Hi, everyone!

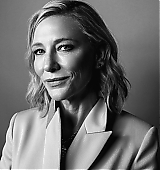

Cate Blanchett attended a Q&A after a private screening of TÁR in London last Thursday. Check out the interviews that have been released the past days. There are also new interviews within the magazine scans.

There are only three films in the history of the motion picture industry that have ever achieved unanimous consensus with The NYFCC, LFCC, LAFCA, and The NSFC. Now there are four.#TÁR is the best picture of the year. pic.twitter.com/4UDWOQiPk5

— TÁR (@tarmovie) February 12, 2023

? The ever fabulous #lydiatar herself… So good to see #Tar on the big screen, and hear from the brilliant #CateBlanchett who has created an unforgettable #MeToo movement role, filled with ambiguity & many many points to ponder. ? @universaluk ? #Mayfair #London pic.twitter.com/pOqOj8ECjR

— A$hanti OMkar ? London, She | Her, Film, TV Critic (@AshantiOmkar) February 10, 2023

Watch on TikTok

Y un día… ¡HABLAMOS CON CATE BLANCHETT! ?????? pic.twitter.com/24kyGYMU6J

— Cinéfilos (@cinefiloos) February 12, 2023

When Cate Blanchett was a nine-year-old attending music classes in suburban Melbourne, it was her teacher, Mrs McCall, who first noticed where her talents lay. “I remember one day, I was playing the piano,” she recalls, “and Mrs McCall put her hand on my hand and said, ‘You haven’t practised, have you?’ I just burst into tears and said, ‘No, I haven’t.’ And she said, ‘I think we should stop, because I don’t think you want to be a pianist, you want to be an actor.’”

Though she was disappointed at the time, Blanchett now realises how perceptive her music teacher was. “She would have these concerts and she instinctively picked up on how I would just come along and act the part of a musician.”

One cannot help but wonder what Mrs McCall would think of Cate Blanchett’s leading role in Tár, one of the most talked-about and argued-over films of recent times. In it, Blanchett gives her most powerful performance to date as an imperious classical conductor, whose public fall from grace sabotages her stellar career just as it approaches its apex: a much-anticipated performance of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony.

When Blanchett first read writer-director Todd Field’s script, she said recently, “I inhaled it.” What was it, I ask, that so excited her? “One of the dangerous and alarming things about the film is that it does not invite sympathy or offer easy solutions,” she says. “No one is entirely good, and no one is entirely innocent. It’s a very nuanced examination of the corrupting nature of institutional power, but it’s also a very human film because at the centre you have someone in a state of existential crisis.”

Writing in the New Yorker last year, Richard Brody set a high bar for aggrieved outrage, lambasting almost everything about the film, but particularly what he saw as its loaded ideological thrust.

He took aim at one scene, in which Tár rounds on a nervous young music student, Max, who identifies as a “Bipoc pangender person”, and declares that he is “not into” Bach because of the composer’s misogyny. Depending on where you stand, the scene dramatically condenses or renders as cliche the current generational cultural battleground in which the earnest certitudes of identity and gender politics threaten the once-sacrosanct status of canonical – white, male, heterosexual – culture. For Brody, it epitomised “a regressive film that takes bitter aim at so-called cancel culture and lampoons so-called identity politics.”

I ask Blanchett what she makes of such responses, if indeed she reads them at all.

“I have been very reluctant to talk about the film,” she says, “partly because it is so ambiguous and I don’t want to define it for anyone. I also think it’s hard sometimes for journalists, because they see so many films and then they have to give an immediate opinion. A lot of people who have sat with it or watched it again have expanded their perception of what the film is. Not only is the character very enigmatic, but the facts of what has transpired, if you want to call it the plot, are very vague. In a way, the film is a Rorschach test when it comes to the kinds of judgments people make in terms of the information that is alluded to, but never confirmed.”

