Hi, Cate Blanchett fans!

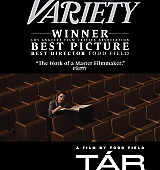

We have gathered the interviews that have been released this past week as TÁR continues to expand outside the US. The gallery has also been updated with some stills, FYC posters, and events that Cate attended this month.

Apart from Critics Choice Best Actress win last week, Iowa Film Critics Association, North Dakota Film Society, and Seattle Film Critics Society also named Cate ‘Best Actress’. She received nominations from Midnight Critics Circle, Chicago Indie Critics Awards, Houston Film Critics Society, DORIAN Film Awards, GoldDerby Awards, Online Film Critics Society, Kansas City Film Critics Circle, and Vancouver Film Critics Circle.

Congratulations, @tarmovie! #AFIAWARDS pic.twitter.com/kWxo1eFD94

— AFI (@AmericanFilm) January 13, 2023

Extremely funny acceptance speech from Cate Blanchett pic.twitter.com/XGgJJoS99D

— Ryan Swen/???/Sun Tianxing (@swen_ryan) January 15, 2023

Things got off to a convivial start at the 48th Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards with a reel of clips highlighting each of LAFCA’s 2022 honorees, which were announced last December. People chuckled at a scene of best actress winner Cate Blanchett melting down in Tár, aww-ed at a clip from best film not in the English language winner EO and clapped along to the “Naatu Naatu” musical number from RRR, the winner of best music/score.

One of the two winners of the newly-degendered best lead performance award, Bill Nighy of Living, said of the other, “To be associated in any way with Cate Blanchett? You have my attention.” Blanchett, for her part, praised a host of fellow actresses, including the star of the project with which her film tied for best film, Everything Everywhere All at Once, who is also widely thought to be her primary competition for the best actress Oscar: “Michelle Yeoh blew my socks off and my underpants and everything else.”

The Everything Everywhere and Tár teams’ mutual affection was further emphasized by Everything Everywhere’s producer Jonathan Wang, who told the Tár team, “Thank you for being the apple to our orange,” and by Tár’s Todd Field, winner of best film, best director and best screenplay.

Field additionally noted that he was last at the LAFCA Awards 21 years ago, when he was feted for his first film, In the Bedroom. After his second film, 2006’s Little Children, it was 16 years before his third, Tár. “I’ve kept the lights on pretty much just directing commercials,” he acknowledged. “I truly love making films, but it had been an awful long time for me, and I was really scared. I didnt know if I knew what the fuck I was doing.” Blanchett, in her speech, and LAFCA, with its trio of accolades, reassured him that he did.

Cate Blanchett on playing her most complex character yet in Tár

There aren’t many actors who could open a film with a scene depicting a full interview with a New Yorker journalist and have it be an utterly engrossing introduction to a character, but the inimitable Cate Blanchett does just that.

Playing the titular role in Todd Field’s Tár, a character study exploring the reputational downfall of the fictional first female chief conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic orchestra, Blanchett is omnipresent throughout the film, in almost every shot, never mind every scene.

“I’ve never encountered a character as elusive and as complex as Lydia Tár,” says the 53-year-old star, describing how she embodied the character. “I’m very language focused, and, of course, the first quarter of the film is very top-heavy with language, but then that sort of peters out into silence. In a way, I started with what she loved. I started with the music, I started with this thing that had kept her alive and kept her sane, and that she was risking losing because of the events that unfold in the film.”

In keeping Tár such a ubiquitous figure in the film by making Blanchett’s performance the focal point of the entire narrative, Field makes it abundantly clear just how influential and powerful the character is.

We see her behind the podium, commanding her players; in meetings where she is deftly holding her own among her white, male musical contemporaries; at home with her adopted daughter Petra, where she stands up to playground bullies with biting words that are enough to threaten an adult into servitude; and crucially with her young, attractive female players and assistants who clearly hold more than a professional admiration for the conductor.

“There were very simple rules for the film,” says writer and director Todd Field when asked why he wanted to make Tár such an intense character study.

“Trying to understand why is this happening — this character got into whatever she did, like all of us, because she had a great love for something, she had a love for music, it was going to transform her and change her. And it did. And now she’s sitting atop this power structure, and she’s bifurcated.”

