Alfonso Cuarón’s DISCLAIMER* has been nominated in four categories at the 30th Annual Critics Choice Awards. Guy Maddin, Evan Johnson, and Galen Johnson’s RUMOURS is in cinemas now in Australia, UK, and Ireland. New podcast and video interviews with Cate Blanchett, Nikki Amuka-Bird and Guy Maddin below.

Guillermo del Toro is remastering the black and white version of NIGHTMARE ALLEY with extended cut.

I am remastering the B&W Nightmare Alley w an extended cut. Stay tuned

— Guillermo del Toro (@realgdt.bsky.social) December 3, 2024 at 11:08 AM

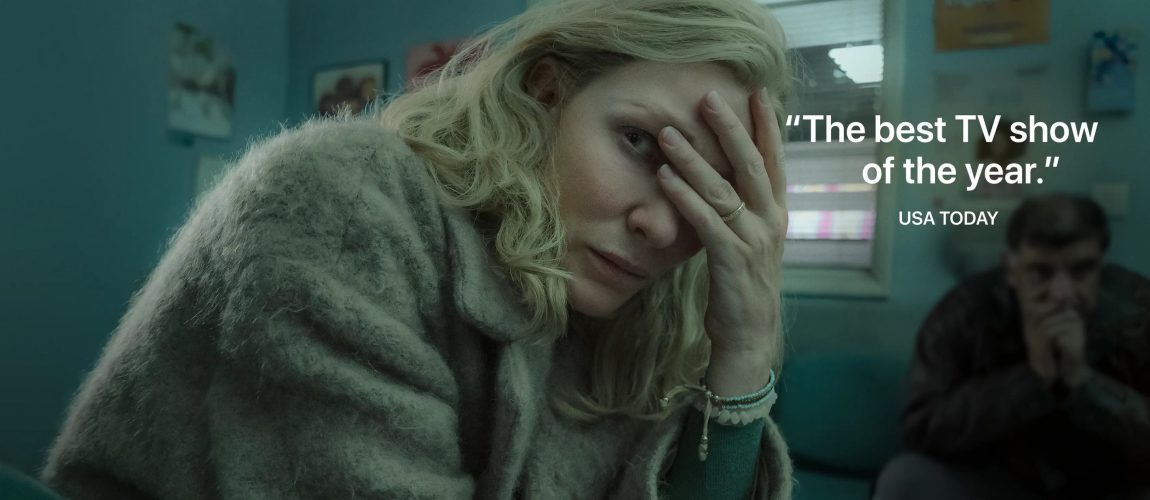

Disclaimer* CCA Nominations

Disclaimer* earned nominations in these four categories: Best Limited Series, Cate Blanchett for Best Actress in a Limited Series or TV Movie, Kevin Kline for Best Actor in a Limited Series or TV Movie, and Leila George for Best Supporting Actress in a Limited Series or TV Movie.

The Critics Choice Association (CCA) announced today the TV category nominees for the 30th annual Critics Choice Awards. The winners will be revealed at the star-studded Critics Choice Awards gala hosted by Chelsea Handler, which will broadcast LIVE on E! on Sunday, January 12, 2025 (7:00 – 10:00pm ET / PT) from the Barker Hangar in Santa Monica. The show will also be available to stream the next day on Peacock.

BEST LIMITED SERIES

Baby Reindeer (Netflix)

Disclaimer (Apple TV+)

Masters of the Air (Apple TV+)

Mr Bates vs the Post Office (PBS)

The Penguin (HBO | Max)

Ripley (Netflix)

True Detective: Night Country (HBO | Max)

We Were the Lucky Ones (Hulu)BEST ACTRESS IN A LIMITED SERIES OR MOVIE MADE FOR TELEVISION

Cate Blanchett – Disclaimer (Apple TV+)

Jodie Foster – True Detective: Night Country (HBO | Max)

Jessica Lange – The Great Lillian Hall (HBO | Max)

Cristin Milioti – The Penguin (HBO | Max)

Phoebe-Rae Taylor – Out of My Mind (Disney+)

