UNHCR Goodwill Ambassador Cate Blanchett and International Film Festival Rotterdam’s Hubert Bals Fund launch Displacement Film Fund, a new short film grant scheme supporting displaced filmmakers or filmmakers with a proven track record in creating authentic storytelling on the experiences of displaced people. On 1 February, Cate will be in conversation with other filmmakers on how the film industry can better represent the voices and experiences of the displaced.

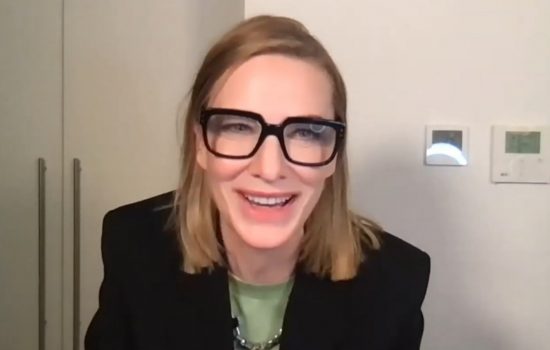

Last November, when Cate presided the main competition jury at Camerimage Film Festival, Elle Polska sat down with her for an interview which is now published on the February 2025 issue of the magazine.

Cate Blanchett and IFFR’s Hubert Bals Fund launch the Displacement Film Fund at IFFR 2025

UNHCR Goodwill Ambassador Cate Blanchett announces new pilot scheme with support from Master Mind, Uniqlo, Droom en Daad, the Tamer Family Foundation and Amahoro Coalition as Founding Partners, the HBF as Management Partner and UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, as Strategic Partner.

Cate Blanchett, actor, producer and global Goodwill Ambassador for UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, together with IFFR’s Hubert Bals Fund (HBF) today announced a new short film grant scheme which will benefit 5 filmmakers in its pilot version. Bestowing up to five individual production grants of €100,000 – the Displacement Film Fund is established to champion and fund the work of displaced filmmakers, or filmmakers with a proven track record in creating authentic storytelling on the experiences of displaced people.

The Fund – which is backed by a coalition of leading film industry experts, creators, business leaders and philanthropists – will be formally launched at IFFR’s 54th edition where Blanchett will appear on an IFFR Pro Dialogue panel on Saturday 1 February, 15.00 with Koji Yanai, Waad Al-Kateab, Jonas Rasmussen and Head of HBF, Tamara Tatishvili, moderated by Uzma Hasan – to discuss the scheme’s origins, aims and the urgency of its focus. The purpose of the Fund strongly aligns with the HBF’s history of supporting underrepresented voices, especially with filmmakers from countries where local filming and infrastructure is lacking or restrictive. The shared ambition is that the pilot project develops into a longer-term legacy.

With one in every 67 people on earth forcibly displaced due to conflict, war, or persecution, the global community is witnessing an unprecedented crisis. The Displacement Film Fund was first initiated at UNHCR’s Global Refugee Forum, the world’s largest gathering dedicated to addressing challenges faced by refugees and their host communities. Cate Blanchett joined fellow UNHCR supporters Ke Huy Quan, Echo Quan, Ayman Tamer, Koji Yanai, and Isaac Kwaku Fokuo to develop the idea at the event. In order to deepen the insights, expertise and reach of the Fund, Blanchett sought out and recruited a wider group of film industry experts and creatives, all of whom have a personal connection and/or strong interest in the issue of forced displacement.

The Selection Committee will be chaired by Cate Blanchett and includes journalist and documentarian Waad Al Kateab (We Dare to Dream, For Sama), actor, producer and musician Cynthia Erivo (Wicked, Drift), director and screenwriter Agnieszka Holland (Green Border), IFFR Festival Director Vanja Kaludjercic, educator, activist and refugee Aisha Khurram, filmmaker Jonas Poher Rasmussen (Flee), and Amin Nawabi [alias], an LGBTQ+ asylum seeker who is Jonas’ inspiration for the story of Flee.

