Last Thursday, Toku Saké held a special event to celebrate Cate Blanchett’s role as their new creative director.

Cate spoke to Martha Kearney of the BBC Arts and Sunday Times about the Warwick Thornton’s THE NEW BOY, the film will be out in UK and Ireland this Friday, 15 March. More on the film’s official website here. A release date for North America is yet to be announced.

Toku Saké Event

Cate Blanchett says she’s been sake-obsessed for a long time, discovering her love for the beverage when she was working with Japanese skin care company SK-II. For more than a decade, the two-time Oscar-winning actor was an ambassador for the brand, which uses a yeast found in sake fermentation in its products.

“I went to the sake district in Kyoto, and I was exposed to the fermentation process and all of the byproducts in sake and the different ways that it can be made, and then I thought that this category is enormous,” she tells Bloomberg in London. Blanchett says she loves the ritual and intimacy of people pouring sake for one another—and drinks it chilled.

Now her newest role is creative director for Toku Sake. The rice wine is brewed in one of Japan’s coldest cities, Asahikawa, and fermented in the Hokkaido prefecture’s frosty conditions. It’s light and easy to drink, with crisp apple notes, hints of peach and melon and a subtle umami finish. The ideal serve is ice cold, and the bottles are transported in similarly chilled conditions. Toku retails for £155 ($200), which puts it firmly on the premium end of the sake market.

Blanchett says there’s a real opportunity to increase the market for sake in the West—and change people’s perceptions of the drink.

“I think that a lot of people here think they can only enjoy it in a Japanese restaurant with Japanese cuisine,” Blanchett says, but that’s not the case. She points to Toku now being served at California cuisine restaurant Sola in London and at country-chic English resort the Newt in Somerset, both of which are known for their focus on produce. “The sake market is more dynamic than people initially perceive it to be,” she says.

Blanchett’s tieup with Toku came as she was looking to create her own brand of sake. Celebrity-owned alcohol brands have taken off in recent years, with some of the most successful being George Clooney’s Casamigos tequila and Ryan Reynolds’ Aviation gin, both of which were bought by beverage giant Diageo Plc for as much as $1.6 billion. Bruno Mars has also taken a bet on rum, while Woody Harrelson announced that he’s crafting booze from artichoke leaves. “My palate had been educated through the experience of meeting master brewers,” Blanchett explains of her initial foray. “And when I tried Toku, I thought, ‘Why am I trying to create something when this liquid exists?’”

The New Boy Interviews and Film Critics Circle of Australia nominations

Warwick Thornton, ACS earned more accolades for his work on The New Boy, taking home the Spotlight Award at the 38th American Society of Cinematographers (ASC) Awards.

Cate Blanchett, a producer and star of the film, attended the awards as Thornton’s guest.

“We couldn’t be happier that Warwick’s unique cinematic gift is getting the recognition he so justly deserves with The New Boy”, says Blanchett and producer Andrew Upton. “We’re excited its universal message resonates wherever it is seen.”

This latest win follows recognition for Thornton late last year with the prestigious Golden Frog cinematography prize, awarded at the EnergaCamerimage Film Festival. “The New Boy” also won five Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTA) Awards in Feb., including a Best Cinematography win for Thornton himself.

The New Boy, which has also just collected eight nominations from Australia’s Film Critics Circle: Best Film (Cate Blanchett, Andrew Upton, Kath Shelper, Lorenzo De Maio, Coco Francini, Georgie Pym), Best Director, Screenplay, Cinematography (Thornton) Best Actor (Aswan Reid), Best Actress (Blanchett), Best Supporting Actor (Wayne Blair), Best Supporting Actress (Deborah Mailman),

Do not miss our award-winning 'The New Boy' in cinemas!

???? “Blanchett is mesmerising” — The Reviews Hub

???? — Time Out pic.twitter.com/Pxdq17ON47— Signature Entertainment ? (@SignatureEntUK) March 9, 2024

Cate Blanchett film tackles faith and colonialism in Australia

It would take a remarkable acting performance to rival Academy Award winner Cate Blanchett on screen.

But that’s exactly what untried child prodigy Aswan Reid has done in her latest movie, critics say.

Barely 11 years old when The New Boy was shot in the dusty South Australian outback in 2022, Reid’s audition was the very first tape the film’s creators looked at.

