moved over into conducting through being a singer, and she’s about to take over in Atlanta, which is really exciting. There’s an incredible, very rough, raw documentary about Antonia Brico. I thought about [Herbert] von Karajan and [Claudio] Abbado, all of these people, [Valery] Gergiev, how politically compromised he has become to get how massive his career is and his conducting style.

So, it was sort of all of those, all many of those people, and then also I thought about the CEOs of major banking corporations and massive architects who don’t necessarily make the work anymore, but are across the construction of buildings, and how, in my own experience, I think running a major cultural institution, how you can get isolated from the artists that you’re working with because you have a corporate responsibility as much as you have a creative artistic responsibility. So there were a lot of things that were coming into play with me, but it wasn’t based on any one person in particular.

TP: When you saw the final film, what did you come away with the most? What was your reaction to how it all came together?

CB: I didn’t see dailies at all. It was fast and furious. I was so kind of inside the experience with Todd and with Nina and everybody. I saw it with my husband, thank goodness. I fell into the film, which I think is a testament to Todd’s filmmaking. I just thought there were some things that we shot that are no longer in there, but they’re sort of homeopathically in there. If that makes sense.

TP: It does.

CB: And the first time I read the script, I found the end quite tragic, but I was so uplifted by the end. I thought, “I really want people to see this,” and I wanted them to see it in the cinema. I was bowled over by the sound as well, and the silence. One of my favorite parts of the “Mahler’s Five,” for instance, is the silence at the end of the scherzo before the adagietto begins. I feel Todd’s use of silence was really powerful when in a film about music. So, there were so many parts of it that I felt like I wanted to go back and watch it again. He’s such an extraordinary filmmaker. I feel so, so deeply lucky to have worked with him.

Full article on The Playlist

Cate Blanchett on Learning How to Play Piano and Conduct for ‘Tár,’ How Movie Depicts the ‘Corrupting Nature of Power’

On the red carpet at the North American premiere of “Tár,” Blanchett spoke with Variety about the parallels between Lydia Tár’s ferocious musical ambitions and her own illustrious acting career.

“Any parallels between my experience and her experience will just be there,” Blanchett said. “I had the experience of running a major cultural institution. Lydia is an artist, too. She’s a musician running, as the film describes, one of the greatest orchestras in the world. With that comes a lot of corporate responsibility, which can have an impact on your relationship to what it is that you do as an artist.”

Blanchett, a two-time Oscar winner for her roles in 2005’s “The Aviator” and 2014’s “Blue Jasmine,” said that she “understood that dynamic” despite not being a musician herself.

“All of the musical terms, the relationship to the score, the ability to conduct and play on the piano — all that stuff I had to learn,” Blanchett said. “Her experience is quite different, but you don’t have to be an artist to understand the corrupting nature of power.”

During a Q&A discussion that followed the “Tár” screening in Alice Tully Hall, Fields revealed that he wrote the entire script with Blanchett in mind — long before she agreed to sign on for the film. The second person to join the project was composer Hildur Guonadóttir, who previously won an Academy Award for her work on “Joker.”

Cate Blanchett and Todd Field on Method Acting, #MeToo, and the Movie Theater Crisis

“TÁR” has a lot going on. Director Todd Field’s first feature since 2006’s “Little Children” is an immersive acting showcase for Cate Blanchett, who plays the revered Lydia Tár as if her life depended on it. As the composer overseeing a symphony in Berlin when a scandal derails her career, Blanchett inhabits the character in every scene with stunning precision. Unlike Field’s previous work, the movie is a slow-burn immersion into Lydia’s world that often verges on documentary when it isn’t an unsettling psychological thriller or a pitch-black comedy of errors.

Beyond all that, “TÁR” is a treatise on modern times. Lydia’s experiences with social media and repercussions for her actions register as an angry response to the age of accountability. Yet even as the movie premiered to raves Venice and Telluride, Field and Blanchett have been careful about how much they have addressed these issues in limited press for the movie.

The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

IndieWire: This movie is saying a lot about the world we live in today. It must be hard to discuss in interviews.