Despite conducting being a “hierarchical, white male-dominated canon”, as Blanchett describes it, the fictional Tár has ascended the industry’s ranks.

“It is a fairy tale, in a way,” says Blanchett. “Even though there are some extraordinary female conductors, there always have been, they just haven’t been provided the opportunity.

“As a woman stepping up onto the podium, 70% of their energy is having to push the politics of that step up outside, so they’re considered to be the extraordinary musicians that they are. But the film’s not about that,” adds the star.

“The fact that they’re in a same sex relationship, the fact that they’re women in a very hierarchical, white male dominated canon. It’s a texture to the film, but it’s not the narrative.” Instead, Field is more interested in the dynamics of power — how it corrupts and how it is facilitated by others.

Full interview on The Irish Examiner

Cate Blanchett in conversation with Classic FM

“I didn’t base the character of Lydia Tár on anyone,” Cate Blanchett told Classic FM breakfast presenter Tim Lihoreau in an exclusive interview this week.

“I thought about [American writer, philosopher, and political activist] Susan Sontag as a public intellectual, as much as I thought about Alma Mahler, as much as I did about any contemporary conductor.”

Blanchett plays the powerful fictional maestro of the Berlin Philharmonic in the film, Tár, which was released in cinemas in the UK last Friday. As the first major film about a woman conductor, her portrayal has drawn interest and critique from the classical music world, though Blanchett points out, the film as a whole, is a very nuanced adult examination of the world in which we live.

“It’s not a film about conducting,” Blanchett told Lihoreau. “It’s not a film even really about classical music. The character could just have easily been a master architect or a head of a major banking corporation.

“I think it’s a very provocative film, but it really is an examination on the corrupting nature of institutional power. That affects everybody, no matter what your sexual orientation or your gender.”

While Blanchett spent her childhood in piano lessons, and at one time sang in a choir, she had never conducted before.

Learning to conduct is no mean feat on its own, but Blanchett also had to learn to conduct Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, a work which takes a central role in the film.

“Todd Field, the director,” Blanchett explained, “he’s very big on authenticity, as are the orchestral musicians we worked with from the Dresden Philharmonic [who posed as the Berlin Philharmonic]. If you stand up there and you’re inauthentic as a conductor, they’re like ‘get off the podium!’, so I had the privilege of actually conducting the orchestra for the time of the film.”

Prior to the production, Blanchett was working in Budapest, a place where Mahler wrote a lot of his music. Blanchett formed a relationship with concert pianist, Emese Virág, a teacher at the Budapest Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music.

“She talked to me a lot about the history of this music, which was incredibly valuable. And it was a very, very important relationship, I struck up with her.”

During the interview, Blanchett recalled her childhood years learning to play the piano, when her teacher told her, “I don’t think you’re a pianist. I think you’re an actor”.

She continued, “So, I could read music… but nothing could have prepared me for standing on the podium and giving the downbeat and having that sound come back at me [from the Dresden Philharmonic]”.

As well as learning the music, Blanchett also tried to learn and replicate the mannerisms of some of the world’s greatest conductors.

“I’d heard that Simon Rattle, had talked about hearing music all the time,” Blanchett continued, “and he realised quite quickly that that wasn’t, ‘normal’ – not everybody heard that music in their head all the time.

Another musical characteristic embedded in the storyline is Tár’s misophonia, which in Blanchett’s words, means her character, “becomes very haunted by sounds that not don’t bother other people.

“And in speaking to various different conductors, they also had it; it’s what makes them genius listeners,” the actor added. “However, to have this acute connection to acoustics can also be, on a social level, a massive impediment”.

The learnings of Leonard Bernstein also feature heavily in the film, as Blanchett’s character, Lydia Tár, is a fictional protégé of the American maestro.

To brush up on her Bernstein knowledge, Blanchett worked with conductor’s real-life associate, John Mauceri, who advised on the film. It is clear from her performance, that the American conductor’s learnings deeply influenced Blanchett’s interpretation of Lydia Tár.

“Bernstein says,” Blanchett continued, “that when you breathe in, that is the inspiration. And the exhalation is the music.

“When you’re frightened, you forget to breathe. So when I was working with my friend, conductor Natalie Murray Beale, she said ‘just remember to breathe, and breathe with the orchestra’.”

