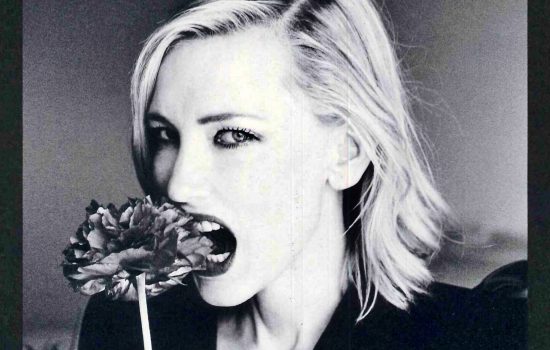

Cate Blanchett is featured on one of the covers for Document Issue No. 25 – Fall/Winter 2024-25. You can grab your copy here. She is in conversation with Alfonso Cuarón who directed DISCLAIMER*.

More interviews have been released as RUMOURS heads to its second week in cinemas in US/Canada, and DISCLAIMER* Chapters I-IV are now streaming, Chapter V releases on Apple TV+, 25 October.

Cate Blanchett: There are so many images in Roma which will be deathbed images for me, because they stay with you and interact with other things that you see in ways that you can’t form a conscious relationship to. Sometimes we don’t embrace that possibility—or the powers that be, that are going to fund the project, are frightened of that. Because they don’t think the audience will lean into it, because the algorithm shows they like this and they like that; they like this and not what you’re about.

Alfonso Cuarón: And also because they’re looking at the explicitness of everything. The way I film is not unlike how you approach performances. Your performance is so much about what you’re not seeing. You’re performing, you’re doing something, but the important thing is about what you don’t see.

Cate: What’s concealed.

Alfonso: Exactly. What is concealed.

Cate: We spend 95 percent of our time trying to conceal so much. It’s exhausting. [Laughs] And when you finally have a frank and clear conversation… Particularly at the moment—I don’t know about you, but I feel conversation is a minefield.

Alfonso: You have to tread very carefully.

Cate: I understand people are on tenterhooks. It used to be that you’re saying, ‘What are you going to do in 2026?’ And well, ‘Oh, that’s so far away.’ But people say, ‘What are you doing in six days’ time?’ And you think, I just can’t make any decisions right now. Because everything is up for grabs. And as a result, I think there’s this collective anxiety that we bring to bear to every single conversation that makes it very difficult to hear what other people are actually saying. Disclaimer is being dropped into a time when people’s ability to hear what is behind what is being said has been eroded.

Alfonso: Everything happens too quickly. Too quickly, too quickly, too quickly. So people are forced to make very quick judgments. There’s not enough time for reflection. And that transcends into conversations. Now, it’s as if you don’t state the point very clearly from the beginning, your point is lost immediately. And you can see how it happens in social media. How it’s affecting a lot of our behaviors and how the media is having an influence with this. You have a lot of people giving opinions for you. I trust that audiences can read reality. If you introduce a character who has a wealthy house and from the first scene, pretty much, they’re toasting with a very expensive wine, and then you cut to a character who lives in a more middle-class house and you see that it hasn’t been maintained for decades and everything is kind of let go, there’s really a contrast there.

Cate: A contrast in sympathy?

Alfonso: Yeah. Your audiences are going to take their stand. Just because of that class dynamic. And definitely in most of my films there’s always a dynamic that works around social class because it’s a dynamic that exists.

Cate: It’s interesting because I think that in [Disclaimer] you play not just with the power dynamics between people, but also who controls the narrative, whose perspective is driving the way we are being told the story.

Alfonso: I tend to like long takes in the films that I’ve been doing because of a couple of things: one is that as important as the foreground is the background. But also, to try to capture everything in real time. What I like is the whole dynamic which, when you create the scene, it’s about a moment that is going to happen between the actors that are completely transforming into their characters, and the dynamics that they take. Because when you are doing everything by cut, you can, with certain precision, control the outcome. Because even if an actor shows you an array of performances, then in the cutting room you can control exactly what you want. When you’re doing these kinds of scenes, you don’t have that control. Everything becomes a random moment that, if you’re comes together in a way that is a priceless moment. It is very different to craft. It almost happens randomly, because of all of the elements. And I’m not talking about the performance, but all the technical elements.

Cate: It’s that feeling of being on a roller coaster. When there’s fewer and fewer cuts, there is greater anticipatory anxiety. Once a cut is finally made, it actually means something. And, from an acting point of view—and I do think from an audience’s point of view as well—sometimes narrative makes rhythmic sense. It happens in the edit. But if it can happen on set, you’re all on the same page. It invites a slightly different way of working, which I really warm to.