Cate Blanchett: There’s so much to talk about.

Todd Field: There’s a lot to talk about.

CB: Yet it’s one of the hardest movies I’ve ever had to talk about, because it’s so hard to define. It’s about so much.

So much about “TÁR” is built around Cate’s performance. Todd, how much did your initial script change as a result of her involvement?

TF: I sent Cate the script and I’d written the script for her. I didn’t really have to any language to give her. It just started a very immediate, rich conversation between the two of us in September 2020 and we’re still having it.

CB: The character came out of those rich conversations. When I read it, I was so daunted by the ask of it — not just what was necessary to play the character, but also the depth of questioning in the screenplay and my relationship to it, which kept shifting depending on which scene we were shooting or which relationship we were focused on that day.

When the cast started to come together, Nina Hoss elevated it yet again. Then Hildur Guðnadóttir got involved to do the music, and I thought it doesn’t get much better than this. My job was not just to rise to the occasion of the screenplay but the quality of the people I was working alongside.

Did you bring Lydia Tár home with you?

CB: Well, the pandemic was still on and my kids were not as free to come and go. It was really very lonely in a strange way, and running a major cultural institution is a very lonely experience. That was life imitating art. There was much to do in terms of the conversations that Todd and I were having. As we got on, we would occasionally have the odd dinner. In a film that is asking big metaphysical and existential questions, it was a very practical experience. The night before he’d be prepping and talking about what needed to be done the next day. Yet when we were working with the Dresden orchestra, I woke up with my hand in the air, moving sound.

TF: We even tried to bring that into the film. There was a certain point where we had her do that.

CB: Work dreams. We’ve all had those.

Where do you fall on Method acting? Did you try to stay in character between scenes?

CB: There were some parts of the character’s situations or intensity of the focus that I didn’t quite drop in between setups. I don’t know if it’s from spending years and years onstage, but I have the ability to be objective and subjective simultaneously. You have to know where the camera is: OK, I’ve got to rotate more than three quarters because otherwise you’re not going to see into my eye and that’s really important.

At the same time, you have to allow this thing to flow through you. Todd always has the camera in the right position. So when he was setting up, I saw the position of the camera as a proscenium: If I stand stage-right, it’s going to mean something profoundly different than if I’m center-stage left. You were very generous about letting us know what the frame was so we know how best to use it.

I don’t know if you find this, Todd, but for me, it’s not so much that you take the character home each night. It’s more about you focus on when you’re walking on the street at night during the odd day off we had. I would hear things differently. I’d come into a room and notice the curtain as opposed to the bathroom. Your focus shifts.

TF: The whole world starts talking at you based on the thing you’re working on.

CB: Which is a privilege, because you are seeing the world from a different point of view.

And that point of view deals with a very sensitive subject in this movie — essentially cancel culture. The character is put on public trial due to reports about her behavior. How much did you see this story as a microcosm of larger issues?

TF: The classical music world is a rich and interesting one for me, but in terms of the story, it’s a backdrop. It could’ve been any kind of pyramid scheme, any kind of power structure. It could’ve been a multinational corporation or an architectural firm. Pick your poison. In all our conversations, we talked about this examination of power — how we look at power and how we decide the way we look at it.

CB: And who benefits from it.

TF: If you really want to talk about power and the long reach of history — the abuse and complicity of power, how it corrupts, all these clichés we’ve grown up with — you have to reckon with the idea that there is no black or white. To find the truth of something requires a little more rigor.

There’s a scene where Lydia is a guest lecturer at Juilliard, where she takes a young student to task for resisting Beethoven and Mozart because they were white men with questionable personal lives. Was this based on something real?

TF: I have friends that teach and that’s one of the inspirations behind the scene. There’s another bigger idea behind it, which is what you would tell your younger self. The student is representative of who Lydia Tár was coming out of Harvard at 24, wanting to push the boundaries, wanting to do experimental music, wanting to bust up the establishment, but she’s gotten past that. She’s at another point in her life. It’s like she’s saying, “Yes, there’s this, but it’s not mutually exclusive.”