Naomi Watts – FEUD: Capote vs. The Swans (FX)BEST ACTOR IN A LIMITED SERIES OR MOVIE MADE FOR TELEVISION

Colin Farrell – The Penguin (HBO | Max)

Richard Gadd – Baby Reindeer (Netflix)

Tom Hollander – FEUD: Capote vs. The Swans (FX)

Kevin Kline – Disclaimer (Apple TV+)

Ewan McGregor – A Gentleman in Moscow (Paramount+)

Andrew Scott – Ripley (Netflix)BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS IN A LIMITED SERIES OR MOVIE MADE FOR TELEVISION

Dakota Fanning – Ripley (Netflix)

Leila George – Disclaimer (Apple TV+)

Betty Gilpin – Three Women (Starz)

Jessica Gunning – Baby Reindeer (Netflix)

Deirdre O’Connell – The Penguin (HBO | Max)

Kali Reis – True Detective: Night Country (HBO | Max)

Rumours Interviews

What was it like shooting for 23 nights in the woods?

Cate Blanchett: Honestly, when Guy approached me about this, I thought we’d be shooting in Winnipeg and I’d be in his lounge room, or in some sort of mocked-up soundstage. And all of a sudden, we were in a forest in Budapest doing five weeks of nights. It wasn’t what I expected. I’d never done that many night shoots back to back. But there’s something kind of magical about it because you are on a time that only we understand. You wake up at 2 in the afternoon.

Nikki Amuka-Bird: We definitely understand what it’s like to overcome your fatigue, and the characters are kind of delirious. We were getting more and more delirious as it goes on. It was very useful in that way.

It’s apocalyptic – do you think that’s the movie we need right now when we’re talking world politics?

Denis Ménochet: Not really. There’s a lot of good things in the world still. There are good people I know, and good things. I don’t want to think like that because otherwise you don’t enjoy yourself. No?

Nikki Amuka-Bird: I’m embarrassed to say that I’m an eternal optimist. Yeah, there’s a lot to be afraid of at the moment. It seems like an omni-crisis. But I do have this kind of faith in humanity at the end of the day to somehow turn itself around. I think that’s what we’re looking at in the movie. What if you’re only left with that fear and confusion? How does that evolve, and where does that end up?

Cate Blanchett: Yeah, and what happens when all of the signifiers of your life, and your position, and your relationships drop away? And then suddenly you’re in a gazebo, and you don’t know how long you’ve been there. It’s a bit like A Midsummer Night’s Dream. They’ve suddenly all gone. It just suddenly changes, and you’re in this altered state. Look, I think somehow, now, the setting and the atmosphere and the tone and the image that they finally look out on seems much more possible than it did 15 years ago. It’s important to look at those things head on. But sometimes if you talk about them in a head-on way, you lose an audience. How do you use the collective anxiety and despair that any thinking person – apart from Denis – is feeling? But also invite an audience to laugh at it, and feel like they could go out slightly refreshed and more purposeful? And if it makes them talk about those things, I think it’s fantastic. It did feel more and more like a documentary.

Are you an eternal optimist like Nikki is?

Cate Blanchett: I think I’m probably an optimistic pessimist. You know, plan for the worst, hope for the best. I don’t like making fun of the state of the world. I love the world. I don’t think what we’re doing to the planet is at all amusing. I don’t think systemic, fiscal inequality is at all amusing. But you can satirise it, and invite people to see it and talk about it. That’s what I love about cinema. It asks you to engage in the world of someone else’s invention, and to imagine a way into different storylines. It’s expansive as an audience member, and I certainly find that as an actor.

Charles Dance: I despair with politics, really. The worst thing that happened, of course, was that [Britain] decided to leave the European Union. It was one of the most depressing days in the history of my country. But I didn’t look at this script politically, actually, at all. For me I thought this was a cross between Luis Buñuel and an episode of Monty Python’s Flying Circus. And I’m a fan of both of those things. It’s why I wanted to do it.