Alfonso: And when you’re creating all of this, there’s these dynamics that happen. And so no take is the same.

Cate: So you have to make choices.

Alfonso: You have to make choices. And yes, it keeps you on your toes. Because you know that, whatever you do, there’s no safety net.

Cate: [In theater] your relationship to an audience is entirely different, and the presence of an audience is vitally important to the quality of the evening, whether they fully participate or participate partially. But both of those forms—theater and film—are symbiotic, I never see them as being mutually exclusive.

Alfonso: But there is something different. There is a big difference when you do a scene like the scenes that we did, that you’ll repeat, I don’t know, 12, 14 times. They are very intense scenes which you have to do pretty much in one day, maybe two days. In a very short period of time. And you have to kind of absorb the older moments that happened with a character that lead to this moment. Surely it’s very different than this moment in which you’re an actor ready to come out on stage. The theater quiets, you come out, you start performing something that you’ve been rehearsing for a month—you already have a whole background, and you’re building the moment as you go.

Cate: You’re talking about the end result of a rehearsal process—and I think the audience might think that, when actors walk on stage, what they’re seeing is the end result of something. But each performance is part of an ongoing process. When I started working in film, I stupidly thought that must be so easy because actors in film get to work and work and work until the moment is perfected. And then the director will cut all the rough bits off, and then the whole endeavor is perfect. And then of course I land on a film set and it is strangely like a theater rehearsal. From take to take, you’re building; you’re growing something. What’s different is that in a theater rehearsal room you’d put that ‘take’ aside and you wouldn’t visit that again for two weeks. And then you put the whole thing together, like a director does in a first assembly, and say, ‘This is a pile of shit, who’s gonna see this? [Laughs] It’s awful! How can I salvage this?’ The hardest thing for me in film is that it does eventually get locked off. This part, to me—when an audience will finally see something that has been filmed—it’s like opening night, but the object is final. Whereas in theater, maybe that’s where the difference is: you go out to rehearse and refine as if for the first time, in the first or second take. That’s where the nerves spring in, or the superstition. You say, ‘I know the first line, [but then] I don’t know what’s going to happen.’ You trick yourself. That’s when the theater lives. I think it dies when it’s just by rote repetition of something that you’ve rehearsed and prepared earlier. You have to find it again, with the ensemble, every night. You have to salvage it, again and again.

Alfonso: In that sense, you’re never done with it.

Cate: No, you’re never done.

Alfonso: I know actors, who when you say, ‘We’re going to do this in one take,’ they…

Cate: …they panic.

Alfonso: They panic. It’s either remembering all the lines or the positions… Also I think that—particularly actors that do mostly cinema—are used to a certain methodology, that suddenly you say, ‘Well, we’re going to do all of that.’ And it depends so much on the relationship with the other actors. Because once you’re there, the actors become your editor. They are going to give you the rhythm, they’re going to give you the dynamic.

Cate: Or not. [Laughs]

Alfonso: Or not! But what I’ve also recognized is that audiences are constantly evolving. And it happens hand in hand with how cinema, or the arts, change and evolve. I think it would be a mistake to impose on younger generations the forms of the past. Because there’s a new sensibility, there’s a new morality. It’s a different world. And with that comes new forms, the forms that they adopt, and they understand and they feel excited with. That doesn’t mean that you cannot appreciate what is in the past. But I don’t think you can impose the past on the present.

Full conversation on Document.

How Did Cate Blanchett Wind Up in the Year’s Funniest Movie?

How on Earth did you end up making a movie with Guy Maddin?

I was an enormous fan of Guy’s. I’ve been speaking to Ari Aster about one thing and another. He called one day and said, “Guy and Evan and Galen have this script,” and would I read it? I’d seen The Green Fog, which is a movie that I think every single film student should watch. So, I went, “Yeah, of course.” And I just loved the script. I love their irreverent take on things. They’re so deliberately perverse. Just when you think they might be tackling a serious subject, they run in the opposite direction. I thought it was a really great way of dealing with global anxiety and the monumental failure of leadership, through their lens.So many conceptually offbeat comedies will build up a head of comic steam and then fall apart. The concept might be very funny, but they struggle to maintain the energy or take things to another level. Rumours, I felt, didn’t let up at all. It got funnier and funnier and more existentially terrifying as it went along.