It doesn’t go very well for her.

TF: In terms of talking about power in a more thorough way, what’s potentially troubling is when conversation is extinguished and we don’t have the ability to walk in one another’s shoes. I don’t need to be a cobbler to understand whether my shoes fit or not. We all have the ability to try to see someone else’s point. My older son wanted to go study rhetoric at Berkeley. It’s one of the oldest schools in America where you can do that. The idea of debate as a healthy part of social discourse is so fundamental to Western civilization and the idea that it would be extinguished or somehow neutered is frightening.

Cate, when did you start to be more cautious about how you discussed ideas in public?

CB: I’ve always been cautious about interfacing with the media. I’ve always been very private. There are not a lot places where you can have nuanced debate about complicated issues. We haven’t even processed what’s called “The Black Lives Matter #MeToo Moment.” What do you mean? It’s not over. We’re still living through this.

A huge part of that process is rage. If it’s channeled correctly — if heard and understood and listened to — rage is a really, really important transitional tool and is totally understandable. I feel like we’re in a moment of profound transition, which is terrifying for some people. But we’re used to the churn of change because we’re making things.

How do you feel about the way people, as well as storytelling, can be judged through a moral framework?

CB: I think there are certain behaviors that are intolerable. But when it comes to things like banning books, you have to understand the context under which these books were written, even if they may not be your taste. You may find them offensive, but let’s talk about why. I’m much more interested in igniting the conversation with people who think differently than shutting the conversation down.

TF: It’s the times we live in. This is not a social treatise on this moment we’re having. It’s an interesting conversation to have. That scene in the classroom is just the reality of what we live in. The important part of this scene for that character is having a conversation with herself that she’s not successful at having.

CB: She’s been trying to sweep it under the rug. We’ve been talking about origin stories a lot – the connections that conductors have to their mentors is incredibly important in cementing their unassailable right to play their music. But a lot of Lydia’s origin story is invented. So what does that mean? Does she not have a true connection to her origin story or does this one allow her access to a space that unleashes her talent?

When you first started getting attention for your roles…

CB: Did I make shit up? [laughs]

Or feel like you were being judged in ways that were beyond your control.

CB: It sounds a bit like a copout to say that it was a different landscape, but it was that. I came to making films very late. In dog years, my career was almost over as an actress. My first role was when I was 25. I didn’t expect it to continue. I thought I had five years. I thought at 35 that they put you out to pasture as an actress. That’s certainly changed. That’s because women are at the helm more. They’re not the exception anymore. There are a lot of female-driven narratives. I hate that term. I think there are a lot of good women making good shit that’s being seen. They’ve always made it.

TF: If you look at the birth of Hollywood, the great filmmakers that are long-forgotten are female, as were the great screenwriters and editors. There was a shift in Hollywood after the pre-Code days where it became much more patriarchal. But the origins of Hollywood and narrative filmmaking really began with women.

CB: But it was also international. I think one of the world’s greatest filmmakers was Larisa Shepitko. She only made a handful of films, but my god, I can’t unsee the movies that she’s made.

Since you bring it up, does this mean you plan to work with more women directors?

CB: It’s so random what we end up doing. A lot of it has to do with family and time and who approaches you and when you’re available. It was immaterial to me what gender Todd was. It was just the conversation.

Todd, it’s been 16 years since you made your last movie. How much has the industry changed since then?

CB: You used to do interviews on phonograph, didn’t you?

TF: Direct to disc. [laughs] I mean, nothing has changed about making a movie. I think the world for cinema-goers has changed drastically in a way that I probably needn’t add to. Other people have said it at least as well or better than I could and have been attacked or inflamed for it. But let’s put it this way. I went out to tech theaters in New York today and it was really depressing. Super depressing.

Because of the projection quality?

TF: No. At the beginning of the pandemic a lot of us put in what we could to try to support independent repertory houses, the arthouses in America. We knew that since their margins were so close anyway that there was a good chance they’d close up and die. Should that happen, we’re all in real trouble.