Variety calls Reid the film’s “secret weapon” while The Guardian wrote that he “delivers Australian cinema’s most impressive child performance for some time” – an assessment rubberstamped last month, when he took home the prize for Best Lead Actor at the Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts Awards.

Reid plays the film’s titular character – a nine-year-old Aboriginal orphan with mysterious supernatural powers, whose arrival at a remote monastery in the dead of night sends the place into turmoil.

The fable, which is out in UK cinemas from 15 March, is set in 1940s Australia and touches on one of the nation’s darkest chapters.

From the mid-1800s until 1970, successive generations of Indigenous children – estimated to be in the tens of thousands – were forcibly removed from their families and cut off from their culture, under policies aimed at assimilation.

The film’s backers say it “explores spirituality, culture and colonisation in a way we haven’t seen on screen before”.

Blanchett – who plays a renegade nun – has said she’s long wanted to work with Thornton and when she read the script, she was determined to have it for her production company Dirty Films.

They first began discussing the project during the pandemic, but it had been written by Thornton almost two decades earlier.

“It was so personal that he put it in his sock drawer, his proverbial sock drawer, and left it there.”

But Blanchett too was drawn to the project for personal reasons.

Her father had died when she was just 10 years old, and – despite having no religious background – she found herself seeking comfort in the rituals and community of the Catholic Church.

“I was looking for some sense of understanding of what I had perceived as the disappearance of my father – which seemed some inverse miracle. How could he be there one day and gone the next?” she says.

“I was, I think in a very simplistic way, hoping that the hand of God would come down and tell me, you know, ‘Your father’s playing golf. You’ll see him in a few years’ time.’ But of course, that didn’t happen.”

She initially had no idea about Thornton’s childhood, but they soon bonded over their similar brushes with faith as youngsters.

“His work is often quite savage and brutal, but this is a very personal story about his own experience,” Blanchett says.

“And so, we found this connection.”

Originally about a monk and an Indigenous boy, it was Blanchett’s husband and collaborator Andrew Upton who suggested putting a nun in charge of the monastery – a role usually reserved for men.

“We have a nun who’s officiating mass and we have people who were all dislocated from their metaphysical country, and so I found it absolutely intriguing to go into the exploration of what it would mean to be a nun in those particular set of circumstances,” Blanchett says.

Many of the film’s themes are very much still live issues in Australia too.

Indigenous children continue to be removed from their families at record rates by child protective services.

And when the film was released there last year, the nation was in the grips of a referendum on the constitutional recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, which was decisively rejected.

Critics of the defeated proposal argued the idea was divisive and would have created special “classes” of citizens.

But Blanchett describes it as a “missed opportunity” for the country to grapple with its complex past, and those policies that have contributed to the “eradication of Indigenous culture”.

“So many positives could have come out of it,” she says.

“I think it’s to our detriment that we have not been able to really adhere to the deep-time, vibrant history that came before white settlement.”

Oscar-winner Cate Blanchett's latest film, The New Boy, focuses on a young Indigenous Australian boy who is taken to live in a monastery.

Speaking to @MarthaKearney, Cate says Aswan Reid's acting in the role is 'magnetic', despite it being his first ever film.#R4Today

— BBC Radio 4 Today (@BBCr4today) March 7, 2024

Cate Blanchett talks grief, abandoning religion and Sunday’s awards ceremony

Never let it be said that Cate Blanchett doesn’t have range. Last year she played an abrasive conductor in Tár. Now she is starring in a film called The New Boy, playing a nun in 1940s Australia. Blanchett — who has lived in East Sussex for the past decade — enjoyed going back to where she grew up to film. “Australia’s an alive place, where the wheat actually sings,” she says. She smiles. “But I wasn’t on acid.”

The actress, aged 54, is chatty, witty, smart and graceful — picking at olives and wearing a grand pair of leather trousers. The New Boy was filmed a day’s drive from Ivanhoe, the Melbourne suburb where she spent her childhood, and its subject matter put her in a reflective mood, thinking about her father, Robert, an advertising man who died of a heart attack when she was ten. Her mother, June, a teacher, brought up Blanchett, her elder brother and younger sister.

“As a child I wanted a religion,” she says. “I wanted the strong hand of God to put a hand on my childish shoulders to say, ‘Your father is with me. He’s having fun. You’ll see him in 60 years.’” She sighs. “But that didn’t happen. And so as a ten-year-old I fled from the church and moved down to the river and spent my childhood propelled into nature. If I’d stayed inside the Methodist church I’d have a lot of bad guitar playing, but instead I rode my bike, thinking I was Nancy Drew, down by the Yarra River. I remember that as profoundly as I remember the hymns.”

