Hi, Cate Blanchett fans!

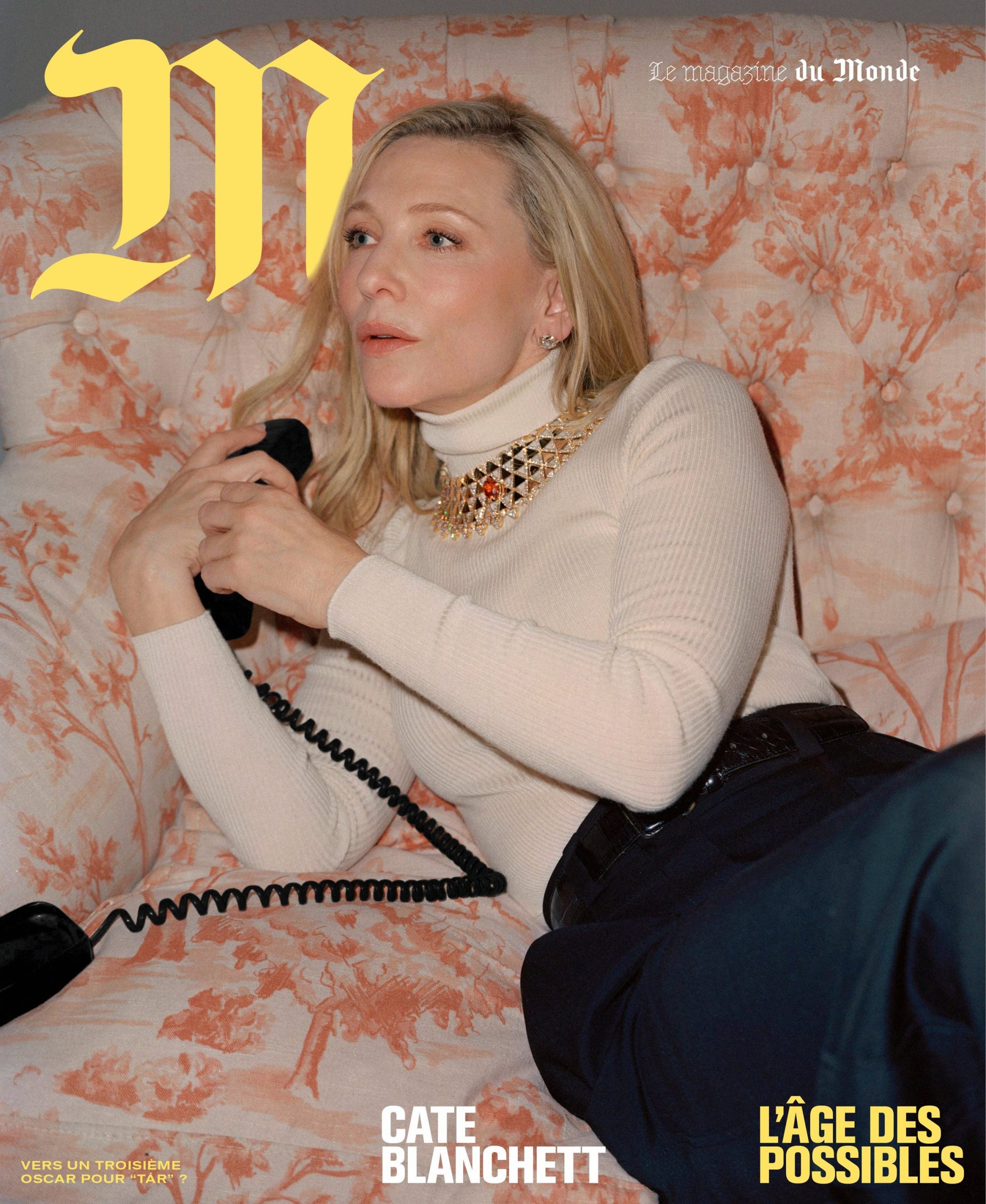

Cate Blanchett is on the cover of Le Monde M Magazine. She is also featured on other French and Spanish magazines. Unfortunately we could not find link where to purchase them online. The magazines are available on newsstands in France and Spain.

Focus Features released a new conversation with Cate, Todd Field, and Nina Hoss which was moderated by Bradley Cooper. There are also featurettes centering on Lydia Tár and Sharon Goodnow.

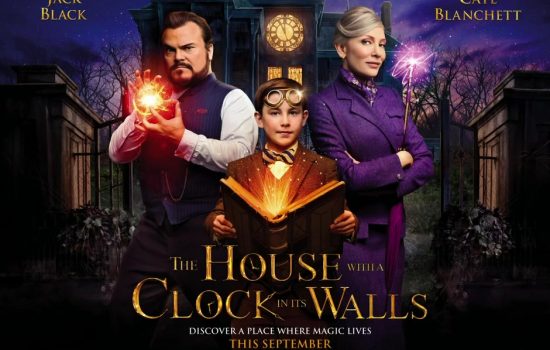

Last Thursday, Cate was spotted in her Lilith costume outside the studio lot where Borderlands is doing reshoots.