As for Blanchett’s future in conducting, while she told Lihoreau, “I certainly wouldn’t call myself a conductor” she did say that if any orchestra was ‘crazy enough’ to ask her to conduct them, “I would give it a good Ozzie go!”.

Cate Blanchett interview with El Mundo

This is google translated from Spanish to English. Original source is linked below.

El Mundo: It would be said that ‘Tár’ discusses one of the most common beliefs in a civilized society. Suddenly, art does not make us better and the most excellent art associated with classical music less than none. Is it possible to be a genius and put all that genius at the service of evil?

CB: If we focus on classical music, I think of all the hours and efforts that musicians put into their art and I don’t see a single shadow. Hers is a vocation, it is talent and it is work. With actors maybe it’s something different. External elements such as fame influence this and one could doubt them…

EM: The question, rather than discussing anyone’s merit, wanted to be a reflection on the social function of art.

CB: I think that art is a good barometer to know how a society feels about itself, with its morals, so to speak. But I do not believe that any form of artistic expression has an educational function. Art is not there to make us feel better about ourselves. It’s funny because sometimes you see the public get angry when the artists don’t say exactly what they want to hear. What I believe is that the quality of art does not depend on the moral quality of the artist. Nor his social status. Before, artists were almost destitute who needed patrons to work on their business and now many times artists are very unreliable celebrities precisely because of the power they accumulate.

EM: I’m lost.

CB: I would say, to specify, that art is a tool of civilization for human beings. But that doesn’t mean it can’t be brutal or deeply ungrateful. Art is not a mirror to show us what we want to see, but, quite the contrary, to discuss our most common and unreflected beliefs. To sum it up, yes you can be a fantastic artist and be a bad person. On the other hand, my children come to mind. They constantly ask me if this or that person is nice. But what do we mean by this word? In fact, I cross-examine them and say: “What do you mean by ‘nice’? Are you asking me if she’s nice, nice, generous…?”. My poor children [laughs]. I mean, being good or bad is subjective. Can you always be bad or good? The human being is much more complex than that and it is wrong to try to quickly reduce everything to a simple concept. That is why, I imagine, we make films like this one, to avoid the temptation of reductionism. People change, power changes us.

EM: Does it mean that certain behaviors must be forgiven?

CB: There are actions that are intolerable and that are on everyone’s mind. But when it comes to things like banning books, for example, that’s another matter. I’m more of a fan of making an effort to understand the context in which they were written, even if they are extremely unpleasant or inadmissible. They can be offensive, but let’s talk then about why they are. I am more interested in talking with people who think differently than simply telling people to shut up.

EM: Posing a situation of abuse of power from the woman’s position and not the man’s as the film does, does it count as provocation?

CB: The problem is not the men. The problem is the concentration of power and how that concentration of power is exercised. We suffer from a patriarchal society, but, God forbid, I hope we never live its opposite: a shitty matriarchal society. What difference does it make if power, instead of being concentrated in the hands of men, is in the hands of women? It’s about power, not gender.

EM: What the film tells is parallel, I won’t say similarities, with what happened around the figure of Plácido Domingo…

CB: There is no specific inspiration in a specific case. As far as the Spanish tenor is concerned, the film has been written for a long time and, from what Todd tells me, there was always a female lead. On the other hand, I am not in favor of generalizing. We often talk about big scandals like Plácido Domingo’s that have enormous repercussions on many people with a single sentence: the Domingo case. And that’s it, we air it like this. And it’s very unfair because there are so many nuances that make everything relevant that we simply discard. Talking like this doesn’t allow us to examine it and see precisely how that doesn’t happen again. The important thing is not to condemn anyone, but to see why what has happened has happened and do what is necessary so that it does not happen again.

EM: You are very cautious…

CB: I always try to be because it is rare to find spaces in the media for in-depth and nuanced debates on complicated topics. We live in a time in which we are digesting many things. Movements like Metoo or Black Lives Matter are currently in the works. And in that process there is a lot of anger, a lot of anger… Which is good to move forward, to change, but it doesn’t let you look at things with the necessary objectivity and distance. And yes, you have to be cautious.

EM: I won’t ask you about MeToo directly, but more generally, about how the position of women in Hollywood has changed in recent years. How long until this question disappears from the interviews?