“Existentially terrifying” is probably something they should put on the poster. I mean, it’s part monster movie, part Mexican soap opera, part Douglas Sirk. And something that we constantly referred to was Buñuel’s Exterminating Angel, so it’s part fever dream in a way. I love the fact that it’s a difficult film to describe, but that’s what makes it extraordinary. People are so ready to put things into boxes. And Guy in particular, in his long and varied underground, backroom career, has remained continually curious about the way he makes films. As a result, it’s so utterly particular. You’d ask them what something meant, and it was almost like those questions are an anathema to them. There’s an internal logic to their films, but they also defy logic, so they’re silly and deep simultaneously.The masturbating bog men, for example.

It’s a good name for a punk band. The Masturbating Bog Men.It’s a metaphor that works in a variety of ways. On the one hand, they are these very physical, immediate, raw forces that almost point out the shallowness of what the G7 leaders are doing …

Yes. Or maybe the alter egos of leaders gone by.And at the same time, they’re kind of just wanking along while the politicians give speeches.

Right! Yes. Yes. Yes.I love the fact that this symbol can go in all of these directions. It opens up a variety of possibilities for the film.

I love that each of these G7s have a theme, and this one is regret. Several of the leaders are getting ready to step down, and so there’s a kind of profound melancholy and looking back over their collective relationships and the contracts that only they can understand. And the theme of regret almost leads to these bog bodies being exhumed. Do they represent unexamined colonial history, or inaction on climate change, all of these things that they haven’t exhumed before now come to consume them?The return of the repressed?

Yeah. But as soon as it starts to become a theme, the filmmakers will literally cut the film and run in the opposite direction.In your case, you have the accent and everything …

An accent of sorts. I mean, the whole thing is a kind of a parody.What’s the difference between a comedy accent and a drama accent?

I don’t know. You tell me. These things sort of evolved. I was the only one who was not playing someone from a different country, apart from Charles Dance.He’s playing the U.S. president, but he’s got a British accent, which is hilarious.

There used to be an explanation as to why he had a British accent. Somebody that the filmmakers knew in their childhood had gone away to England for a time and come back with an English accent. So, a lot of these references make personal sense to them, but they don’t feel the need to explain them or justify them to an audience. So that was cut out.In your case, though, the comic accent, you can play around with it.

I think there’s so much license in their films, because they set up a logical premise and then they set fire to it. You have to find the right place to sit, to ground it, but then also be able to explode that reality, hopefully.What does that mean when it comes to shooting the film? Is there a lot of improvisation happening, or flying by the seat of the pants?

Oh, we were definitely flying by the seat of our burning underwear! But they’re quite meticulous. I was surprised that Evan and Galen and Guy wanted a table read. We did have a couple of days round the table to nut things out, because we had to move so quickly and it was all shot at night, which I hadn’t really computed. I really did expect to be shooting this in Guy’s garage in Winnipeg, which I was quite excited by. As freewheeling as their films feel, they are quite meticulous as screenplay writers. They were quite clear about what they wanted said, and what they wanted to see.All these characters have histories, personal histories in some cases. So often, when you have to build a part, you have to create a backstory for a character. But is that something you do for a weird comedy like this?

Not really. In the same way that you probably wouldn’t for The Exterminating Angel, because it disintegrates so quickly and you become your id, or you become all of the artificial trappings that go into making a world leader. Which we see so awkwardly expressed in footage from these G7 summits. I mean, they are excruciatingly awkward, and these people are so far away from anything that resembles reality, it’s a parody in and of itself — they go through all these cultural moments and when they talk, you can see that they’ve been coached in gestural language that is powerful but non-threatening. There’s a puppetry to it. So, in the film, in a way they regress into becoming human, to becoming terrified. It was also interesting that the filmmakers were deliberately playing with cultural stereotypes, but even then they were completely unmoored. In a way, all of that stuff had to be found between the actors on set.So, how did you find them?

How did we find them? I don’t know if I did. These things are elusive. It was great. I mean, everyone always says this, but it was literally like being on an extended sleepover for six weeks. All of us spent time in this sort of little, tiny easy-up tent. There were no trailers or anything, and we just sat around in silence. Then someone would say, “Anyone want a nut bar? Can I make a coffee?” And Rolando would bring in meat and cheese —Sort of like his character in the film, the Italian prime minister. What is it like being directed by three people?