— Elle Brasil

To play the fictional character, the first conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in the plot, the actress studied piano, German and conducting. Even as an eight-time Oscar nominee, Cate Blanchett, she had doubts that she would realize it. And Lydia Tár helped to overcome them. “You can think what you want about her, but Lydia is fearless,” said the Australian actress in an interview with ELLE via videoconference. “Not that she isn’t afraid of herself, of her past, of being exposed. But still she climbs the podium and fights for what she believes in. That creative ferocity gave me a lot of courage.”

“Lydia didn’t have many female role models in her position. She drew on the examples of male conductors,” said Blanchett. But she also believes that power can corrupt both men and women. “We often feel uncomfortable when women exercise their power in a firm way. In general, these women are seen as unfeminine or difficult to like,” said the actress.

This is a controversial point. We all know that there are many allegations of sexual abuse, including in the world of classical music, and all the accused are men. In general, whites. Placing a lesbian woman in that position has generated criticism of Tár , such as conductor Marin Alsop, who said she was offended by the feature, described by her as “anti-woman”. Director Todd Field explained her choice. “We are used to men behaving badly because no one else wielded power,” he said in another interview with ELLE. “But I am interested in the question of power. And Lydia being a woman and a lesbian allows for an abstraction so that we can be more engaged in examining power and how it works.”

— El Diario Montañes

– Is it true that you learned Spanish with the Rosetta Stone method during the pandemic?

– Yes. It was one of those things that I always wanted to do. My Spanish lessons were taken ‘online’ around 3 or 4 in the morning, so I didn’t remember much the next day and had to repeat them, ha ha.

– Who are your favorite Spanish authors?

– I love to read, but, if you allow me, I have to say that Spanish films have been a great influence and a source of inspiration. Obviously, Almodóvar and Amenábar, but also other Spanish-speaking filmmakers like Guillermo del Toro or Alfonso Cuarón, with whom I’m working at the moment. Spanish culture is fascinating and I feel a synergy with it, I am very interested in its narratives and its stories.

– ‘Tár’ reveals the constant dilemma between art and the artist, I wonder if we should criticize the artist for their work or for character defects.

– ‘Tár’ is set in the world of classical music, a world in which people firmly believe in talent to be able to live, although what happens in the film could easily happen in the banking sector or in the world of architecture or engineering. It is about power and the dynamics of abuse of power. I believe that the separation between the artist and art is not necessary, but rather the separation of power in general. We do not judge, we separate the actions of people who behave as humans and how to do that separation as artists. We delve into a gray area.

– Artists and actors must be responsible for their content.

– An actor, an artist, has a very public profession, so it is up to us to realize that we have positions of influence, even if it is in a small way, but this film also speaks to society in general.

– Do you think it is important to show the public the abuse of systemic power? We are seeing him in several movies: ‘She She Said’, The Menu, ‘The Triangle of Sadness’, ‘Tár…

– I think it is important to talk about it in detail. I have realized that there is no paradise on earth. Human beings have flaws, but that doesn’t mean we don’t try to reach a better state than we have. We are responsible for improving. We must create a more inclusive state than we have now. There are many themes represented in the cinema, but there is not a single film that says that inequality is not bad. That is something indisputable and we know it. That’s not a dramatic premise. It is much more interesting to say: we know that there is a systemic abuse of power, but whoever is involved in keeping these structures alive is not necessarily the so-called power, because power is much more fragile. That’s why I love ‘The Wizard of Oz’: there was a white man behind the curtain, you just had to draw the curtain and analyze it. We have to talk about it in detail. ‘Tar’ does not allow the public to sit down and walk away with a single analysis. The people aren’t good or bad, and the movie doesn’t work on that level. This is a complicated narrative, a challenge, but it excites me and I hope that the public leaves the theater with the mere idea of ??seeing it again, because a lot happens within the story to process it in a first viewing.

-‘Tár’ is Todd Field’s first film in 16 years, he wrote the role specifically for you. How do you feel about it?

– I feel honored in every possible way, since he is a wonderful director. I am very grateful that he thought of me for this role. When he sent me the script, I realized that I had never read anything like it. I would have to say that I experienced ‘TÁR’ even before I got involved in the project because it’s a different script. I had never read anything like it. And I think the movie that Todd has made is unlike any other movie that Todd has seen. Fortunately, I didn’t know that he had written it for me before shooting started because I don’t know if that would have influenced me in a positive way.

– Are you interested in the world of classical music?