Did she abandon religion because it was not giving her what she wanted? “It was not so much about what I wanted,” she says, “more what I was hoping for. Also — I was ten. But religion contains a sense of hope and also a sense of community. And, in a way, that desire for something greater than myself never left me.”

She and her husband, the screenwriter and playwright Andrew Upton, made The New Boy with their production company, Dirty Films, and it is directed by their fellow Australian Warwick Thornton, who is from the Kaytetye Aboriginal community. It’s about a nine-year-old Aboriginal boy taken to a convent as part of a policy called Breed Out the Black that aimed to bring Aboriginal children into white families and marry them off to white partners. The policy carried on until the 1970s. How much of that was that taught to Blanchett at school? “Zero. History is always taught by the victors — it still is.”

“There’s an assumption,” she continues, “that we all now respect the greater good — that if we erect a civil rights museum we’re on top of things. But things swing back in reaction. Look at the rage against the women in the workforce because men think that they’re taking their jobs. They feel confronted and can only take on so much change. Fear is under the surface. It’s …” She makes a sound to mimic the fear about to erupt.

I speak to Thornton in Australia. He and Blanchett planned The New Boy during late-night calls fuelled by red wine. “The country I come from is fed up,” he says. As for England? “You colonised us, fed us over.” Australia, he says, does not want to be taught about its past, but his film is for his fellow indigenous Australians anyway. Many cannot read due to a policy, which ran until the 1980s, that the indigenous would be educated only up to the age of nine. “But if I make a movie,” he says, smiling, “you don’t need to read …”

Blanchett helped to fund the film, to an extent. “But it was still hard,” he says. “If Cate made a film about some bloke in the sea with superpowers, then, f***, the money’s there. But this is about an indigenous issue: Cate had to fight.”

It’s easy to see how she persuaded the money people. Blanchett is very poised, much like her character in the sapphic romance Carol (2015). She’s also fun and unpredictable — as we saw when she performed on stage at Glastonbury with Sparks last year — “An all-time-high buzz.” She will be back at the festival this year. And which role is she least like? Her most watched part, that of the whispery elf Galadriel in The Lord of the Rings.

In her twenties Blanchett went to Sydney’s prestigious National Institute of Dramatic Art and started out in theatre and TV before, in 1998, playing Elizabeth I in Elizabeth, getting an Oscar nomination and securing a career that became that “something greater” she wanted. She was fretful as a teacher in Notes on a Scandal with Judi Dench and won Oscars for The Aviator, as Katharine Hepburn, and Blue Jasmine, as a bruised socialite.

“It’s funny,” she says, wryly. “If you embark on a life that touches any sort of cultural output, you’re referred to as elite, but that’s always felt like an anathema to me. A rehearsal room is a ragtag bunch of people who are curious about the lives of others and got into the arts because they’re running from something — the only thing elite about them is their skill. Actors are trying to work through something. But I don’t see acting as therapy. It’s got to mean something to other people to have any value.”

Film, though, vies for attention with TV and phones in a way that it did not when Blanchett started out. Even Tár’s box-office takings of $29 million worldwide were seen as slight — film’s role in the cultural conversation has shifted. Blanchett acknowledges this, but adds that on the stage she was used to playing in theatres with only 500 seats — so 1,000 people seeing a film is big to her.

That said, she jokes that some of her movies, such as The Good German with George Clooney, were seen by “about two and a half people … Clooney and me, speaking German? And that opening the Berlin Film Festival?” She starts giggling. “Mistake. There are films millions see, but then simply move on to the next thing. Some films are a slower burn, but you always have to risk failure — that’s the case with every project.”

The conversation turns to Oscars season and the ceremony tonight. “It’s nice to win awards,” Blanchett says, smiling with the satisfaction of someone with two Oscars, four Baftas and scores of other prizes. But she missed out on the Oscar for best actress for Tár, even though it felt like it should have been a shoo-in, especially since she had a Bafta and a Golden Globe for it.