I am speaking to Cate Blanchett via a video call to Los Angeles just two days after her portrayal of Lydia Tár won her the best actress award at the Golden Globes. It is the third time she has triumphed in that category. A few weeks after we speak, she will receive her eighth Academy Award nomination and, should she win – she is currently favourite – will become only the third actress in history to have been awarded three or more Oscars. (The other two are Frances McDormand and Katharine Hepburn.)

“Awards are lovely,” she says, when I ask her about her decision to attend the London premiere of Tár rather than the Golden Globes ceremony, “but we thought it was important to support the film’s European release.” The context for this may be that, although Tár has provoked a deluge of critical coverage, it has not performed that well at the American box office, being closer in that sense to the unapologetically cerebral films of European auteurs like Michael Haneke.

Even on Zoom, Cate Blanchett has presence. Perched at a table in an expansive, minimally furnished room in Los Angeles, her blond hair tied back and her face framed by a pair of large, thick-rimmed designer spectacles, she evinces an air of stylish cool but turns out to be refreshingly down-to-earth. When animated, she waves her arms expressively and, in repose, has that loose-limbed way of arranging her body dancers often have. “It’s a strange thing coming to discuss something that one has made,” she says, “because you’ve worked from a different kind of intelligence in your frontal lobe. So you’ll have to excuse me if I don’t make sense very often.” The opposite is, in fact, the case: she is thoughtful and fiercely articulate throughout.

Lydia Tár is not the first unsympathetic character Blanchett has portrayed – her role as the ultra-conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly in the TV mini series Mrs America immediately springs to mind – but her sustained, pitch-perfect performance propels Todd Field’s cerebral, provocative film and may well come to define her as the most gifted – and risk-taking – actress of our time. She is onscreen for almost every scene in the film’s two-hour-plus duration, brilliantly capturing the dissonant, domineering personality of a narcissistic genius whose utter self-centredness, amplified by fame, privilege and a luxurious lifestyle, has inured her to the feelings of others.

“I think she is one of the greatest practitioners of the art that has ever lived,” says Field, when I speak to him on the phone in Los Angeles. An actor turned director, he wrote the script specifically for her, and insists he would not have made the film had she not agreed to play the part. “It’s one thing to have a work ethic and incredible discipline, but that does not always translate into great acting, whereas her ability is in many cases almost supernatural. I don’t know where that indefinable gift comes from, but actors who have it do not come along very often.”

In preparation for the role, Field tells me, “Cate did something I have never seen any other actor do: she memorised the entire script – her lines, everyone else’s lines, even the script references. She did a deep dive.” Blanchett also learned German, took piano lessons, studied online masterclasses by the great Soviet conductor Ilya Mussin, and sought out as many performances of Mahler’s Fifth as she could.

“I can’t tell you how many conductors I watched,” she says now, “and they were all so idiosyncratic! Some are rigid beaters, some not so clear beaters at all, but very, very expressive. Some barely move and some jump up and down on the podium. I realised, through watching them, that there was a freedom to make it my own.”

Field, whom she describes as “the master of authenticity”, insisted that she should actually conduct the Dresden Philharmonic in rehearsals for Mahler’s Fifth while the cameras rolled. What was that like? “Terrifying. Absolutely terrifying,” she says, laughing. “I began by asking for their patience and said in my terrible German, ‘I’m an actor playing a musician and you are musicians playing actors.’ We had their trust early on and we found our way together.”

Blanchett’s immersion in the role is total, and the sheer force of her presence drives the narrative as it moves from a realist, almost documentary style to something altogether stranger as Tár’s once-assured sense of herself unravels. In a celebrated career, Blanchett has tackled many demanding parts, from the title role in her breakout film, Elizabeth (1998), to her acclaimed performance in Carol (2015), Todd Haynes’s lush tale of forbidden love. Did any of her previous parts prepare her for the sustained intensity of this role? “Well, I’ve had the good fortune of working with extraordinary directors on really interesting films, but I’ve never had such a deep and rich collaboration. There was something really immersive about this one, beyond anything I thought possible outside the theatre. I’ve never encountered a story like this. Or a character like this. She inhabited my dreams.”