– As a child they took me to concerts and I learned to play the piano, but I gave it away. I was much more attracted to dance. Dance, like music, dispenses with language, and I’m always very grateful to a movie when you don’t have to talk, which of course was not the case with this script. But music is often the starting point to unlock the atmosphere in which a character lives, or the spirit of a character. I’m always happy when I can find the beat or the song that speaks to the soul of the character.

– How did you prepare to play an orchestra conductor?

– I asked a friend who was the center of space in an orchestra and she told me that she is the director, because if not, you don’t have the perception of space. If you don’t occupy it, the public doesn’t follow you, they don’t know where to look or whether to take you seriously. I have to be honest, on one hand I was terrified like never before in my life. We were in the middle of the pandemic, the musicians had not played important works for a long time and, as if that were not enough, the first time I raised my arm to set the rhythm for the musicians I did it a little out of time. But then, I realized that they needed me and I needed them desperately, and that somehow the music would flow. I learned the gestures and I can’t express how wonderful it is to feel how the music flows. Becoming a conductor, even if it was fiction, has been a wonderful experience.

"I put the child lock on so there was no escape" ?

Cate Blanchett's driving while filming Tár sounds INTENSE ??@jodiepresents speaks to Cate and Nina Hoss about the Oscar-nominated film.

Watch more on #TheEdit on @BBCiPlayer now. https://t.co/eyqu6WCq7B pic.twitter.com/iOEMHEcNDg

— The Edit (@bbctheedit) January 26, 2023

Google translated interviews. Click on the thumbnails for full interview.

PREMIERE: Did you know each other before working on Tár?

CATE BLANCHETT: We knew each other, but the big question is when exactly we met. Our opinions differ greatly on this subject! In my memory, we met a very long time ago. The very first time was in Los Angeles, and I had an appointment with a director named Todd Field…

TODD FIELD: Stop it! It’s wrong!

CB:.. about a project that I won’t name. A dinner where he barely spoke to me and I walked out of it thinking, “Well, that guy thinks I’m an idiot.

TF: Anything!

CB: Anyway. Then we met again for a project that Todd was working on about ten years ago [a political thriller he had co-written with writer Joan Didion], which almost got done and then finally didn’t.

TF: A wonderful encounter.

CB: This time, yes!

P: Todd, you wrote Tár for Cate Blanchett?

TF: Absolutely.

CB: You wrote it first and then you said to yourself that I could play it, right?

TF: No, no, I wrote it for you. I had never done this before, but this time, as I knew quite quickly who the character was, I immediately saw her face – yours, in this case. Before I even got down to actually writing the screenplay, I put your name down on paper. And every day, when I arrived at my desk, I said, “Hello, Cate. “You never answered anyway…

CB: I still resented you for the way you treated me the first time!

P: Cate, so you didn’t know that Todd was writing this film for you…

CB: Not at all. I only knew when Hylda [Queally], my agent, because of Todd had a car accident…

TF: A long story…

CB: So Hylda called to tell me that Todd had written a script and that I had to read it right away. And Hylda doesn’t say that often. I usually read slowly, but I devoured this one. I read it once, then immediately reread it. It’s interesting, because many people who discover Tár tend to say when they leave: “I want to see it again. The film is so rich. And very rhythmic. The dialogues are full of notions unknown to ordinary mortals, I don’t know when reading the script certain conductors or certain musical forms whose characters speak, lots of references passed over my head, but we go beyond that very quickly and we let ourselves be overwhelmed, because the whole is governed by a rhythmic sense that carries everything.

P: Is this film which talks about the power enjoyed by some recognized artists necessarily had to be an orchestra conductor? Or could it just as well have been about, say, a filmmaker?

TF: Why not, but then it would have taken place in another era, perhaps that of the studio system, and would have involved directors like John Ford or Howard Hawks. People who had contracts with the studios, at a time when things were more institutionalized for directors. You have to understand that the character of Lydia Tár sits at the top of the music world. She conducts a leading German orchestra, which places her in a line that includes von Karajan, Furtwängler, Bernstein… A line that can be traced back to Mozart. Conductor, if you are accepted by the musicians you lead, it’s a position you can hold for life. A film director sees his rating and his position change constantly. He shoots a film, then it stops, and he shoots another, then it stops, etc. In a way, he always starts from scratch. Lydia Tár has been at the head of this power structure for seven years. It’s very different.

CB: One of the differences between the world of classical music and that of cinema is that the careers of actresses, actors or even filmmakers are often described as due to luck, favorable circumstances, business connections, etc. Classical musicians owe everything to the thousands of hours they have spent mastering their instrument. They are not chosen by chance to join an orchestra, or to conduct an orchestra.

P: It is a question of excellence.

TF: It’s almost quantifiable.

CB: They are closer to the athletes, basically. Lydia Tár is at the top of Olympus, and it is as if, from there, she transmits the music of the spheres to the rest of the world. She climbed this mountain, which, in the course of a long secular tradition, was built, structured and maintained in a tocratic way. But she lives in a democratic era now. And it is suddenly as if out of tune, out of time.