Instead the Oscar went to Michelle Yeoh. Everything Everywhere All at Once stole Tár’s thunder and, a year on, sums up the awards perfectly. Lots of handshakes and canapés at parties only for voters to choose the wrong winner. Blanchett’s a reminder that whoever wins may not end up being the best remembered. Indeed, by the end of last year’s Oscar race Tár was being labelled as all sorts of offensive for its portrayal of cancel culture and complicated people, going through the “hot takes” mill, like Poor Things is now.

“But can I tell you?” Blanchett says, her eyes alive with mischief. “That was the most thrilling thing. You don’t want a film about which everybody is going to say, ‘Well done.’ When people debate it it’s absolutely thrilling. Tár was challenging, but travelled on the wave of the audience and not all the conversations were positive. They don’t need to be, just respectful. I don’t want happy agreement.”

The plot of Tár revolved around Blanchett’s Lydia Tár, a decorated conductor who has a troubled past and some strong opinions about identity politics. Directed by Todd Field, it was the sharpest Hollywood film in years.

“Culturally we are terrified of tough conversations,” Blanchett says. “Boss to employee. Employee to boss. Friend to friend. But we need them. We talk about radical candour, but when there’s a trigger warning in front of something you are implying that there is a lack of mutual respect or that the subject hasn’t been properly interrogated.”

She nods at a Barbican Centre coffee keep-cup she is cradling. She was in Big and Small, an experimental one-woman play, there in 2012. “One of my favourite feelings,” she says, beaming, “is when you go into the Barbican Theatre and those little doors shut. You are in there with a bunch of strangers in the dark, collectively committed to watch what you are dealt with, to then discuss robustly. It may offend you. It may challenge you. You may laugh uproariously. You just don’t know — but you are going to surrender to what is coming.”

Blanchett has been doing this for more than 30 years. I wonder how she looks back on her career — how she feels when at events they play a showreel of her hits. “I feel irked,” she says, laughing. “It’s out of context. They’re just bits. Like, ‘Here are the breasts.’ ‘Hands.’ ‘A bunion.’ If you put the whole person together it makes more sense. I find it disconcerting.”

Ageing doesn’t bother her, although, thanks to technology and Instagram filters, “nobody’s getting older — they just look like Barbie dolls … It’s not the ageing I find confronting at all,” she says. “Because that is like when you stumble across a photo of a holiday when you were 16 or one of my husband and me when we got married. It doesn’t produce regret or shame. Rather, a recognition of the joy of the experience, or a painful moment. I’m transported right back.”

Cate Blanchett and The New Boy

Cate Blanchett met the Big Issue in a South London hotel. We talked, as you do, about religious and political dogma, colonialism and white supremacy, misogyny and the perilous state of democracy.

Blanchett asked as many questions as she answered – unusual in an interview scenario – appearing as happy listening as speaking.

Turns out she’s a regular customer. She wants to know more about how the Big Issue started, how we survived lockdown, what was in the first edition, how many vendors we have, how it feels for them when people just walk on by.

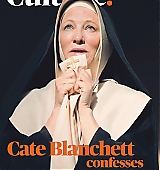

This time last year, Blanchett was at the Oscars, where Tar was nominated in six categories. Her latest venture is altogether different. In The New Boy, a film by Warwick Thornton, Blanchett plays a conflicted nun in a story of colonialism and Christianity set in 1940s rural Australia, starring opposite young actor Aswan Reid, who features alongside her on this week’s cover.

This is a film that looks beautiful and centres on a simple story. A young boy arrives at the orphanage Sister Eileen (Blanchett) runs in the absence of the priest in charge. But this is also a film with something serious to say about this country’s colonial past and the politics of today.

Blanchett said: “There’s so many failures going on with us as a species at the moment. But a big failure is a failure of imagination. To imagine that this is not about you, this is not a negative for you.

“Actually, in someone else’s opportunity is also an opportunity for you. Like when any dark family secret is tabled. It’s like a wake – there might be a painful moment, but we will move through something and then it’ll be a relief and a release.”

Available on newsstands in the UK.

Sources: Bloomberg, BCS, FCCA, BBC, Sunday Times, The Big Issue

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?)

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?) The Seagull (2025)

The Seagull (2025) Bozo Over Roses (2025)

Bozo Over Roses (2025) Black Bag (2025)

Black Bag (2025)  Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)

Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)  Disclaimer (2024)

Disclaimer (2024)  Rumours (2024)

Rumours (2024)  Borderlands (2024)

Borderlands (2024)  The New Boy (2023)

The New Boy (2023)