Rolando Ravello: For me, I think that an actor or a director or a screenwriter has the possibility to come up with a way of thinking for people. For me, it’s an occasion to speak with other people – only speak without judgement. To only speak to reflect. This is important for me.

Cate Blanchett: I feel like this is as much a comedy or a satire or a tragedy as it is an episode of Scooby Doo. I’ve never seen the current state of affairs played out with that particular tone. It’s a zombie movie and it’s a Mexican soap opera. And that’s what I was so interested and curious to see what an audience would make of it, because we were discovering the tone as we made it. Guy [Maddin] has always had a unique perspective that’s really playful and wicked and naughty, but also soulful and yearning and so full of self-reflection. It’s almost like a parallel reality that is able to speak, in a way, more truthfully to the environment that we sit in because he’s been so outside of mainstream cinema. If you haven’t seen The Green Fog, I highly recommend it. It’s astonishing.

Roy Dupuis: I had worked with Guy before, and he gave me the two most extraordinary shooting days of my career. It was like being a kid, and doing some sketches in my basement. This shoot was completely different. It was a big production, and very well-written. But there’s one aspect of the movie that kind of gets my interest. It’s the fact the world is changing very quickly, because of – mostly – AI. We hear a lot about it. I’ve been aware of that for the last 10 years, and that’s one aspect that I found interesting.

Does AI worry you?

Cate Blanchett: I don’t think we’re going to ever replicate the truly human, because we’re mortal, and that’s what gives us all our activators and all of our understanding and struggle with the world in which we live. That’s why all those middle-aged billionaires are trying to go to Mars, because they’re not confronting the fact that they too shall die, and AI doesn’t have that knowledge. It could replicate a synthetic understanding of that, but it doesn’t have it. I think it’s a huge threat. I was really grateful to the actors’ strike for many reasons, but for bringing that AI conversation into the mainstream. This touches on it, but it’s not a film about AI. But people might step out of the cinema talking about it.

Charles Dance: There were so many extraordinary advances in the last hundred years, far more than there’s been in the last thousand years. Suddenly, we as a species, we’ve yet to learn the law of cause and effect. We think, ‘Yes, we can do this. We can do this. We can do this’. Every now and again, somebody says, ‘Yeah, but what if we do?’ You know? I think that question that needs to be asked very, very loudly with AI, because it’s incredibly powerful.

Roy Dupuis: I personally think it’s going replace a lot of jobs, but making movies with real people is going to become precious, also. But I think it will happen. It’s really hard to stop.

Charles Dance: Years ago, I voiced a character in a cartoon. There was a comic in England called the Eagle, and one of the strips in it was a space thing. I went in to voice one of these characters. As I was going in, Albert Finney – bless him – was coming out. He saw me, and he said, ‘The writing’s on the wall, kid’.

How did you find your characters, did you base them on anyone?

Cate Blanchett: There’s so few examples of female leadership but there’s certain signifiers for what represents a powerful woman in politics. There’s an iconography to it, and the gestures, and the way the men use it, and the way women have to use those male gestures. You can just see them being coached. They’re so separated from themselves, and the more they live a public life and speak in public, their voice changes. So there was a construct and an artificiality to them as human beings, in a way that I felt that the further they went along, the more human they became. I think we as citizens of our various countries are culpable for creating leaders as part of our societal ID.

Charles Dance: We purposely didn’t push it in any direction. I guess if somebody sees a parallel in that with me and Joe Biden, then fine. OK. But that wasn’t in my head at the time.

Roy Dupuis: I looked at the archive videos that Guy and Galen and Evan sent us, just to see the body language.

What laws would you pass if you took on the role for real?

Cate Blanchett: No pineapple. There’d be no pineapple in Germany. I would outlaw pineapple. I don’t know!

What do you think world leaders will think if they see the film?

Cate Blanchett: I think any leader worth their weight in salt has a sense of humour about themselves. When you lose your sense of humour about yourself and your position…

Did playing these roles make you think about the corruption of power?

Denis Ménochet: It’s very isolating to have too much power, because then you change, and then you have no discernment, and everyone will say yes to you. I think it’s a lonely thing to have power. That’s how I feel.