At her worst, though, Lydia Tár’s behaviour is the stuff of nightmares. The terms most commonly used to describe Tár in even the most positive coverage of the film are “monster” and “monstrous”. Does Blanchett think of her in this way?

“Well, for me personally, the world in which we live is monstrous,” she replies. “It enables, invites and often enshrines and rewards monstrous behaviour. It’s very easy to say she is monstrous, but the film is much more ambiguous than that. It begins with a closeup, not on a person, but on a mobile phone, an instrument of easy opinion and gossip as well as information. I’m not demonising it entirely, but that is the world in which we live. The character, on the other hand, is enigmatic. In a way, I felt that I was playing a state of being, or a set of atmospheres, as much as I was playing a person.”

That, however, is not how Marin Alsop, the world’s most celebrated living female conductor, saw it. Like the fictional Lydia Tár, Alsop is a lesbian married to a classical musician, with whom she has a child. And like Lydia Tár, she runs a fellowship for young female musicians, and was mentored by the great American conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein. In a recent interview with the Sunday Times, Alsop said the film-maker’s decision to “portray a woman in the role and make her an abuser” was “heartbreaking”, given that there were “so many men – actual documented men – the film could have been based on”. She was, she said, “offended as a woman, as a conductor, as a lesbian”.

When I mention the interview to Blanchett, she responds calmly. “For me, what is wonderful about the film, and sophisticated about the narrative, is that it examines power in a way that is genderless. Nothing is drawn. It’s not just a film about a female conductor who falls from grace, it’s about something much less political than that, even though the position she finds herself in is incredibly political. I think it’s a very complex film and one that will stand the test of time. And it’s certainly not a literal film, and to endeavour to interpret it literally is, I think, a misdirect.”

Blanchett describes Tár’s shape-shifting narrative as “a kind of haunting”, which certainly applies to the final third of the film, in which we experience events – and possibly imaginings – from Lydia Tár’s feverish and fragmenting point of view.

“There is an elusive, existential quality to it that is part reality, but an even larger part the nightmare into which she is descending,” she says. “I think she is very haunted by things she has not had the courage or the ability, or the time, or the inclination to look at and examine.” She pauses for a moment. “It’s a tricky thing when you are playing someone who is very hidden from themselves, who has been so focused on, and devoted their life to, the pursuit of excellence, who suddenly puts her head up and realises that she is not perceived as the person she thinks she is. Or that she has caused damage to people. She has been blind to it because she has been so enraptured by what’s in front of her.”

Despite – or perhaps in part because of – the strong reactions it has provoked, Tár is a film that has creatively energised Cate Blanchett. “I’m still processing the experience,” she says, “because it has tipped me off my axis in a wonderful way.” Working with Field, she says, she experienced the sort of freedom she usually only finds on stage. “The process was such that we were not entirely sure exactly where we were going to end up. And that was thrilling. It felt much more dynamic, and much less like having a safety net. You don’t get to work in that way very often in cinema, because cinema doesn’t often explore the non-literal end of its capacity.”

Blanchett’s roots are in the theatre and one senses that it is the visceral nature of live performance that still engages her most. Her first serious role, aged 23, was in a Sydney Theatre Company production of David Mamet’s Oleanna in 1992 and, later that same year, she was critically acclaimed for her performance as Clytemnestra in Sophocles’s Electra. “The first time you experience that form of catharsis,” she says, “you are at the centre of something that you keep wanting to get back to the centre of.”

Thirty years on, she is “talking” with the British theatre director Katie Mitchell about a possible stage adaptation of Lucy Ellmann’s contemporary modernist novel Ducks, Newburyport, which is an epic, stream-of-consciousness narrative comprised of a single sentence. “In a way, it’s a bit like Tár,” she says, “because the audience thinks I have got to understand every single sentence this person is saying. Whereas for me the book, like the film, makes rhythmic sense as much as being deeply painful and funny and unsettling.”