CB: The problem is that perfection does not exist. Let’s say that what it is about is keeping the faithful of the scale in its place. And that is a constant struggle. For all. I am thinking, for example, of abortion, which is nothing more than the right to choose the fate of your own body. Suddenly, when it seemed like something from the past, it returns to the agenda as a political act. Well, like equality, it is a basic human right and neither one nor the other have been fully achieved.

EM: And how do you see the current position of women in Hollywood?

CB: I started making movies late, I would have been 25 years old. Then I remember thinking that in five years I would be doing something else because few women progressed much further. That has changed and the reason is simple: there are more women in charge and many more doing impressive things.

EM: What do you expect from your next job with Almodóvar? [The interview took place in Venice before the director announced that he was resigning from the project of shooting Lucia Berlin’s ‘Manual for Cleaning Women’ in English. Subsequently, Blanchett has declared that she does not give up working with the director from La Mancha].

CB: I don’t have any expectations. I know we’ll find a way to work together and I’m sure it’s going to be exciting. He is who he is because he has a very particular aesthetic and world view. But you have to take into account that he is going to work in a language different from his own and from all of his cinema. So everything changes for him: a different rhythm, a different country, a different language, different cultural references… I am aware that this is a disproportionate challenge for him.

Full interview on El Mundo

Cate Blanchett weighs in on theory about new movie Tár

Mild Tár spoilers follow.

Cate Blanchett has weighed in on an intriguing theory regarding her new movie Tár, which is expected to be a big player at this year’s Oscars.

Writer-director Todd Field’s first movie in 16 years, Tár follows the fictional classical music composer Lydia Tár (Blanchett), the first female director of a major German orchestra.

One fan of the film — reporter Joe Bernstein — came up with his own interpretation of the movie. Back in November, about a month after Tár was released in the US, Bernstein took to Twitter to share his theory: Everything that happens after Lydia enters the semi-abandoned building and gets attacked by a dog is a dream, or a hallucination of personal disgrace.

Digital Spy spoke to Blanchett herself about this theory, and the Oscar-winner weighed in with her own thoughts.

“With the playing of it, I constantly was having those two things interplaying, because I think there’s a sense of who we are or who we think we are, internally, both as human beings and as artists, actors, journalists, whatever it is that we do,” Blanchett said.

“And then there’s how we’re perceived. And there’s this strange vertiginous moment where you suddenly intersect with something you’ve said or done, and it’s been received entirely in an opposite way, which is almost a nightmarish kind of moment.”

Blanchett continued: “Then there’s also a haunting of Lydia’s past, things that she has left unexamined, lies that she’s told herself, which are perhaps more heinous than the ones that she’s told Sharon [Lydia’s wife, played by Nina Hoss] and others. “

Blanchett didn’t rule out the theory entirely, but nor did she explicitly confirm it.

Instead, the star seemed happy to tread the mysterious middle ground that the movie does as well — balancing the sense of reality with the feeling of a lack of it.

“She’s constantly keeping herself at once removed. And so these things — as she’s about to turn 50 and reach the peak of her career — these things come to haunt her in a way,” Blanchett told Digital Spy.

“So I think, I think there’s a continuing lack of reality, or a boundary, objectively.”

Speaking on the objective sense of what’s real and what isn’t, Blanchett added: “That’s part of being a strange conundrum of being alive, which happens up here [taps head].”

Cate Blanchett leads Hollywood

Interview is Google translated from French to English.

“I never wanted to have a career,” says Cate Blanchett. What I like is to experiment and travel. A scene, a good script, a good team. This is her happiness. And the secret of a model career which, from blockbuster to auteur film, has made it essential. In Tar, by Todd Field, for which she won Best Actress at the Golden Globes, the Australian plays a power-loving woman. One of those chiaroscuro roles that the actress loves. A conductor friend helped her: “I was terrified. But there are no words to describe the happiness of feeling the music rise.”

TODD FIELD WROTE TAR FOR YOU. IS IT DIFFICULT TO REFUSE SUCH A PROJECT?

Todd’s movies are so rare and special that I almost said yes before I even read anything! I have always thought that if I imagine myself playing the role that I am offered, then I should not do it. Because the result will be boring, for me and for the viewer.

There, I didn’t know how to approach Lydia Tar, she terrified me. All my work is to understand why she causes this feeling, so that the public understands it immediately. No need to know classical music, just to know that Lydia Tar excels as a conductor.