Cate Blanchett: I think with power, we build people up. We build people up to tear them down. We’ve done that for millennia. I think it’s not only that you might change, but people might change in the way they deal with you.

How do you deal with being built up?

Cate Blanchett: My very first time in Cannes, I was in a very small Australian film in the marketplace, and I literally had bruises on my ribs from being elbowed out of the way to get to whatever movie star was there. And then I was back two years later with a film, being walked down with basically gladiatorial horses, and watching these other people being elbowed. It was so surreal.

Does that experience keep you humble?

Cate Blanchett: It tells you how the whole thing is a hall of mirrors. It’s so weird. We are really a weird species. And I think that’s what Guy and Evan and Galen are leaning to – it’s the human insanity.

Full interview on Hollywood Authentic

That’s why you cast me, wasn’t it?” says Cate Blanchett, addressing the Canadian filmmaker Guy Maddin. He’d just relayed his mission statement: “I want my work to be both beautiful and stupid at the same time.”

Maddin is the quiet king of dreamlike fantasias that make David Lynch look sedate. In films such as My Winnipeg, The Forbidden Room and The Saddest Music in the World, he’s made a mockumentary about himself, riffed languorously on the memories of a moustache, and given Isabella Rossellini prosthetic legs filled with beer.

Blanchett, meanwhile, is a two-time Oscar winner and mercurial superstar, as comfortable in arthouse drama such as Tár as she is in a blockbuster like Ocean’s 8. She’s also, every once in a while, slightly mad. There she is performing with Sparks at Glastonbury. There she is playing 13 different women for a 130-minute art installation for German surrealist Julian Rosefeldt. There she is with a bright red fright wig in Borderlands, quite possibly the worst film of 2024. Blanchett, it goes without saying, likes a bold swing. So it’s somewhat inevitable that she and Maddin would eventually cross paths.

Blanchett loves a bit of silliness. “Anything really perverse and playful can be deemed as being a bit stupid,” she says. “But it’s important to be in that space. You need to approach every film script or theatre text as if you know nothing. You have to muck around with them. You can’t be too reverential. Because stupidity is incredible. Even when you’re dealing with the G7.”

We’re meeting over Zoom to talk about Rumours, an apocalyptic political comedy (with masturbating zombies, obviously) about world leaders who find themselves lost in a dark German forest. While the trees burn to the ground around them, they speak loudly about very little and seem to walk forever in circles. There may be a metaphor in there. Blanchett is the German chancellor, an elegant fool with a history in racist theatre productions. Charles Dance, as the president of the United States, keeps falling asleep. Alicia Vikander, as a representative of the European Union, is obsessed with an enormous glowing brain she’s found in the woods.

“It looked like you could get a teaspoon and have a little bite of it, didn’t it?” Blanchett asks me, with dramatic élan. “But, honestly, I think it was probably toxic.”

“It was made out of latex, then filled with something like a thousand monkey brains so it’d have the right weight,” Maddin explains, stone-faced and lying (hopefully).

Blanchett winces. “You’ll need to put a trigger warning for vegans on this article, Adam.”

Maddin shakes his head. “No, no, Cate, these monkeys had died of old age. It’s fine. They’d donated their brains.”

Blanchett nods emphatically. “But I can’t talk about that – I signed an NDA.”

Blanchett, 55, is in a sunny hotel room in London, dressed in a blood-red power suit, her hair cut into a sharp blonde bob. Maddin, 68, is in the dark shadows of his home office in Winnipeg, Canada. The pair share a fun, circular rapport: Maddin provides the deadpan set-up, Blanchett the gentle, self-mocking retort.

When it came to Rumours, Maddin and his regular collaborators, brothers Galen and Evan Johnson, had spotted an inherent ridiculousness to the G7, that annual get-together of global power players determined to get things done and set agendas. They’d watch hours of footage of leaders shaking hands and standing awkwardly in lines. “It’s a bit like the Christmas fireplace channel,” he jokes, of that baffling 24-hour broadcast found at the far reaches of cable television that shows nothing but a roaring fire. “And it’s so exciting to watch them – these strange rituals, and strange bits of geopolitical choreography. And they talk as if they’re in some kind of Iron Age trance.”