You see a lot of pairings of people making films together. In a way, it’s a bit like the old studio system where people would always work with the same producer, who had their back, who would challenge them, but also give them the limitations that they needed, because unfettered access to resources is not necessarily the most creative way to work, as Guy’s work would attest to. I didn’t realize at first that they came as a triple bill. I thought it was just Guy. But I’m so grateful that the three of them were there. And it’s a product of the three of them. When people say this is a Guy Maddin film — it’s very much made by the three of them.Initially, I thought, How is this going to work? Who do I speak to? And the way it worked out was that I would ask Guy the big, thematic questions, and he’d go, “Huh? Hmm. The answer is I don’t know.” And then two days later, he would come back, having deeply thought about the question, and he would give you the thesis on why, in a way that could be actioned. I mean, we’re not making The Mahabharata here, you know? And then Evan was really practical — really clear, quite blunt. Then Galen was sort of like this strange, technical puppet master in the background. The way they worked together was so fluid and fantastic. Because often there’s a lot of pressure on directors. It’s not the most creative way to work — because you can’t be in real time, be present, but also future-thinking, necessarily. I’d be curious to see where the three of them go together. I would work with them again in a heartbeat.

They’re like a collective brain, it seems.

They’re an amoeba.Those of us familiar with the world of international diplomacy will get some of the finer points of the comedy — all the nonsense about working papers and the protocol and stuff. But was there ever a concern that some of the humor in the film might go over the heads of those unfamiliar with, say, what the G7 even is?

I think probably it’s a more accessible film than many films that Guy has made in the past. And I don’t think you really need to understand the intricacies of the G7 in order to get the absurdity. But it helps. The film is dealing with archetypes, and with an existential human problem — the idea of talking about things rather than doing something about them — so there’s something timeless about it.But the power of the work that they’ve done together, the three of them, is that a film is not necessarily successful when it’s found in the moment. I didn’t find Guy’s films at the time they were made, necessarily. I watched My Winnipeg several years after it had come out, and then I went backwards over his oeuvre, and I realized just how influential he had been on the way people felt they could play with and subvert narrative and the texture of film. What I relished and loved about working with him is the interconnection between the theatrical experience and the cinematic experience that Guy so often plays with. So, I think that people will find it, and they might find it this year, or they might find it five, ten, 15 years hence.

Was My Winnipeg your first Guy Maddin film?

Was it? I can’t remember. I think I’d seen the film he made with Isabella Rossellini, The Saddest Music in the World. Beautiful. And “The Final Derriere,” the song that Sparks did for them, I knew. But his tastes are so eclectic. His tastes in film and music are so eclectic. He has an eclectic bunch of friends, and he loves his dog and Winnipeg as much as he loves world cinema. He’s such a strange and wonderful mix of confidence and surety and absolute, profound anxiety-ridden uncertainty. He’s able to hold both of those stakes in his films. So, there’s a febrile quality to the way he works. But he’s so open-hearted, and he cares so deeply.Is there a film that you’ve done over the years that you wish more people had appreciated?

Gosh, I can’t think of one offhand. I forget what I’ve made as soon as I’ve made it. Sometimes you can have a great time making something, but the actual product doesn’t connect with people at the time. There are certainly some films I’ve made which I’d like to forget. I do worry at the moment that there is so much stuff — and I say stuff — being made that it is so difficult to wade through it all to actually find something, and to allow the ripples of that experience to live long enough before you’re meant to consume something else. It feels like we’re living through a cinematic or televisual La Grande Bouffe. My instinct is to do less and to be quiet, and to go back onstage.So, maybe some things I’ve done onstage, I would love people to have seen. Because it’s ephemeral. A Streetcar Named Desire, that we did with Liv Ullmann. Gross und Klein, which Benedict Andrews directed, I was really proud of. And The Secret River, which we ended up taking to the National Theatre, which I was very proud of, and Uncle Vanya. Maybe those things I think about more in that way, because they are so ephemeral. But that’s the gift of theater. You have to be present and there, and it lives on in people’s memories.

[Rumours] is a comedy set in the present, at a Group of 7 summit being held in a Bavarian forest by the chancellor of Germany, a Merkel-ish figure played by Cate Blanchett. It was shot digitally, in color, and looks entirely modern. But it remains, somehow, fundamentally a Guy Maddin movie. The theme of the politicians’ summit, Blanchett’s character announces, is regret. The elderly American president is played by Charles Dance, of “Game of Thrones,” with an unexplained British accent. It is, for once, the Canadian prime minister — played by the Québécois superstar Roy Dupuis — who gets to act like a hunky, man-bunned version of Harrison Ford in “Air Force One” as the world leaders stumble upon a giant brain in the woods and find themselves menaced by masturbating zombie bog creatures. “There’s a new influence there,” Aster says, “which I think is Evan and Galen. It feels like sort of an evolution of what Guy was doing on his own, in both aesthetic terms and, I don’t want to say ambition, but there’s a new kind of strangeness.”