P: Both of you have worked with filmmakers who, like Lydia Tár, are considered geniuses. You, Cate, with Martin Scorsese, for example. You, Todd, when you played under Stanley Kubrick. Did these great masters cross your mind in any way when building the character?

CB: The only time I thought of Marty was while watching Todd work. Both know when they build their frame that there is only one place to put the camera. The mark of the big ones! And you, Todd, I imagine that if you thought of Marty, it’s mainly because you have script to give him…

TF: Ah, ah, yes, I have a deadline, I have two weeks left! [Todd Field was writing the series The Devil in the White City, produced by Scorsese and Leonardo DiCaprio, which he was to direct but ultimately gave up]. As for Stanley, frankly, no, I haven’t thought of that. There was of course a Kubrick “system”, people who worked for him, but nothing comparable to what is spoken of in Tár. At least not in my experience. He worked with a very small team, and it was very collaborative, everyone had the right to express themselves. He invited you to see the rushes with him, we could stay on set to watch him build his film… It was an exceptional working environment, the best experience I’ve ever had as an actor;

P: The film invites these parallels between conductor and filmmaker because it deals with questions – cancel culture, the fall of “problematic” artists, the separation between art and artist which particularly agitate the world of cinema. .

TF: It’s true. But we could just as well go back to the time of the Roman Senate and talk about power, about political intrigues, in terms that would not be so far removed from those of Tár. The questions posed by the film on the nature of power, on the way it is exercised and how these abuses can be judged, are in my opinion eternal. The tools we use in the film are contemporary because the action is happening today. And don’t forget that this is, in a way, a fairy tale: there is not and never has been a female conductor of a leading German orchestra… This is a character study: the story of someone who is no longer the musician she originally wanted to be, who undoubtedly had in her youth this very pure dream of expressing herself through music, but whose artistic practice has been gradually transformed by all the obligations that are its in the position it occupies today. I didn’t want to do an film on cancel culture, or any other contemporary phenomenon. It’s present in the film because it’s the climate in which we live today. But in two years, it will be something else. In two hours, it will be something else!

CB: In my eyes, Lydia Tár knows that as an artist, she is coming to the end of something. She has reached perfection. She is preparing to complete her recording of all of Mahler’s symphonies, which will be released on vinyl on Mahler’s birthday. What could be more perfect than that? What to expect after? She probably knows more or less consciously than, from where she is Olympus, again – she can only come back down. And, without recounting the end of the film, what I find noble and beautiful about her is that she decides, in order to advance as an artist, to self-destruct. She lets go — not like all those motherfuckers who cling to power until their last breath. I find it powerful and courageous. I didn’t understand it on first reading. I had seen the fall of the character, the missteps, the crash, the tragedy. But the end of the film can also be interpreted as an epiphany, a rebirth, the beginning of something again. A catharsis – without wanting to sound too pompous.

P: Todd, by the way… What if Cate Blanchett hadn’t wanted to do the movie?

CB: Perhaps you could have learned from it, I don’t know… an animated series?

TF: Um… Tiny Tar? (Laughs.) No, worst scenario would simply have gone to join my “dead letter box”. Where all the scripts I’ve written lie over the past fifteen years…

Cate Blanchett notes that if there’s one thing about Todd Field’s characters, it’s that they’re deeply human. The double Oscar winner for The Aviator (2004) and Blue Jasmine (2013) points out that, as they filmed TÁR, she felt that she was discovering different sides of Lydia’s personality. However, there was one aspect of the character that remained invariable in the actress’s mind: the feeling that she lives disconnected from herself. As we discover as the film progresses, Lydia is a person capable of erasing her past to achieve what she is after, which is the full development of her musical talent. But her way of being makes her a woman haunted by shadows that come from her past, from her own interior and from old relationships, the Australian concludes.

With her performance, Cate manages to convey the feeling that there is a train heading towards her character at full speed, and that it is going to crash into her at any moment. According to Field’s words, during the filming of TÁR, the director of Secret Games (2006) became another spectator of Blanchett’s virtuoso acting work: While we were filming, it was not easy to assimilate the magnitude of Cate’s work . In each scene, she displayed a flurry of small decisions, almost imperceptible at first glance, which later revealed themselves as key for the understanding of the character.

Field reveals that when he called Blanchett to propose the idea of shooting the scene in long shot, “She told me it was impossible, because we had to see the interactions between Lydia and the students. I asked her since the rows of chairs and the stairs in the auditorium made it impossible to use cranes or cable systems to film in a single take.” To solve the challenge, Field and his team invented a ‘filming unit’ operated by four technicians who had to take turns moving and stabilizing the camera. “If the technical part was complicated, you have no idea what it took for Cate and the other actors to participate in that highly precise choreography. It was like playing without a net,” Field says. “We reserved two days for filming the scene, and the first take we did was almost perfect, but at the last moment a technical problem ruined it! And then we didn’t get another good take until the end of the second day!”