Blanchett was already a fan of Maddin’s, and got her hands on the Rumours script via its producer Ari Aster, the eccentric genius behind Midsommar and Beau Is Afraid. She adored it. “It deliberately avoids being pigeonholed as a political satire or a B-grade thriller or a monster movie,” she says. “Just when you think you know what Rumours is, it turns another corner.”

In her role as an ambassador for the UN Refugee Agency, Blanchett has orbited the real political world for a while, and she tells me she has a degree of empathy for the politicians she’s met. “They’re human beings labouring under systems that don’t serve them or anybody else,” she says. “The big elephant in the room is overpopulation, really, and climate change, and it’s really difficult for any single person or any single country to approach these things. You’re constantly trying to make the family Christmas work while knowing it’s going south.”

On this subject, though, Maddin insists that Rumours is apolitical. You can vaguely see Joe Biden in Dance’s US president, and there’s a touch of Angela Merkel to Blanchett’s character, but never enough that it feels like overt pastiche. “We made sure the politicians’ ideologies were neutered,” he says. “They really could have been a bunch of plumbers, or high school alum getting together in a forest.”

I’m not entirely convinced of that, but part of the thrill of Rumours, Blanchett says, is the debate it inspires. “What I love about this film – and maybe this is inherently political – is that it avoids answering the question of ‘what is this film actually about?’ I love that perversity in cinema. I’m not so keen on it in politics.”

Does she ever get nervous about talking about politics as a public figure? She wrinkles her nose. “I think you have to have a healthy lack of consequence as an actor,” she says. “It’s a big difference if you seek to go about and offend people. But I think it’s great to gently nudge people or provoke a conversation.”

She understands, though, why some actors might be reluctant to add their voices to political discourse. “You get asked those questions and suddenly an off-the-cuff comment gets repeated in Portuguese and then in Mandarin, and back into French, and then vaguely into English,” she says. “Then a journalist says, ‘but you said this’, and I can’t remember it and it’s put up there as a headline next to something that is genuinely important.”

In what is ever so possibly a total coincidence, we happen to be speaking a few days after she apologised for calling herself “middle class” in an interview.

“So I don’t think actors are frightened,” she continues, “they just don’t want to get in the way. Your job is to do what you do, and sometimes the best response is to go out there and be a good person and try to make good work.”

How long that will go on for Blanchett, though, has been the subject of some debate. She has been open in recent years to pondering if not retirement then at least a slow retreat from public life. In one interview, during the promotion of her prickly 2022 epic Tár – which netted her an eighth Oscar nomination – she suggested she might even pack it all in to make cheese.

“Oh, that’s such a good idea!” she says when I remind her. “See I have all these good ideas but I never realise any of them. I just keep acting – I’m terribly sorry.”

In all seriousness, though, she does think about it. “I think my natural state is to dig a little hole underground and burrow in for the winter,” she says. “It takes a lot to get me to come out of it and work. But then you get seduced by great artists who are doing interesting things, and it’s a way of staying connected. Even though my natural instinct is to be quiet – she says, while sitting here talking to The Independent.” She breaks into a laugh. “So there’s a disingenuous quality to all of this, too.”

Rumours tussles with some of the bigger questions, too: what will the end look like? Does any of this matter in the long run? What are we doing here? I’m curious if Blanchett and Maddin ever think about total annihilation.

“Oof,” Blanchett says. “I just lost some bladder control.”

“I hate to think about it,” Maddin says. “But I don’t think the message of the film is that the world is going to end. That’s just a narrative trajectory. You’ve got to take it to the end of the world for it to be a proper bedtime story.”

Blanchett slightly disagrees.

“But, Guy, the film does tap into the things that keep people awake at night,” she says. “It just does it in a way that sort of holds your hand through the darkness. So, yes, it’s a bedtime story, but it also giggles with you under the duvet.”