DO YOU HAVE A SPECIFIC RELATIONSHIP TO CLASSICAL MUSIC?

It moves me. I share with Todd a secret love for Gorecki, for example. And I have very strong memories with certain composers. I remember perfectly the first time I discovered the work of Xenakis, played by the Australian Chamber Orchestra, under the direction of Alex Ross. That day, it’s like something exploded in my head, it was crazy.

LYDIA TAR IS A VERY TOUGH WOMAN, WHO HUMILIATES HER STUDENTS, WHILE BEING EXTOLLED IN HER MILIEU. SHOULD WE SEPARATE THE WOMAN FROM HER ART?

You always have to put the art first. I’m not the one who burns books. There are many, many books, films, works of art, even statements that I find repulsive and repugnant. But they are also a form of provocation and invite us to position ourselves. I don’t believe in banishment as progress. What is missing in our faltering democracies is the possibility of robust public debate, the reverse of what you can see on Fox News. So, yes, I know that for centuries there have been situations where students are humiliated, flouted by teachers. But whose works I continue to appreciate.

DO YOU THINK MAN CAN CHANGE?

Yes, I am convinced of it. Look at the work that has been done on the climate since the industrial revolution! We can still reverse the trend, even if we are sorely lacking in political will. It is when we look at the “unwatchable” that we move forward. You still have to have the courage…

YOU DID DON’T LOOK UP AND TAR . ARE YOUR CHOICES POLITICAL?

I don’t see it like that. Adam McKay [director of Don’t Look Up ] chose to make a satire in order to invite as many people as possible into the conversation around ecological upheaval. Guillermo del Toro, with whom I did Nightmare Alley, wanted to talk about the notion of truth and how it can be manipulated. For this, he imagined a very dark world within a circus. As for his Pinocchio, it takes place during the war in Italy, in the midst of fascist times, when the truth is confiscated. When I sign for a film, it’s above all to work with directors. I only have a small role in Don’t Look Up, we shot before the pandemic, the film’s release was pushed back. And when it happened, it looked like a documentary! No one could have imagined its success. It is the public who sees in it a political object. Not the artist. Nothing more boring than telling people what to think! That’s why I hate interviews. We talk, we exchange and a sentence will be put in bold, translated into Portuguese or Italian to go around the world… and, in five years, people will say to me: “You declared that you were doing agit-prop . I still reserve the right to be inconsistent [She laughs.]

LIKE IN THE MOVIE… DO YOU THINK SOME IN HOLLYWOOD ARE WAITING FOR YOUR DOWNFALL?

The film is a fairy tale. There are very few women conductors known worldwide, apart from Laurence Equilbey, Nathalie Stutzmann or Armenouhi Simonian… What is interesting is that Lydia is in a period of her life where she is a bit out of time, she is turning 50 years old, she is at the top, and understands, looking down, where is the direction she will take. Athletes and artists know it: it takes courage and strength to go down the mountain and find another peak to climb…

THE OTHER PROBLEM LYDIA FACES IS POWERFUL MEN.

The system she reigns over was invented by men for men who play works mostly written by men. This world has never known any other way. Yet it is she who is there on the podium. The men who were there before her had the right to be autocrats. Not her. It evolves in a democracy, under the control of its own orchestra and an executive committee. It is something that is found in our contemporary society, not only in artistic institutions. We are all subject to shareholders. This has a real impact on the way we consume, how we behave. How many times do we say to ourselves: “I can’t do this because of our shareholders?” Or: “We have to make such a decision, but our shareholders won’t want to.”

ARE THESE SITUATIONS THAT YOU HAVE EXPERIENCED IN HOLLYWOOD?

I don’t know the answer to this question. The artists I work with have a real love for their work. I see it, I feel it. But they are also capable of self-criticism. So they are sometimes brutal towards themselves and their work. This brutality turns back on the others because they know that a lively discussion can cause the other to change their mind. This may sound rude, but if you’re worried about offending people, then you’ll never strike up a necessary conversation. How to be honest, a little harsh, while remaining respectful? It’s not always easy…

ESPECIALLY WHEN THE PROBLEM MUST BE SOLVED BY A MAN FACING A WOMAN?