TÁR intertwines Lydia Tár’s odyssey with a number of hot topics, from gender issues (the protagonist has a daughter with her partner, Sharon, played by Nina Hoss) to public judgments in the internet age (Lydia’s skeptical of ‘cancel culture’). However, Blanchett, who became an emblem of queer cinema thanks to Carol (2015), is reluctant to focus on the political dimension of TÁR. “The use of the word ‘important’ in relation to art makes me very suspicious. I don’t conceive artistic practice as an educational tool,” says the 53-year-old actress. “All works of art can inspire and can offend, but that is beyond the control of the creators. The funny thing is that, while I was making TÁR, I never really took into account the question of gender or the sexuality of the characters. This theme, like many others, is there to advance the plot, but what is central is the existential question. I’d like to think that we’ve evolved enough that a movie like this can be read and understood without the need to turn the genre into a headline.”

Since TÁR is a film that addresses the issue of abuse of power, it seems appropriate to ask Blanchett about the transformations that have taken place in the her industry in recent years, marked by movements such as #MeToo. “The movie industry has changed a lot since I landed here, many years ago,” admits the actress, mother of four children. “I remember that, in my early days, when I made the leap from theater to cinema, my husband (theatrical director Andrew Upton) told me the following, in the most encouraging way you can imagine: ‘Make the most of this moment because you only have a five-year career in front.’ And that’s how the world worked at that time. Luckily, things have changed, and not only thanks to the work of great actresses who have conquered new territories, but also due to the efforts of men who have sided with us, such as Todd (Field).” Despite everything, Blanchett still sees a pitfall in achieving equality between actors and actresses: “It’s hard to find Hollywood actors willing to accept good supporting roles in movies starring strong female characters.”

What first attracted you to “Tár”?

I knew I would say yes to Todd [Field] even before he sent me something to read. We met ten years ago for a screenplay he was writing with Joan Didion, but the project fell through. His films are always surprising, supremely nuanced, adult, stimulating. When I read the script for Tár, it surpassed all my expectations. The technical challenge of playing a conductor terrified me, but it was only a matter of work. Above all, there was this huge and elusive character. And then the film tackles a lot of questions that Todd and I had about the creative process, inclusion, the corrupting nature of institutional power, the quest for excellence and what we can afford in its name. The more we progressed in the shooting, the more the script revealed new facets, the more I realized to what extent “Tár” was evolving towards a dreamlike part, a Tarkovskian dimension.

What do you have in common with Lydia Tár?

I do not know. People often speak to me of ambition about her with a pejorative undertone that seems to insinuate that it is an anti-feminine attribute… Let’s say that I recognize myself in her intransigence linked to the fact of leading a large institution. I experienced it on my small level when, with my husband [director Andrew Upton], we took over the management of the Sydney Theater Company: juggling the various stakeholders, overcoming the disappointments that your choosing to highlight someone arouses in others… The balance is fragile and difficult to find. I also understand Lydia Tár’s exaltation when she feels carried by the stage, her desire to commune spiritually through her art. And his pain when you take all that away from him.

Have you, like Tár, ever misused your power?

I don’t know, it’s not for me to say. People sometimes perceive us differently from what we think we are sending back or misinterpret something and take offense. What attests to your character is if you show yourself to listen and try to smooth things over or if you calcify yourself and adopt a defensive posture.

Tár deals with the influence of social networks, cancel culture and political correctness…

This is just one of the many facets of the film. Any story, film, or novel created today will be judged through the prism of these movements. But I’m not on social media, I don’t live in that world. I am well aware of their power, of the important role they have played in giving voice to people who did not have it and uniting them. Social media is a strength when used wisely.

What do you say to the conductor Marin Alsop, supposed model of your character, who criticizes the film for making her an “aggressor” and says that she felt offended as a woman, conductor and lesbian?

My character is not based on anyone specific. I fed her with so many different conductors: I spoke to Simone Young. Nathalie Stutzmann, Gustavo Dudamel, among others. Their reactions to the film were very diverse and they saw many other things in it. I also delved into novelists, listened to interviews with Susan Sontag, Antonia Brico… Tár does not deal with conducting, nor even with gender or sexual orientation, these are just aspects of the film that should not be taken literally. I have the deepest respect for Marin Alsop, an outstanding musician and pioneer in her field. Aiming for her was not our intention.

Speaking of well-meaning, do you feel its impact in the scenarios that are offered to you? Films like “Tár”, complex and ambiguous, aren’t they more and more rare?