What they can agree on, at least, is that Rumours – named, abstractly, after the classic Fleetwood Mac album that was created amid chaos, tension and love affairs – is completely, majestically inexplicable.

“We’ve made a genre all to ourselves,” Maddin says. “Which, of course, makes it impossible for our distributors to market the film.”

“It helped, though, that you cut out the big, Esther Williams swimming pool musical number,” Blanchett shoots back. “That probably made it easier.”

[Rumours] explores events after a calamity at a G7 summit leaves an eccentric array of world leaders fending for themselves, and at various points includes such bizarre sights as a tribe of reanimated “bog bodies”, an inexplicably large human brain, and Charles Dance playing an American President with an upper class English accent.But despite all that, star Cate Blanchett – who plays fictional German chancellor Hilda Ortmann – says there is something very truthful about its portrayal of a world in crisis, as she explains in an exclusive interview with RadioTimes.com.

“The way I think that they’ve thrown it at the audiences, is they don’t try and make sense of it,” she says of the directors’ approach.

“But it is very funny, and I think the world has become even more absurd since we made it. And so there’s a terrifying, documentary-esque quality to it that I didn’t really see coming!”

Nikki Amuka-Bird plays the film’s UK Prime Minister Cardosa Dewindt, and after witnessing audience reactions to the film so far, can only agree with her co-star’s assessment.

“Some people have said, you know, it’s, too close to reality for them,” she says. “Which is worrying and surprising!”

The assorted Presidents, Prime Ministers and Chancellors in the film are not based on any specific world leaders, but Blanchett and Amuka-Bird both found themselves studying real B-roll footage from G7 summits to get a better handle on their characters’ interactions. And although those characters are often displayed as clueless, bumbling idiots, this research process gave the actors a greater degree of understanding for them than they might have initially expected.

“That was a revelation to me,” Blanchett says of watching the footage. “I mean, how deeply awkward these situations that they were placed in. They were all photo opportunities. There were no private moments. And how unmoored from their physical selves they seemed to be, I found fascinating and compelling. So it made me have a great deal of empathy for them.”

“The performance we require from them as well,” adds Amuka-Bird. “We need them to be neat and tidy, married and morally correct, and great cooks, or whatever it is that we need them to be. And you could feel, as you say, that awkwardness, and that’s a great starting point. They’re the only people who know what its like to lead a nation, and that’s an isolating thing. And so they have that in common.

“And slowly, during the course of their journey, they kind of form these bonds, these strange bromances, there are affairs and all sorts of unexpected relationships formed between them. But I think, you know, we played it straight. That’s a cliche, but it’s like, we don’t need to impose an idea for other people to have an opinion for themselves.”

As the film becomes increasingly detached from reality, there’s a chance some viewers might become rather lost in the woods trying to make sense of everything, just as the politicians themselves do in the film.

But Blanchett says that rather than looking for explicit, easy answers that explain away everything going on – just what is the meaning of that giant brain, for example – it’s better to embrace than sense of the inexplicable and get caught up in the madness.

“I connected with Guy over a love of Buñuel, and one of both of our favourite films is The Exterminating Angel,” she says, referencing the 1962 masterwork by the famed Spanish surrealist.

“And he said, ‘Oh, actually, that is quite an interesting reference point for this film,’ in that, if you view it like a dream, dreams make absolute sense in the moment, but often from two conflicting, contradictory sort of stimuli.

“And so I think, like a lot of Guys’s work – and I think it’s a hallmark of great creativity – is when you can allow these conflicting, often antithetical states to coexist and allow the audience to make sense or not. And so that was the place that I worked from, because I really didn’t try and pin it down to any logic.”

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?)

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?) Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)

Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)  Black Bag (2025)

Black Bag (2025)  The Seagull (2025)

The Seagull (2025) Bozo Over Roses (2025)

Bozo Over Roses (2025) Disclaimer (2024)

Disclaimer (2024)  Rumours (2024)

Rumours (2024)  Borderlands (2024)

Borderlands (2024)  The New Boy (2023)

The New Boy (2023)