We can achieve equality for a few moments. Then it tilts to one side… I would like a world that sometimes leans towards the side where all women press their weight. Just for a minute! [She laughs.] We still don’t get paid the same for equivalent work. There are many walls to break down and rebuild. It is a political fight that we must not stop waging.

SO #METOO WAS USELESS?

Look what happened in the 1980s. Women thought they had advanced in society. But in the House, in the United States, they were not equally represented. What world did we live in? We have not yet integrated all the issues of what has happened to us, including with Black Lives Matter. You have to understand everything that was said, a process is underway that should not be swept under the carpet. On the other side, the wave is so powerful that it would like to take everything in its path.

ARE YOU AFRAID FOR THE FUTURE?

I’m never really confident. I am an optimistic pessimist. I assume the worst, but I still believe that the best can happen. To answer you clearly: no, I am not someone who is afraid in the morning when she wakes up.

HOW DO YOU MANAGE THE EYES OF OTHERS ON A DAILY BASIS?

I love my job as much as I hate it sometimes. [She laughs.] I would like to run away from everyone, knowing that the upcoming project, the next film, is the perfect antidote to all the questions you may have. When you work with women like Nina Hoss or Noémie Merlant, all these doubts are swept away.

TAR ALLOWED YOU TO CONDUCT AN ORCHESTRA…

I was helped by a friend. What is fascinating is that, to prepare, you must not listen to records but hear the music in your head in order to be ready to receive the shock that the orchestra provides in front of you. And there, I experienced this power. But it’s not a film about becoming a conductor. It’s a film about the search for greatness and the impossibility of achieving it, which also shows that the personal cost can be very high.

LYDIA TAR, A VICTIM OF SOCIAL NETWORKS, IS ALMOST BANISHED FROM THE WORLD TO WHICH SHE HAD DEDICATED HER LIFE. WILL SHE STILL BE HAPPY?

She moved away from herself because she experienced shame, grief. Sometimes before you die you realize that you are not who you thought you were. It’s a great playground for an actress. There is something of the order of redemption in this descent. Kate Bush sang it in Running Up That Hill . Basically, we can all start our lives over when we’ve been through those moments.

IS IT YOUR DAILY LIFE TO ALWAYS START OVER?

Yes. Tar explains that, in your own life, you have to “know how to sublimate yourself”. It’s something I try to do. For me, a white woman, actress, privileged and healthy, it may be a little easy, but I always thought that my identity was not something static, that it was evolving, fluid . And it allows me to have different ways of seeing the world. Like Lydia who was trapped by a system created by men. In the end, his obsession is: “How will I be remembered?”

AND YOU?

Me, I don’t care. The question of inheritance is very present in art, but if you start to ask yourself the question for yourself, it is that you have the wrong conversation.

Interview from Paris Match

Interview with ABC Play

Interview is Google translated from Spanish to English.

A demanding role that, however, Cate Blanchett created naturally: if the ‘teacher’ is impeccable in her work, so is Blanchett, who learned to speak German, to play the piano and even to drive like a kamikaze for one of the scenes of the movie. All the complexity of the preparation of her character is simplicity when choosing them: originality prevails and a director is enough to ask her for something “of which he had never thought”. Like the monkey from ‘Pinocchio by Guillermo del Toro’ or Lydia Tár, present in each shot of the almost three hours of this film about the abuse of power that brings her closer to her third Oscar. She would equal Meryl Streep, although she, she says, downplaying the milestone, it’s not the awards that are important: “We have to question how we measure success.”

You learned German and to play the piano for this role, but what has been the biggest challenge of playing this genius and tyrant at the same time?

— She is an absolute master of her craft and that must be understood immediately by the public so that there is no doubt that she has the unassailable right to be in her position. But the biggest challenge is understanding someone so ambiguous and enigmatic, interpreting how hidden and distanced she is from herself. She’s someone who’s at the zenith of her career but also knows she’s coming to the end of something, so there’s a pain and a destructive drive to her that’s at odds with the amount of success she’s achieving. Creating, understanding and recreating that tension that she feels was the most difficult.

Aren’t we all, at some point, strangers to ourselves?