Bold movies are still being made. The species in danger, in my opinion, are the cinemas where these films are screened, the comfortable rooms with good quality equipment. Often, the seats are terrible, the sound does not work well… Cinema, if you really make it, is a very rich medium capable of offering the public an experience that marks them for a long time. The sound work in Tár is very elaborate. Just like the ideas it conveys. But if you watch it at home, on a small screen, you will only appreciate 15%. The biggest challenge today is for theaters to survive and for people to be able to continue to see films in the right conditions.

Where is your project with Pedro Almodóvar?

We’ve been talking for years about working together. We were supposed to do it on the adaptation of Lucia Berlin’s book, “A Manual for Cleaning Women”, but Pedro does not feel comfortable with English. The film will not be directed by him. We are thinking about another project.

I would like to talk about your political and social commitments, which this film also reflects…

My work has nothing to do with politics. The reactions it provokes can be politicized but I see it as an act of understanding, an instigator of debate. The artist must be inconsistent, provoke… and entertain.

Let’s go back to your commitments. You support a large number of causes.

They are all linked. We cannot sound the alarm about the displacement of populations and refugees seeking asylum without linking them to the climate crisis. We cannot talk about systemic inequalities, abuse of power and domestic violence without measuring their impact on displaced populations. It’s all part of the same problem: the issue of human rights. Which is not political but is constantly politicized.

You host a podcast on climate change, “Climate of Change”.

I despaired of what was happening to our planet, and during the first lockdown, my husband and I chatted endlessly with one of our close friends, Danny Kennedy, a start-up entrepreneur specializing in sustainable development. Talking to him was good for me because he is aware of all the initiatives underway. My husband threw at us, “You should do a podcast!” There you go. We have already recorded two series and we should produce a third on refugees linked to the climate crisis. In particular the fate of women and children. The subject concerns me all the more since I have four.

Making films is not very eco-compatible. Have you changed your way of approaching the job?

I keep worrying about it in my production company. Because it all starts with everyone’s effort. The quantity of travel, waste, hardwood and plastic consumption that filming represents is enormous. We are working with actress Fran Drescher with the Screen Actors Guild [the union for American actors] to change habits. It has to start from the top, from the production methods, from the way each film is conceived. When my husband and I took over the Sydney Theater Company in Australia, one of our first steps was to go green. We chose suppliers of materials in rocky substrates – which transformed the aesthetics of the decorations, had solar panels installed to free ourselves as much as possible from the electricity network… It is now in the DNA of the place. And people come to work there in a better spirit. The creation that ignores the waste of resources is death.

What inspires you about the future?

I imagine that the projects you choose do not go against your values and your political ideas? Tár attracted me because it’s a refined, nuanced film, and you don’t see much of it anymore. I wanted to be part of the debate that provokes. But never, never will I seek to impose my ideas

to the public or to tell them what to think. John Cusack once said to me in a joking tone: “I couldn’t play a character who has never listened to Bob Dylan. I listen to Dylan all the time but I don’t agree with him on this point.” Each of my roles was an opportunity for me to approach another way of thinking and to seek to understand it. I am immensely concerned about how little time we have left to reverse the course of climate change. And by those evil forces, mostly male, who cling to power for personal gain under the guise of defending ordinary people. I am very worried about democracy and education. I sense a concerted will of these same evil forces to keep people in ignorance. I recommend a fabulous book, The Dawn of Everything (by David Graeberg and David Wengrow), a world history focused on Western colonization. It is uplifting and very inspiring.We saw you recently, with other artists, in a video, holding up a #StopExecutionsinIran sign.

With our production company, we are working on the film by a young director, Noora, around her experience as an Iranian exiled in Australia. There is a need to bring these topics back to one person’s experience, to concrete examples, as I do in my work with the UN Refugee Agency. People are so quickly reduced to numbers. Especially since the horror they endure is difficult to apprehend when one is outside them, one can easily feel helpless. The international movement in support of Iran keeps hammering it: “Say the names.” One of the memorials that struck me the most is in the Jewish quarter of Prague. On the wall of the synagogue are written in small letters, blue and red, the names of each resident of the district displaced or killed in a camp. Added to this is a ritual of intoning their names, as if to keep their spirits alive. Each of these names could be yours or mine. That’s kind of the idea that I try to inject into my work. Be careful, far be it from me to draw a parallel between my profession as an actor and these humanitarian crises. I’m just saying approach each role by trying to dig a path between the character and the spectators so that they recognize themselves in an experience that is not their own.

There are the gifted people and there are the others. Cate Blanchett is convinced to do part of the second category, of those who, because they have no particular talent, let alone genius, must work intensely, laboriously. This impression, she does not take offense and faces it with serenity. And, by a mirror effect, she is passionate about gifted people. Because they are better than her, in her eyes, able to teach her a profitable lesson, and they are also more fragile. This is what strikes her when she thinks back to her character as Lydia Tár, the conductor of a great German symphony orchestra, at the height of her career, in the midst of preparation for a highly anticipated performance of Gustav Mahler’s 5th Symphony. . To interpret the main role of Tár, the new film by Todd Field, the Australian actress imagined, as usual, biographical elements absent from the script. Details, visible only to her, that she always writes down on a sheet of paper. As if to materialize her work, since, for Cate Blanchett, acting is above all writing.