Blanchett described the result to me as “a wider doorway for an audience unaware of their work to step through. In that way it feels like a departure.” The movie received strong reviews after premiering at the Cannes Film Festival, where Maddin had never had a feature screened before, and this fall it will receive the biggest theatrical release of Maddin’s career. Evan Johnson described a call with Bleecker Street, the U.S. distributor, in which the topic of screen numbers came up. “Someone said, ‘It’ll be something like five,’” he said. “And before he finished, we were like, ‘Five! Oh, that’s pretty good. That’s more than I expected, to be honest!’ And then he said ‘hundred,’ and we were like, ‘What?’”

“Only 499 more theaters than I had before,” Maddin said.

“Rumours” is very much like my experience of Winnipeg: an exercise in the uncanny. Going into the screening, I wasn’t sure how a Maddin film stripped of Maddin’s early-cinema artifice would work. But “Rumours” locates its own zone of artifice in the bright digital present. Like previous Maddin films, it takes melodrama and hyperbolizes it into comedy — only here the melodrama is rooted not in old films but in soap operas and Lifetime movies. As the self-important G7 leaders gather to draft a vague and meaningless “provisional statement” about an unspecified global crisis, there are mawkish musical cues, smoldering glances and secret assignations. The Canadian prime minister broods over a stupefyingly mundane financial scandal back home, prompting the British prime minister, played by Nikki Amuka-Bird, to murmur, “He feels the burden of leadership.” The mansplaining French president mentions that he’s writing a book about the “psychogeography of graveyards.” The political satire and endlessly quotable dialogue might bring to mind Armando Iannucci (“Veep,” “The Death of Stalin”), but “Rumours” is both sillier and more surreal than that, building to a delirious, apocalyptic climax. “The film is a fever dream, in a way,” Blanchett told me. “Therefore, it could hold all of these tonal shifts. At times it’s lit like a really bad political television interview. At times it’s lit like Douglas Sirk.”

They shot the film in Hungary. “When I got the call,” Blanchett said, “I was so excited: ‘I’m finally going to Winnipeg!’ I was so disappointed when they said, ‘No, Budapest.’” It was the directors’ first time working with a cast of entirely professional actors of such stature. “They memorized their lines,” Galen said, “which, for some reason, I was so surprised by that.” The directors had no delineated roles, but Evan took the lead on directing the actors while Galen focused on technical matters and Maddin took on “the big existential thematic questions,” Blanchett said. She was accustomed to working in theater, she said, so this level of collaboration felt natural enough. “It did concern me at one point that they were all sharing the same apartment,” she added.

He had rarely shot on location in the past, preferring the total control of the studio. “I don’t like literal-minded things that much,” he said. “I don’t like worrying about continuity.” Patiently scheduling a limited number of setups per day also ran counter to what Galen called the “artful sloppiness” of the classic Maddin style. “It’s hard to even call what I used to do a setup, because I just wander around with one of the cameras,” Maddin said. “Guy kind of likes the performative aspects of directing,” Galen said. Maddin agreed, acknowledging that the slow pace of a normal movie shoot felt tedious to him, and that he had the most fun directing certain scenes “the way I used to direct my silent movies, where the camera is rolling and I’m actually just shouting to Cate Blanchett what she’s seeing: You’re seeing a bog mummy. You’re not sure what it is. You see it. It’s touching itself! Why is it touching itself? You’re confused! Now you’re horrified! Now you’re disgusted! That sort of thing.” Blanchett described that day’s shoot as “literally an inner monologue Guy was giving voice to for the first time. I learned a lot about his childhood, some of it not to be repeated.”

“Rumours” felt like a necessary change for Maddin. So far, everyone else seems pleased by it, too. “I think they were surprised that we were able to make a normal movie,” Galen said of the distributors. “And they’re overjoyed about that. A normal movie with Cate Blanchett in it.”

Full interview on NYT

Starring in the new Bleecker Street film Rumours, playing German Chancellor Hilda Orlmann alongside other fictitious world leaders during a rather bizarre G7 Summit, when I asked Cate Blanchett, 55, what it was about this film’s character and story that made her want to take this on next, the two-time Oscar winner quickly cut me off by joking, “That made us want to end our careers? I thought I’d go out with a bang!”