— Do you believe? I don’t know, I think she’s about to turn 50 and she thinks about how much time she has left. She has lost her fire, in a way, and when she sees a young woman who is at the beginning of her career come in with incredible talent, it’s like she warms her feet with that fire. She’s stuck and thinks, I want some of that fresh energy. She is a person who, by directing a great orchestra [the one in Berlin], has become obsessed with the legacy, with external appearances. When all that catches you, in the end it takes you away from your creativity.

‘Tár’ explores the abuse of power from a woman’s perspective, a twist on MeToo. Does every genius end up being a tyrant, regardless of his gender?

— No I don’t think so. Having institutional power can be a very corrupting force. Look at our leaders, they can come up with a lot of human and social ideas, but then the political process, the system itself, corrupts them. She runs a major institution, she has to report to the board of directors, to the patrons and to all the individual players who of course have gone through a much more democratic process, but Mahler and the music she plays come from a more hierarchical structure, and patriarchal. Those two things are at war. The living question in ‘Tár’ is: how do you strive for excellence? Brutally. It often has to be that way, but respectfully, trying to find a way for those two things to coexist.

There is a rather clarifying phrase: “The orchestra is not a democracy, it is an autocracy”. Are democracies ineffective against the populist threat?

— (Laughs) That phrase was actually told to me by my piano teacher, an incredible soloist who lives in Budapest. We were playing Bach and she said, “No, no, no. It is not democratic. Not all notes are important. But yes, democracy is a very fragile construction and it is not something we can be passive about. For democracy to work, the population must be committed. Democratic structures cannot be put aside because the small and destructive movements serve themselves, they are much more autocratic, intimidating, brutal and shout. They seek to destroy democracy at every opportunity, something that historically has always happened because they are based on fear, and when people are afraid, they act contrary to their best selves.

In recent years, creators and artists have been canceled due to controversial issues in their biography. Can an artistic work be separated from the controversial character of its creator?

— These are two things that can and should be evaluated. Abuses of institutional power are reprehensible and must not be tolerated. No way. But a lot of these controversies are coming to light and holding back a lot of people simply because they didn’t want to play the game. That, in my opinion, cannot be tolerated. There are great works of music, extraordinary movies, amazing works of art that have been created to advance the human experience and I would hate to not be able to enjoy them, because they feed my soul. Do I support that person’s behavior? No. But you have to discuss it. I don’t think there is a simple answer.

90% of the conducting of orchestras around the world are still in male hands. In ‘Tár’, your character achieves the unattainable. Is there fear of breaking the dynamics?

— They are afraid that things will be done differently, perhaps. The terribly seductive nature of power is that once you have it, you don’t want to let it go or share it in a matriarchal structure because people think women would behave the same way. I would love to see a matriarchal structure in action. Power can affect people regardless of their gender and, less and less, but it is still a political act for women to get on the podium.

Do you share the rejection of inclusive language with your character?

— It is not a political statement, but I prefer to be called an actor than an actress, it puts me at the same level as men, although they do not pay us the same or treat us the same.

You are 53 years old and still on the front line. What is the secret to surviving a world so unforgiving with women when they have a birthday?

— “You wouldn’t mention Bradley Cooper’s age or Sean Penn’s age.” There you have it. That question says it all, doesn’t it?

Last year you received the first international Goya, has Spanish cinema influenced you in any way?

— Of course, but also Spanish-speaking directors. They broaden the sense of what is possible in film, including different color palettes and narrative rhythms. If you’re always working with people who look like you and sound like you, it gets all monotonous.

Full interview on ABC Play

Quand Cate Blanchett nous parle de Noémie Merlant… ????

"TÁR" de Todd Field, au cinéma le 28 janvier. ?

— https://t.co/5HiZ9VYSab pic.twitter.com/AMATeWgE0i

— SensCritique (@SensCritique) January 21, 2023

Cate’s glam team:

Make-up by Mary Greenwell using Armani Beauty products

Hair by Robert Vetica (Los Angeles) and Nicola Clarke (London)

Styled by Elizabeth Stewart

Accessorized by Louis Vuitton

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?)

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?) The Seagull (2025)

The Seagull (2025) Bozo Over Roses (2025)

Bozo Over Roses (2025) Black Bag (2025)

Black Bag (2025)  Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)

Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)  Disclaimer (2024)

Disclaimer (2024)  Rumours (2024)

Rumours (2024)  Borderlands (2024)

Borderlands (2024)  The New Boy (2023)

The New Boy (2023)