With Todd Field’s film, which could earn her a third Oscar in March, Cate Blanchett seems to have taken another step further, as it appears that only a very talented actress could lend her face to such a complex character.

“I could tell you that I became an actress, because I was destined for it, that everything, or almost, led me there,” says Cate Blanchett. But no. Her journey might have taken the form of a very elaborate journey if she had been in the category of gifted people, those who have no choice but to embrace the career for which they are destined and possess nothing but their talent. She assures him, for her, “none of all this”: “My parents did not come from the theater world. There is no musician or painter in the family, my father, American, worked for the United States Navy, my mother taught high school. She grew up in the suburbs of Melbourne, far from any idea of embarking on an artistic career. “It wasn’t until university that I was suggested to go to drama school in Sydney.” The scene was then a refuge for the one who was not comfortable in her own skin, who found herself too big, not suited to others. “If I went to the theater, it was for its circus family side. So, you see, it all happened in spite of me rather than by any plan.”

In Cate Blanchett’s mind, Lydia Tár would be the only child of deaf parents, “which, in turn, affects the way she communicates with others.” This is one of those invisible additions to the role. An attention to detail that irrigates all the work and its manufacture. In the film, the orchestra conductor changed her first name from Linda to Lydia. And that brings a mysterious sophistication to the character. “A level of refinement”, adds the actress. The heroine of Todd Field’s film suffers from misophonia, an aversion to sounds, which can place her in a state of near hysteria, where even the breath of the air conditioning disturbs her concentration, which explains, without ever excuse, his conflicting relationship to others. Like so many musicians, Lydia Tár also has absolute pitch, the ability to associate each sound with a specific note. To prepare her character, Cate Blanchett spoke with Australian pianist and conductor Simone Young, who told her that this true gift from heaven also had a price. All noises inaudible to ordinary mortals, a dog sniffing, for example, are transformed for her into so many howls.

For a long time, asking Cate Blanchett a biographical question was like trying to pull a tooth out of her. In an interview, the Australian actress could spend ten minutes explaining to you the differences in intonation between the voice of Katharine Hepburn (whom she played in Aviator) at 40, then at 60, noting that her phrasing was not identical depending on whether she was seated or standing, and whether she had preferred to find, for Martin Scorsese’s film, the way of speaking of a 60-year-old woman. On the other hand, a basic question, and not necessarily indiscreet, about her life was brushed aside. In 2003, in the benchmark program “Inside the Actors Studio”, by James Lipton, where an actor is invited to meticulously explain her work and her career, including family, she replied: “I more or less forgot my childhood. The question of who I am doesn’t interest me much. As for the link that could exist between me and the characters that embodies, it remains fortuitous and subliminal.” Things have changed. When she tries to imagine the biography of the character of a musician who maintains complex relationships with others, Cate Blanchett also relies on her own story: a father who passed away when she was 10, a mother forced to drown in the work to make ends meet and his position as second in a family of three children, wedged between his older brother and his younger sister. “My mother always wanted to be a jazz singer, so in the evening she would put on a record and we would dance,” explains the Tár star. Then she adds in the same breath, to darken the picture, because to prettify it would be to lie: “Speaking was more difficult.” As if her first year in high school had been that of silence and that she had to live with it: “There are things we should have talked about, even if it was difficult to talk about them. We did not do it. We tried. It’s nobody’s fault. Silence has settled in our home.”

Cate Blanchett likes to let her characters do the talking for her. In 2007, Todd Haynes made her an offer she couldn’t refuse: to be one of six actors – the only woman – to play Bob Dylan in I’m Not There. More precisely, the Dylan of the electric period, in the mid-1960s. The actress had already interpreted intense and difficult roles, that of a Nazi collaborator in Berlin immediately after the war in The Good German (2006), by Steven Soderbergh, about an American tourist in Morocco accidentally injured by two teenagers playing with a sniper rifle, in Babel (2006), by Alejandro Iñárritu, or even Queen Elizabeth in Elizabeth, an elf in the Lord of the Rings trilogy, she still had to play a man. “I wanted to be Dylan,” she says. Cate Blanchett knows how to place her immense resources at the service of her projects. It was necessary to rediscover the slender body of the Dylan of the 1960s, with his frizzy hair as if drawn towards the sky, this insolent pout, this extreme awareness of his talent which allows him to break everything he has built musically before, and this astonishing androgyny, and sexuality which at the time it was agreed to qualify as “ambiguous”. Cate Blanchett’s performance is unbelievable. Bob Dylan in 1965 appears in all majesty. When she learned that the American singer had not wanted to take an interest in this singular film or in the work of the six actors, she did not care. “Dylan continues on his way,” concludes the actress. “He lives in his world.”