Filmmakers will be selected for the pilot Fund following a two-step process. A longlist of filmmakers will be determined by the Nominations Committee and then the Selection Committee will decide on final recipients with selected filmmakers announced during Cannes Film Festival 2025. The finished projects will have their world premieres at IFFR 2026.

Cate Blanchett, UNHCR Goodwill Ambassador, said: “Film can drop you into the texture and realities of someone’s life like no other art form. Working with UNHCR I have engaged in both the large-scale impact and the vast statistics of forced displacement as an issue faced by millions of people – but I have also been fortunate to meet affected people directly and engage with their stories and experiences. It is this aim of creating personal, intimate touchpoints that the Displacement Film Fund is driven by. When people are forced to leave their homes, they lose access to the most basic support, but as artists they also lose access to the means to make work at a time when it is more vital than ever. I’m grateful to the Hubert Bals Fund and the coalition of supremely talented individuals we’ve gathered around this collective effort to step into that gap.”

Interview below is Google translated from Polish to English.

The November weekend was no surprise, it was grey and cold. But behind the walls of Torun’s Old Town, the greys look fabulous. Besides, the International Film Festival of the Art of Cinematography EnergaCAMERIMAGE has started, so you can feel the artistic excitement in the air mixed with the smell of gingerbread. I buy a strong coffee, ask for it to go, and head towards the lobby of the hotel near the Vistula, where I will talk to Cate Blanchett in a moment.

I enter a room as black as coffee. Only two lamps are on, but they are film lamps. I like it. Cate Blanchett, the head of the jury in the Main Competition of this year’s edition of the festival, in a grey suit, greets me warmly, and I hand her Ryszard Kapu?ci?ski’s “The Emperor.” Surprised, she asks about Polish literature. But we’ll come back to that at the end. Before that, I want to know her attitude to acting, the position of women in cinema, and the search for truth and fiction in film.

Is cinema truth or fiction? Or maybe both?

CATE BLANCHETT: I think we constantly fictionalize reality, but we also try to find reality in fiction. And in fact, they are interconnected. Reality tells the truth in a specific way – after all, truth is born from many perspectives. It exists between a dream and an aspiration. Between fiction and a dream. I function in a real space, and when I have the opportunity and the privilege to enter the world of fiction, I use my real experience. So fiction and truth are like a spider’s web, and that is a solid structure.You talk about your own, real-life experiences – so what is your process of preparing for a role? When do you stop acting and let your character speak? How do you create a space that allows you to listen to the character you are constructing?

CB: When I have a new project, I always think to myself, “Gosh, where do I start?” The material you are working with will guide you well. Your collaborators will also have an influence on your preparation, because every cameraman, director, screenwriter has different desires. But none of them – and that is the magic of cinema – can realize them alone. Film is a collective entity, a collective process, and everyone who works on it brings something unique to the table. That is why festivals like the one we are at are so important – because they celebrate the fact that cinema gives the green light to the dreams of filmmakers. To answer briefly, I am very practical when it comes to preparing a role. And because I am a parent, over the years I have shortened all the processes that seemed necessary to me to a minimum.So you approach the act of creation economically.

CB: I don’t have time to think about every detail. I have to sleep. And as strange as it may sound, the best thing an actor can do is simply rest – go for a walk, swim, give yourself a moment of respite. This is when the head processes all the information subconsciously, intuitively. Besides, if you want to create a character with a full plan and awareness from the beginning, after a while it may turn out that you have chosen the wrong path. The simplest advice is infallible: stop thinking about it and analyzing it all the time. It will come. Let the creative process take place naturally.It’s not easy to stop yourself from over-analyzing these days…

CB: And sometimes all it takes is for the cameraman to ask the actor to move four inches to the left. And suddenly everything makes sense. The change of frame becomes this found element that you don’t have to play as an actor anymore. I’ve worked with and still work with great cameramen and I listen to their advice because they’re always right.It takes artistic wisdom to know when to listen and forget about ego for a moment.