When I followed up that Rumours from filmmaker Guy Maddin is an apocalyptic tale, so that is perfect, Blanchett said, “Don’t you feel every second Wednesday feels like the end of days? There are so many conflicts around the world – what we’re doing with the climate. There’s an expression in Australia – I have had it up to pussy’s bow. I feel like we’ve all had it up to pussy’s bow with the failure of leadership. We feel so powerless, so it’s a great thing to be able to go into a cinema with a bunch of people and laugh at the absurdity of the situation that we’re in.”

In reality, Blanchett remains a Goodwill Ambassador with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). So, with elections happening all over the world right now, including within the U.S. in November, I brought up with Blanchett that even though Rumours is a comedy-horror satire, it can be perceived as a timely story that can be a wake up call for our society. Being one of the stars and an executive producer on this film, I wondered if Blanchett saw that, as well.

“Definitely! I mean, I think that’s totally the baggage that the audience will bring into the cinema with them. If you’ve looked at the outcomes of the G7, when the stakes are so high – they’ve never been higher – but yet, it’s like they’re speaking a foreign language that the average citizen can’t even unpick. It feels we’re so lost, in a way – and so, if anything will urge people to go out and vote, maybe it’s this movie. I don’t know! Look, you could call it a political satire but it’s also like an episode of Scooby-Doo. It’s so deliberately stupid. A stupid film for stupid times.”

This year also marks the 25th anniversary of one of Blanchett’s early acting roles, playing Meredith Logue in the 1999 film, The Talented Mr. Ripley.

After reminding Blanchett of the film’s anniversary, which also starred young Hollywood newcomers at the time – Matt Damon, Gwyneth Paltrow and Jude Law – she said, “Films like that don’t get made anymore. The types of film the late, great Anthony Minghella made – they don’t get made like that anymore in those ways. It was so beautiful. It was made at the time of another time. There was a kind of sense of intelligent nostalgia in there. I am quite nostalgic for those experiences and I met such great actors – the late, great Philip Seymour Hoffman. We hung out for three months in Italy together and we got to know each other, and it’s a beautiful film. There was a Ripley made with Andrew Scott, who I worship as an actor. It was great but it was so different.”

As I concluded my conversation with Blanchett, I asked if she has noticed her creative mindset evolving towards her interests in the projects and stories that she chooses to take on within her career today.

Blanchett said, “It’s very hard. I find it in the moment, with the world in such a state of flux, to know where to apportion one’s time because the biggest luxury is time, right? I have four children and I have a garden, and I feel in a way, I’m more productive in my garden than I am anywhere else. Sometimes, it’s those small things that are really important. This film is a small, low budget endeavor but it somehow feels really big and it was super important to me, and felt like the only way to tackle all of these issues that are swirling and things that I’m concerned about in my head. It felt like the right way to kind of approach it because it’s so ridiculous and overwhelming. It feels like in timing, in a way, one’s career is built out of.”

Full interview on Forbes

Asking for a friend, of course. ? Like sands through the hourglass, so are the days of global summits and personal agendas! RUMOURS starring Cate Blanchett is now playing only in theaters. #RumoursMoviehttps://t.co/IYl2oGpIfy pic.twitter.com/KLtuOa6REq

— Bleecker Street (@bleeckerstfilms) October 21, 2024

Being a Goodwill Ambassador for @Refugees, I spoke with Cate Blanchett about how her new #RumoursMovie can perhaps be a wake up call for voters of their world leaders right now. @bleeckerstfilms @Elevation_Pics

Get MORE from #CateBlanchett at @Forbes: https://t.co/ztLOUv5V39 pic.twitter.com/BXGDIEANaw

— Jeff Conway (@jeffconway) October 18, 2024

Do YOU know the celebrity you share a birthday with?

I do and it’s #CateBlanchett on May 14th!

So, you better believe that when I had the chance to interview her, I took a moment to share our Taurus connection and celebrate our birthday together! ? https://t.co/ztLOUv5V39 pic.twitter.com/Z2W4B9Slk3

— Jeff Conway (@jeffconway) October 17, 2024

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?)

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?) Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)

Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)  Black Bag (2025)

Black Bag (2025)  The Seagull (2025)

The Seagull (2025) Bozo Over Roses (2025)

Bozo Over Roses (2025) Disclaimer (2024)

Disclaimer (2024)  Rumours (2024)

Rumours (2024)  Borderlands (2024)

Borderlands (2024)  The New Boy (2023)

The New Boy (2023)