Blanchett’s schedule is, to say the least, packed, and her work rate phenomenal, even by the standards of Hollywood acting royalty. “For me, I suppose, it’s the process rather than the outcome that’s important,” she says, when I ask what she considers her pivotal roles. “It’s all about the quality of conversation that I’ve been part of. I realised very quickly that the opportunities to spread one’s wings in this industry close down very quickly, because often it is such a literal medium. And so I took little parts where I could keep experimenting, parts other people didn’t want to do. People would say, ‘You have got to stop playing small roles.’ And I’d say, ‘Well, why?’ I was just interested in the experimentation of it and not building a career. I didn’t know what that was. I still don’t.”

Nevertheless, here she is, arguably the most respected – and possibly the most grounded – actress in the world. When I ask her how she deals with the other stuff that attends her calling – the celebrity, the constant attention, the adulation – she shrugs. “I don’t get bothered by it. There is so much to do in the world, and I have learned over the years to just focus on the task at hand, so if someone in the supermarket taps me on the shoulder, I’m always surprised by it. And there are a couple of films I’ve been privileged to be part of that have affected people, Carol being one of them, and I’m very always very moved by the responses.”

She gives the question some more thought and adds, “I can get uncomfortable perhaps when there’s a conflation between who I am – whoever the fuck that is – and the characters I’ve played. That is because I couldn’t be less interested in bringing the role to me. Instead, I at least attempt to rise to the occasion of the role, and with Tár that was a very big mountain to climb.”

Blanchett currently divides her time between Los Angeles, where she mostly works, rural Sussex, where she lives with her husband, Andrew Upton, a playwright and screenwriter, and their four children, and her native Australia, which she misses deeply. “It’s a very magnetic and alive place – you can have unruly ideas and give things a go without the sense that anyone is going to care. There is no preciousness there in relation to the arts.”

Between 2008 and 2013, Blanchett and Upton served as co-directors and CEOs of the Sydney Theatre Company, Australia’s de facto national theatre. When the board members asked them what their aims were, she says, laughing, “we told them that, at the end of the day, we want people to get in a cab and say, ‘We’re going to the Sydney Theatre Company,’ and for the cab driver to know where the fuck it is.”

What was it like running a theatre as well as acting in it? “One of the hardest things was being up there alone addressing people. It’s not like when you’re up there dancing and moving and making something with a group of people. That’s when I’m totally in my element, when it feels like I’m part of an organism.”

Recently, she has been back in Australia filming Warwick Thornton’s The New Boy, which she has co-produced and stars in. “We went to visit friends in Tasmania,” she says, when I ask her if she may eventually return home. “It had just rained and the sun came out, and suddenly there was the smell of the earth and the smell of eucalyptus. I just wept. I’m so deeply connected to that place. But we are in England and the kids go to school there and we are about to plant some trees and our cat died and once you bury a cat on the land where you live, you are connected. So, I’m torn.”

For now, she is still making sense of the transportive and deeply collaborative experience of working with Todd Field on Tár.

“It has really shaken me up in a good way,” she says. “Look, I’m always wanting to stop acting, to just step away, but this has made me think, it’s not that I want to stop, I just want to do less.” She pauses for a moment. “It’s just very hard to say no to a good idea.”

Full interview on The Observer

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?)

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?) Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)

Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)  Black Bag (2025)

Black Bag (2025)  The Seagull (2025)

The Seagull (2025) Bozo Over Roses (2025)

Bozo Over Roses (2025) Disclaimer (2024)

Disclaimer (2024)  Rumours (2024)

Rumours (2024)  Borderlands (2024)

Borderlands (2024)  The New Boy (2023)

The New Boy (2023)

Reading what she says or listening to her is always wonderful, because she is so interesting, and has had a stunning career so far.

I still keep my fingers crossed for March, and until then I wish her a very happy Valentine day.