CB: I agree. And above all, to know who!As an actress with great charisma and stage presence, you also look for other paths of development in the world of film. This year, during the EnergaCAMERIMAGE festival, you headed the jury of the Main Competition. You took part in the artistic project “Manifesto” by Julian Rosefeldt, exhibited until January 17 at the CSW in Torun. You are the co-founder of the Proof of Concept project, which supports women and minorities in film. You run a production company with your husband, you are an ambassador for the UNHCR. What does this give you?

CB: When you start working with actors on stage, there is an exercise in balancing the space. It’s a bit like a dragonfly seesaw in a playground – the balance only occurs for that one brief moment when the people sitting at the ends of the board have tipped the board correctly. On stage, we look for that moment when everyone can be heard well from certain sides. So in life, I also look for gaps in the space that need to be filled. When I walk onto a film set, I start thinking, “OK, I’m the only woman out of 60 men.” Another set and I see that I’m one of four women, the rest are 37 men. It’s inevitable that over time you start to wonder why this is happening, you become aware that the set has to correspond to reality. Otherwise, how can we create a world in a film if we don’t reflect it in the creative process itself? Over the years, I’ve been lucky to work with many wonderful female cinematographers. Some of my favorite cinematographers are women. I started to wonder how I could amplify their voices.But not just them.

CB: Not just them. I grew up in Sydney, and a lot of my friends are gay, trans, non-binary. Where are their stories? Why aren’t they being told? They are marginalized, yet they are part of society. The life of an artist, which I have the great privilege of living, is not always about talking, but about listening and observing. It is incredibly enriching for me as a person. Selfishly enriching. This year’s jury includes five wonderful cinematographers (Jolanta Dylewska, Anthony Dod Mantle, Rodrigo Prieto, ?ukasz ?al, Anna Higgs – editor’s note) and Sandy Powell (costume designer), with whom I have worked many times. I’m looking forward to hearing their perspectives. Although Rodrigo and I, among others, had already met on set, we were part of a specific project. We didn’t talk about our love for cinema in a global sense. Maybe they could learn something from me, an actress talking about the art of cinematography? In the end, it’s always about the conversation. This is also the case at the UNHCR (since 2016, Cate Blanchett has been a UNHCR Goodwill Ambassador – editor’s note). It is a dialogue with the excluded. Because why should the voices of refugee filmmakers not be heard?The Proof of Concept initiative was born out of questions like these, among others.

CB: Yes, it had the chance to come true thanks in part to a meeting with Dr Stacy L. Smith, who is part of the think tank The Annenberg Inclusion Initiative. When you start studying statistics, you find that the disparities in the film world are staggering. And it’s not us who have gone mad, it’s the world. There are no coincidences here – there are many factors contributing to this and everything must be done to improve it. As a film industry, we have a social responsibility to make an effort to change for the better, for everyone. To give voice and courage to people – women, trans and non-binary people – in other industries. Let us be a good example of change that will carry on. Others will follow in our footsteps. This is especially important now, at a turning point in human history.As I was preparing for our conversation, an internet search engine showed me one of your quotes completely out of context: “I’m this weird creature who really likes wearing corsets.” Until recently, corsets were an afterimage of the oppression of women, but recently something has started to change. We talk about them in terms of power. In your case, as an actress who takes on historical roles, like Elizabeth I in Shekhar Kapur’s film, a corset can be a confidence booster…

CB: Exactly, because I like wearing corsets as an actress. No one forces me to wear them every day. I don’t have to cover anything or restrict my body. I don’t have a specific outfit imposed on me. This brings us back to your first question – the difference between fantasy and reality. It’s about what a corset does to my posture, my stage presence. The way I stand, move, affects the energy that the character radiates, which is why this piece of clothing often helps in my work. It shapes the character. But if someone told me to wear a corset in real life, I wouldn’t like it. Quotes without context completely change the reception of the message.And it is increasingly said that corsets actually help to breathe, as well as to maintain a commanding posture, boosting self-confidence.

CB: That is why opera singers often wear special constructions that are a support for the diaphragm so they can take deeper breaths.What if I asked you metaphorically, what kind of corset are women in cinema wearing today? Have those corsets been thrown off?