“Time is everything. You cannot start without me. I start the clock.” Cate Blanchett then waves her hand to the attention of the public, to show her power: “Sometimes my second hand stops which means that time stops.” Suddenly the talent of this conductor is revealed, reaching the top, at the same time as the monstrosity which threatens to burst into the open. In Cate Blanchett’s eyes, it didn’t matter, there was no doubt: this desired transcendence, this need for domination could only be admirable and atrocious. “How far can you go when looking for excellence?” asks the actress. “And to add:” It is as if the extraordinary personality of this immense artist had taken precedence over the music in the service of which she should nevertheless be. When she speaks, Cate Blanchett continues to take notes, to find the right word or not to let slip an idea. Suddenly, a key element about his character comes back to him: “I was going to forget something. This woman is about to turn 50.” A psychological milestone that the 53-year-old actress has already crossed herself. “Am I at the end of my career or in the middle of my career?” at her age, for an actress, in the cinema, one speaks more easily of the end of a career. It’s not absurd. “Look, these last few years, I had to put priority on my family, the Sydney Theatre Company, which I looked after with my husband, Andrew Upton. Tár talks about the time you have left. And the time, I don’t have that much left.”

The younger Cate Blanchett had the privilege of seeing Mikhail Baryshnikov on stage at an older age. The Russian dancer exiled in the United States was no longer in full possession of his physical faculties. Except that experience and mastery enabled him to perform movements that were previously impossible for him. “I think the most magical moment on stage is when a dancer jumps. We do not know if it rises or if it will fall, it is a moment of suspension. I’m so looking for that feeling, that moment when, although it’s impossible, you feel like you’re flying.” The profession of dancer, in her eyes, goes beyond that of actor. “If I had to do it all over again, I would look more towards dance and Sylvie Guillem or Martha Graham. With them, language is reduced to a gesture, you no longer intellectualize things.” The Australian actress remembers Mikhail Baryshnikov wearing a black turtleneck on stage. Although he no longer produced the miraculous leaps he once did, his black turtleneck allowed his wrists, neck and face to catch the light, he was able to play with the articulation of his fingers with such virtuosity that he gave the impression of still jumping as high as before. Cate Blanchett therefore lives for this “Baryshnikov moment”, this period of life when experience allows not only to hide the pangs of age, but also to realize what was impossible to accomplish when one was older. “In Tár, my character gives a master class at Juilliard. She tells a student orchestra conductor: “You haven’t earned the right to abstraction yet. It’s like poetry, the haikus take on more meaning if you’ve written much longer poems before. That’s what I like with Tár, it’s a role I can play since I’m this age. A younger actor might have said no.”

With age, the actress has created new routines. Like walking. In her mansion in the south-east of England, she regularly takes her dogs and children on board: “And if we went for a walk today?” Andrew Upton, her husband, is urged to follow suit. The walk generally extends over about fifteen kilometers and the director always tries to shorten it. But all take the necessary time. If it is unthinkable to compromise on the length of the path, it is possible to negotiate the route. Not far from the couple’s house is the former home of Charles Darwin. It was on a seaside path that the scientist developed his famous theory of evolution that fascinated Andrew Upton. “To give you an idea,” adds Cate Blanchett, “Darwin walked as many kilometers on this perimeter as to travel the globe.“ Before setting foot for the first time on this “path of thought”, as the scientist called it, the actress and her husband said to themselves that it must be very long, since the thinker paced every day without ever get bored there. But it’s actually a tiny path. “It looks like the garden of a suburban house,” continues the actress. Was that his daily walk? It is however in this very small perimeter that Darwin built up his research. “I think back to this principle of Buddhist philosophy: to dig deep into an idea, you don’t have to go very far. The great musicians, for example, interpret at regular intervals, throughout their career, the same piece, because they always find a new dimension in it.” This approach now occupies a good part of the thoughts of the actress: “And if I too dug the same idea, but always deeper? What if, at the end of this quest, another idea pops up? And, at the end of this idea, the prospect of being in mid-career?” And therefore to still be able to do so many roles, so many films. After all, Cate Blanchett is only 53 years old.

Borderlands Reshoot

Cate Blanchett was spotted in Los Angeles last week for Borderlands reshoot.

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?)

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?) The Seagull (2025)

The Seagull (2025) Bozo Over Roses (2025)

Bozo Over Roses (2025) Black Bag (2025)

Black Bag (2025)  Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)

Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)  Disclaimer (2024)

Disclaimer (2024)  Rumours (2024)

Rumours (2024)  Borderlands (2024)

Borderlands (2024)  The New Boy (2023)

The New Boy (2023)