We’re very lucky we have a place like the New York Film Festival 60 years and going or a place like the San Francisco Film Festival that’s the oldest film festival in America, but most people can’t get to those things. What about having a single-screen house you can go to? They’re disappearing. So now you’re showing a film somewhere with paper-thin walls where you’ve got a different kind of movie bleeding over into your house, with seats that you can’t really sit in, screens that aren’t maintained, and an infrastructure that has no love at all. You’re a long way from New Yorker Films or something like that.

CB: But go and see this movie in the cinema! [laughs]

TF: I may be sitting here shilling for this movie, but this is something that absolutely has to be addressed: the fact that there is not a standard. It’s one thing to rail on about the death of film and how we have to keep the photochemical process alive, but that’s just a line item that’s not going to happen anymore. I can tell you that from shooting advertising.

Because it’s too expensive?

TF: It’s not. We used to make $100,000 Roger Corman movies and the line item budget that was expected was that we were shooting on film, we’re doing dual mag, we were in the bar afterwards with the crew, we’re watching that together as a group, we’re getting off on that and shooting the next day. It was an accepted part of doing business. It’s just that it’s not accepted anymore. That’s why film died. It wasn’t supported. By the same token, we have a dying arthouse community.

CB: It’s unsupported.

TF: It’s a broken infrastructure to actually go and see cinema. I’m not just talking about end-of-year cinema. I’m talking about world cinema. I’m talking about being able to see things with a collective community and walking out and feeling different. I remember reading this book about Kie?lowski where he said he resented that people always said theater is a different kind of collective experience but not film. He said that’s bullshit. You come in and you feel that energy in the room. The only difference is the performers. If you want people to go to the cinema, to have an immersive experience and sit together with other people, you had better give them the opportunity to do that properly.

Cate, you often serve as a producer on your projects through your Dirty Films banner. I was sorry to hear that you won’t be making an adaptation of “A Manual for Cleaning Women” with Pedro Almodóvar.

CB: Well, look, it’ll happen in some other form. I adore Pedro and totally respect him. He’s got to work in the language he feels like he can thrive best in. Maybe we’ll make something better. It just won’t be that.

How does your awareness of the fragile ecosystem for getting films made and released impact the work you do as a producer?

CB: My husband and I produced many, many shows a year when we were running the Sydney Theatre Company. Working on films is just an extension of that. It’s just a different medium. But you have to be really careful. Some films can still live and breathe on equal measure on a small screen and some can’t. You have to be really careful who you partner with from the get-go. That’s the idea of the creative producer: someone who has grown up on-set, who understands how a script is developed, and how a movie is made. But they also have a financial sense and ability to understand where to place that movie and distribute it. That role is a dying art, and it’s why a lot of actors and directors are stepping into it.

They’re invested in the success on a creative level.

CB: They know they have to care for the thing from soup to nuts. A lot of times, things are just thrust out, and it’s immaterial to the producer what screen it’s placed on or what the rollout is. When you’ve been in the industry for a while, you’ve seen the ups and downs, not necessarily because of the quality but simply how projects have been handled. I’m quite passionate about being involved in that. I do care about what I make. Sometimes it doesn’t work. No one tries to make a bad movie, but if it’s good, you want to know that it has a fighting chance of finding an audience.

Post SAG Screening Q&A

Cate with Todd Field, Nina Hoss, and Sophie Kauer attended the Screen Actors Guild screening Q&A last Sunday. It was moderated by Adam Gopnik.

Magazine Scans

Gramophone Magazine Awards 2022

Harper’s Bazaar UK November 2022

Source: Harper’s Bazaar UK, WNYC, Vanity Fair, Variety, Indiewire

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?)

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?) Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)

Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)  Black Bag (2025)

Black Bag (2025)  The Seagull (2025)

The Seagull (2025) Bozo Over Roses (2025)

Bozo Over Roses (2025) Disclaimer (2024)

Disclaimer (2024)  Rumours (2024)

Rumours (2024)  Borderlands (2024)

Borderlands (2024)  The New Boy (2023)

The New Boy (2023)