CB: The very fact that we have to talk about it signals a problem. I don’t know about you, but in a professional context, I don’t think about my gender until it’s brought up in a conversation. And putting it that way kind of narrows the discussion. There are as many amazing female artists as there are male artists. It’s only men in cinema that aren’t a topic – for a simple reason – there are so many men in cinema. And I feel proud to be a woman in film from the perspective that I represent and my female colleagues – excellent female artists. I just don’t want the term ‘women in cinema’ to become a label that will forever limit us. We have to be careful not to fall into the trap of self-ghettoization. I remember when my husband (Andrew Upton, screenwriter – editor’s note) and I were running the National Theatre in Australia, we kept saying that a common mistake is to pair a novice playwright with a novice director. And you have to do it differently – pair a young playwright with one of the most experienced directors, so that the director can refresh his or her perspective with a newcomer. And the young playwright could benefit from experience. And such mixing of perspectives is, in my opinion, the key to breaking patterns and searching for the new. We talk about women’s metaphorical corsets, but men wear them too.The crisis of masculinity is increasingly being talked about in the public sphere.

CB: Because when a diversity of perspectives doesn’t come to the table, it only leads to limitations. Besides, it’s boring. Regardless of gender. And for men, it means that they will continue to revolve around the same expectations.Or is it because this discussion started too late? In the visual arts, the voices of female painters such as Frida Kahlo or Hilma af Klint were heard only in the 1970s, and Linda Nochlin wrote a famous essay at the time, “Why There Were No Great Women Artists,” which is still relevant today.

CB: That, too.So speaking of artists, let’s touch on the musical context. You played Lydia Tar, the conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, in the film “Tar”. And it wasn’t the first time you played a musician. Previously, you played Bob Dylan in the film “I’m Not There” directed by Todd Haynes. You use accents very well, as we recently heard in “Rumours” by Guy Maddin and Evan Johnson. How important is the world of music and sounds to you? Are you sensitive to them?

Oh yes. Working with Todd Haynes is extraordinary, because he always has a soundtrack prepared for each character and for the whole picture. This is important, because we can often spend a long time looking for common points, connections between characters. Sometimes the imagery helps. When we were preparing “Carol” (directed by Todd Haynes – editor’s note), we talked a lot about the photography of Vivian Maier and Saul Leiter. It was wonderful working with Todd and Ed [Edward Lachman, cinematographer – ed.] But for me, the trigger is usually a song, a phrase, a sound or a musical landscape that will allow the material to connect in a subtle, profound way. That’s why I often prepare my own playlists for roles.That’s why I’ll ask you about your role at the end. We started our meeting by talking about Polish writers, so I’ll quote a fragment of a poem by the Nobel Prize winner Wislawa Szymborska, “Life on the Wait”: “I don’t know the role I’m playing / I only know that it’s mine, unchangeable.” Have you thought about your role in life today?

CB: Of course. I think about it, because life is unpredictable and often you can simply not reach your destination. That’s why I’m quite careful not to fall into the trap of fixed roles, in which it’s easy to lose yourself. Then I shake myself. Lately, however, I’ve been thinking a lot about being as quiet as possible, because the world has become unbearably loud. And there are so many voices in it that haven’t been heard for generations. That’s why I need my silence – to hear them all. Usually, you pay attention to the loudest person in the room. I want to find the one who speaks the least and give them a voice. At the moment, that’s my role – to listen, to look, to absorb.

Sources: IFFR, Elle Polska

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?)

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?) The Seagull (2025)

The Seagull (2025) Bozo Over Roses (2025)

Bozo Over Roses (2025) Black Bag (2025)

Black Bag (2025)  Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)

Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)  Disclaimer (2024)

Disclaimer (2024)  Rumours (2024)

Rumours (2024)  Borderlands (2024)

Borderlands (2024)  The New Boy (2023)

The New Boy (2023)

Thank you for sharing this amazing initiative! The Displacement Film Fund is such a powerful way to support displaced filmmakers and amplify their authentic voices. It’s inspiring to see such meaningful collaboration to bring these important stories to the forefront. Excited to see the impact this will have!